More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Marthe Cohn

Read between

January 12 - February 6, 2020

“Each of our deeds, even those as small as the flapping of a butterfly’s wings, has great consequences.”

my salvation was reading.

I was never happier than lying on my belly in the large bay window of the lounge of my parents’ apartment, hiding behind the thick curtains, lost in a book.

My grandfather was my strongest influence as far as education was concerned.

“People are intolerant because they are frightened by what they don’t understand or deem different,” he told me. “You must never judge a person by his religion, skin color, or beliefs. If someone needs help, you never ask his or her race or creed, you just give it. And you never boast about what you’ve done, or it would humiliate the person you’ve helped.”

He and Fred were my true role models.

Just turned twenty, I came to understand that despite all my earlier optimism, our lives had been changed irrevocably. Nothing was certain anymore.

General de Gaulle, who’d rallied the Free French around the world from London and become a symbol of liberation, was sentenced to death in his absence.

I realized she was an iron hand in a velvet glove.

“But Maman,” I said, my eyes filling with tears of pride, “how on earth did you make yourself understood in Paris? You surely didn’t speak German?” “No, Marthe,” she said, a twinkle in her eye. “I spoke French.”

Seeing our confused reactions, she smiled. “I’m afraid, my darlings, that I’ve been able to speak it for years. I just didn’t want you knowing or you’d stop ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

And so on, along the row, men and women, desperately poor, urgently in need of the money they could so easily have earned from us as a reward, each one saying a prayer to guide us on our way.

I could hardly believe my eyes. It was so beautiful, the humanity of it. Tears rolled down my cheeks as I nodded my head in silent thanks to each and every one we passed. How could I, even for the shortest minute, have doubted them, these kind, simple people

who were as much oppressed by the Nazis as we were? Lowering my head, I pressed on, taking my mother and grandmother to unoccu...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I barely ate or slept, and sat up reading most of the night. Reading had always been my salvation, the only activity that permitted me to forget my tribulations, although several of the chapters had to be read over and over again before I could begin to take them in. The words just merged on the page.

There would never be another like him.

They were nothing to them—just a handful among thousands of brave Resistance members tortured and killed for their beliefs—their bodies tossed into graves like so much discarded rubbish.

There was an extraordinary network of people ready to help those in danger.

We didn’t dare stay anywhere too long,

You can be a hero one day and a coward the next. I know. I’ve been both.

The Germans were everywhere. They’d taken over all the best mansions and hotels, and were in the restaurants, cinemas, and theaters every night. There was no avoiding them.

“We’re not allowed to enlist Jews.” I backed away in horror. It wasn’t the first time I was disappointed by the international organization that prided itself on being neutral.

The Americans, who’d led the way until now, had allowed them the courtesy of entering Paris first. I was just back from work and home with Cecile when we heard the momentous news.

Now, after four dark years of German occupation, we were singing directly at the enemy soldiers, some of whom lifted their guns and pointed them at us. They didn’t shoot; they were too terrified at the overwhelming reaction all around them. We’d endured their presence until now, avoided them as best we could, lived with their rules and coped with hunger and privations. But the tables had turned. This was their last breath in Paris and they knew it. Only the curfew prevented us from running into the streets and dancing, but as the bells continued to ring out, we were still able to show them how

...more

De Gaulle announced: “I wish simply to say from the bottom of my heart: ‘Vive Paris!’

I wanted to see what was going on, to be a part of history. It’s very rare that you live through a moment of history like that.

The next day the Americans would arrive, in even greater numbers, but the first twenty-four hours it was only French soldiers being welcomed and thanked so profusely. Old men dusted off their best suits, women unpacked the Liberation Day dresses they’d been storing for four years, and barmen popped open their hidden bottles of champagne.

The elation that had first overwhelmed me became tempered with guilt at having survived.

The closer they got to their Fatherland, the fiercer they fought, for fear of what the Allies might do to their homes and families in retribution for what the Germans had done to theirs.

With those letters written and my training complete, I felt ready to begin, as Hitler’s crucial counteroffensive, the Battle of the Bulge, was being successfully repelled in the Ardennes a few hundred miles north.

To take pressure off the German troops in the Battle of the Bulge, in which 600,000 U.S. and Allied troops had only just managed to halt the massive German counteroffensive in Belgium, the enemy had launched Operation Nordwind to try and trap seven American divisions along the Rhine and recapture Strasbourg. The Germans were halted at the last bridge short of the city and were now slowly retreating. “Firsthand intelligence is urgently required,” the captain told me. “They’re fighting fiercely. We need you to report back to us as often as possible, and follow the retreating Germans as you do

...more

It’s a highly sensitive mission.”

In that moment I realized that courage or cowardice depends entirely on circumstance and one’s state of mind.

see

There was a new expression on the faces of most of the ordinary Germans I met. It was panic.

I was relieved to still be alive, and glad that I’d done something meaningful to help. But inside, I was tormented by guilt at having survived.

The rest were immediately gassed—just a handful of the two million people whose lives were extinguished at Auschwitz.

Of those who survived, many were treated with the utmost cruelty. Pregnant women were beaten and kicked to death, newborn babies slaughtered, young women bled dry by an army in desperate need of transfusions for its wounded soldiers at the front. By the end of the war, only twenty-three

of that original convoy of 1,157 men, women, and children were still alive. In total, only 2,500 of the Jews deported fr...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

When pressed, one—a cousin of Rosette—told us only: “She’s dead. That’s all you need to know.” We can only imagine the worst.

My decision to leave Germany was also based on my fear that I was getting too much of a swollen head. Power is a strange commodity, and I wasn’t sure I handled it terribly well.

In January 14, 1946, I finally applied to leave. My life as the unlikeliest of spies was over.

Once peace came, we were to travel the world and work in medicine, alleviating instead of inflicting pain and suffering.

To have survived the war as a Jew was good enough; but I felt that to continue the family line, for the sake of Grospapa and my parents, was the most important aspect of my survival.

I have found my lost “son.”

Despite all that we went through, the years of daily terrors, none of us ever really lost hope.

War taught me many things, among them that, like anyone, I could be a coward one minute and brave the next, depending entirely on circumstance. They say that war brings out the best and the worst in people, and I certainly saw both sides. When I think of the dozens of people who risked their lives for us, it almost helps compensate for all the sad and bitter memories of those who were so cruel. War also made me accept the inevitable and savor the important gains, like my two wonderful sons and the granddaughter I might so easily have never lived to see. Through the memories of those we’ve lost

...more

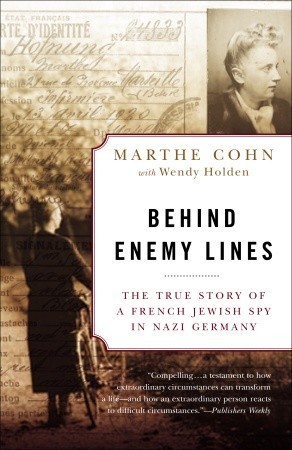

Marthe Cohn, at the age of eighty, was awarded France’s highest military honors. It was the first time her children and grandchildren had even heard of her exploits. She lives in Palo Verdes, California.