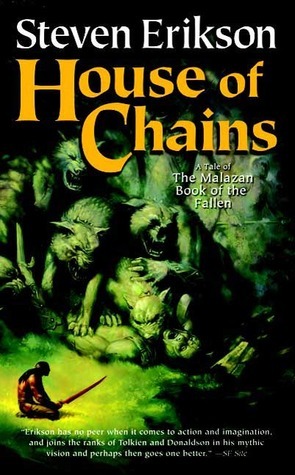

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The sea had been born of a river on another realm. A massive, wide and probably continent-spanning artery of fresh water, heavy with a plain’s silts, the murky depths home to huge catfish and wagon-wheeled-sized spiders, its shallows crowded with the crabs and carnivorous, rootless plants. The river had poured its torrential volume onto this vast, level landscape. Days, then weeks, then months. Storms, conjured by the volatile clash of tropical air-streams with the resident temperate climate, had driven the flood on beneath shrieking winds, and before the inexorably rising waters came deadly

...more

Among his people, it was a long-known truth, perhaps the only truth, that Nature fought but one eternal war. One foe. That, further, to understand this was to understand the world. Every world. Nature has but one enemy. And that is imbalance.

Drowning was common among his people. Drowning was not feared. And so, Trull Sengar would drown. Soon. And before long, he suspected, his entire people would join him. His brother had shattered the balance. And Nature shall not abide.

Moving silent and unseen through enemy camps, shifting the hearthstones to deliver deepest insult, eluding the hunters and trackers day and night until the borderlands were reached, then crossed—the vista ahead unknown, its riches not even yet dreamed of.

Seven figures rose from the ground,

When failure was honourable, their sentient remnants would be placed open to the sky, to vistas, to the outside world, so that they might find peace in watching the passing of eons. But, for these seven, failure had not been honourable. Thus, the darkness of a tomb had been their sentence. They had felt no bitterness at that.

Their kin had marked this place of internment, with carved faces each a likeness, mocking the vista with blank, blind eyes. They had spoken their names to close the ritual of binding, names that lingered in this place with a power sufficient to twist the minds of the shamans of the people who had found refuge in these mountains, and on the plateau with the ancient name of Laederon. The seven were silent and motionless in the

‘You place too much faith in these fallen Teblor. Teblor. They know naught, even their true name.’ ‘Be glad that they do not,’ said Ber’ok, his voice a rough rasp through a crushed throat. Neck twisted and head leaning to one side, he was forced to turn his entire body to stare at the rock-face. ‘In any case, you have your own children, Sin’b’alle, who are the bearers of the truth. For the others, lost history is best left lost, for our purposes. Their ignorance is our greatest weapon.’

‘We could not have so twisted their faith were they cognizant of their legacy.’

Sundering the Vow stole much of our power—’ ‘Yet what has our new master given of his, Antler From Summer?’ Thek Ist demanded. ‘Naught but a trickle.’ ‘And what do you expect?’ Urual enquired in a quiet tone. ‘He recovers from his ordeals as we do from ours.’

The seven figures returned to the earth as the first stars of night blinked awake in the sky overhead. Blinked awake, and looked down upon a glade where no gods dwelt. Where no gods had ever dwelt.

Teblor horse-trappings did not include a rider’s seat; a warrior rode against flesh, stirrups high, the bulk of his weight directly behind the mount’s shoulders. Lowlander trophies included saddles, which revealed, when positioned on the smaller lowlander horses, a clear shifting of weight to the back. But a true destrier needed its hindquarters free of extra weight, to ensure the swiftness of its kicks. More, a warrior must needs protect his mount’s neck and head, with sword and, if necessary, vambraced forearms.

Winter arrived and departed with violent storms high in the mountains, the savage exertions of the spirits in their eternal, mutual war. Summer and winter were as one: motionless and dry, but the former revealed exhaustion while the latter evinced an icy, fragile peace.

Accordingly, the Teblor viewed summers with sympathy for the battle-weary spirits, while they detested winters for the weakness of the ascendant combatants, for there was no value in the illusion of peace.

There would be no fire, so they ate the rabbits Delum had caught raw. Once, such fare would have been risky, for rabbits often carried diseases that could only be killed by cooking, most of them fatal to the Teblor. But since the coming of the Faces in the Rock, illnesses had vanished among the tribes. Madness, it was true, still plagued them, but this had nothing to do with what was eaten or drunk.

The blade’s wood was deep red, almost black, the glassy polish making the painted warcrest seem to float a finger’s width above the surface. The weapon’s edge was almost translucent, where the blood-oil rubbed into the grain had hardened, coming to replace the wood. There were no nicks or notches along the edge, only a slight rippling of the line where damage had repaired itself, for blood-oil clung to its memory and would little tolerate denting or scarring.

blood-oil

‘This valley runs into others that all lead northward, all the way to the Buryd Fissure. Pahlk was among the Teblor elders who gathered there sixty years ago. The river of ice filling the Fissure had died, suddenly, and had begun to melt.’

The river had a black heart, or so its death revealed, but whatever lay within that heart was either gone or destroyed. Even so, there were signs of an ancient battle in that place. The bones of children. Weapons of stone, all broken.’

Our blood was cloudy and would grow cloudier still. I saw the need to shatter what remained. For the T’lan Imass were still close and much agitated and inclined to continue their indiscriminate slaughter.”’ Karsa scowled. ‘T’lan Imass? I do not know those two words.’

And so I sundered husband from wife. Child from parent. Brother from sister. I fashioned new families and then sent them away. Each to a different place.

The Laws of Isolation would be our salvation, clearing the blood and strengthening our children.

Shrugging, Karsa returned his attention to the stone wall. ‘“To survive, we must forget. So Icarium told us. Those things that we had come to, those things that softened us. We must abandon them. We must dismantle our…” I know not that word, “and shatter each and every stone, leaving no evidence of what we had been.

Behind them, Gnaw stood beside the cairn a moment longer. The sun had left the wall, filling the cave with shadows. In the darkness, the dog’s eyes flickered.

‘And this is what troubles me, Karsa Orlong. Those legends and their tales of glory—they describe an age little different from our own. Aye, more heroes, greater deeds, but essentially the same, in the manner of how we lived. Indeed, it often seems that the very point of those tales is one of instruction, a code of behaviour, the proper way of being a Teblor.’

Bairoth nodded. ‘And there, in those carved words in the cave, we are offered the explanation.’ ‘A description of how we would be,’ Delum added. ‘No, of how we are.’

‘We were a defeated people,’ Delum continued, as if he hadn’t heard. ‘Reduce...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

‘The fallen know but one challenge,’ Karsa resumed. ‘And that is to rise once more. The Teblor were once few, once defeated. So be it. We are no longer few. Nor have we known defeat since that time.

Who from the lowlands dares venture into our territories?” Karsa Orlong, we travel an empty valley. Empty of Teblor, aye. But what has driven them away? It may be that defeat stalks the formidable Teblor once more.’

here and there, among the stone foundations of the circular houses, the signs of fire and violence could be seen.

The hand, Karsa could see, was neither Teblor nor lowlander, but in size somewhere in between, the bones prominent, the fingers narrow and overlong and seeming to bear far too many joints.

‘The Spirit Wars were two, perhaps three invasions, and had little to do with the Teblor. Foreign gods and demons. Their battles shook the mountains, and then but one force remained—’

The hand trapped beneath that body had clawed out a space for itself first, then had slowly worked grooves for hip and shoulder. Both feet, which were bare, had managed something similar.

Elongated limbs, extra-jointed, the skin stretched taut and pallid as moonlight. A mass of blue-black hair spread out from the face-down head, like fine roots, forming a latticework across the stone floor. The demon was naked, and female.

Bairoth moved to take her weight but Karsa snapped a hand out to restrain him. ‘No, Bairoth Gild, she has known enough pressure that was not her own. I do not think she would be touched, not for a long time, perhaps never again.’ Bairoth’s hooded gaze fixed on Karsa for a long moment, then he sighed and said, ‘Karsa Orlong, I hear wisdom in your words. Again and again, you surprise me—no, I did not mean to insult. I am dragged towards admiration—leave me my edged words.’

She mocks her own sorry condition. This, her first emotion upon being freed. Embarrassment, yet finding the humour within it.

Karsa now saw that some of the dustiness was gone from her eyes, and that her lips were now slightly fuller. ‘She recovers,’ he said. ‘Freedom was all she needed,’ Bairoth said. ‘In the manner that sun-hardened lichen softens in the night,’ Karsa said. ‘Her thirst is quenched by the air itself—’

‘They will not leave you, will they? These once enemies of mine. It seems shattering their bones was not enough.’ Something in her eyes softened slightly. ‘Your kind deserve better.’ The face slowly withdrew. ‘I believe I must needs wait. Wait and see what comes of you, before I decide whether I shall deliver unto you, Warrior, my eternal

peace.’

‘Warleader, I did not draw my weapon. I did not seek to protect you as did Delum Thord—’ ‘Which leaves one of us healthy,’

Slanting crossways across his forehead were four deep impressions, the skin split, yellowy liquid oozing from the punched-through bone underneath. Her fingertips. Delum’s eyes were wide, yet cloudy with confusion. Whole sections of his face had gone slack, as if no underlying thought could hold them to an expression.

Come, we must wrap Delum’s wounds. The thought-blood will gather in the bandages and dry, and so clot the holes. Perhaps it will not leak so much then and he will come some of the way back to us.’ The two warriors set off for their camp. When they arrived they found the dogs huddled together, racked with shivering. Through the centre of the clearing ran the tracks of Calm’s feet. Heading south.

The three Teblor were as children before her. Delum should have seen that, instantly, should have stayed his hand as Bairoth had done. Instead, the warrior had been foolish, and now he crawled among the dogs. The Faces in the Rock held no pity for foolish warriors, so why should Karsa Orlong? Bairoth Gild was indulging himself, making regret and pity and castigation into sweet nectars, leaving him to wander like a tortured drunk.

The air sparkled strangely before them, then coruscating fire suddenly unfolded, swept forward to engulf Karsa. It raged against him, a thousand clawed hands, tearing, raking, battering his body, his face and his eyes. Karsa, shoulders hunching, walked through it. The fire burst apart, flames fleeing into the night air. Shrugging the effects off with a soft growl, Karsa approached the four lowlanders.

‘Karsa Orlong,’ Bairoth had to shout to be heard over the roar rising from far below, ‘someone—an ancient god, perhaps—has broken a mountain in half. That notch, it was not carved by water. No, it has the look of having been cut by a giant axe. And the wound…bleeds.’

The bones were lowlander in scale, yet heavier and thicker, hardened into stone. Here and there, antlers and tusks were visible, as well as artfully carved bone helms from larger beasts. An army had been slain, their bones then laid out, intricately fashioned into these grim steps. The mists had quickly laid down a layer of water, but each step was solid, broad and slightly angled back, the pitch reducing the risk of slipping.

Pale, ghostly light broken by shreds of darker, opaque mists commanded the ledge that spread out on this side of the waterfall. The bones formed a level floor of sorts, abutting the rock wall to the right and appearing to continue on beneath the river that now roared, massive and monstrous, less than twenty paces away on their left.

The faint glow emanating from the bones seemed to carry a breath unnaturally cold. On all sides, the scene was colourless, strangely dead. Even the river’s immense power felt lifeless.

There were always dogs on lowlander farms, kept for the same reason as Teblor kept dogs. Sharp ears and sensitive noses, quick to announce strangers. But these would be lowlander breeds—smaller than those of the Teblor. Gnaw and his pack would make short work of them.

No lowlander horse could clear this wall, but Havok stood at twenty-six hands—almost twice the height and mass of the lowlander breeds—and, muscles bunching, legs gathering, the huge destrier leapt, sailing over the wall effortlessly.