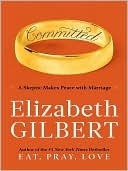

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

“And what do you believe is the secret to a happy marriage?” I asked earnestly.

Now they all really did lose it. Even the grandmother was openly howling with laughter. Which was fine, right? As has already been established, I am always perfectly willing to be mocked in a foreign country for somebody else’s entertainment. But in this case, I must confess, all the hilarity was a bit unsettling on account of the fact that I really did not get the joke. All I could understand was that these Hmong

In the modern industrialized Western world, where I come from, the person whom you choose to marry is perhaps the single most vivid representation of your own personality. Your spouse becomes the most gleaming possible mirror through which your emotional individualism is reflected back to the world. There is no choice more intensely personal, after all, than whom you choose to marry; that choice tells us, to a large extent, who you are.

My friend Kate once went to a concert of Mongolian throat singers who were traveling through New York City on a rare world tour. Although she couldn’t understand the words to their songs, she found the music almost unbearably sad. After the concert, Kate approached the lead Mongolian singer and asked,

“What are your songs about?” He replied, “Our songs

When we speak today, then, about “holy wedded matrimony,” or the “sanctity of marriage,” we would do well to remember that, for approximately ten centuries, Christianity itself did not see marriage as being either holy or sanctified.

Marriage was certainly not modeled as the ideal state of moral being.

As just one example: A great wave of matrimonial fever swept across medieval Europe right after the Black Death had killed off seventy-five million people. For the survivors, there were suddenly unprecedented avenues for social advancement through marriage. After all, there were thousands of brand-new widows and widowers floating around Europe with a considerable amount of valuable property waiting to be redistributed, and perhaps no more living heirs. What followed, then, was a kind of matrimonial gold rush, a land grab of the highest order.

In medieval Germany, the courts even went so far as to create two different kinds of legal marriage: Muntehe, a heavily binding permanent life contract, and Friedelehe, which basically translates as “marriage-lite”—a more casual living arrangement between two consenting adults which took no account whatsoever of dowry requirements or inheritance law, and which could be dissolved by either party at any time.

By the thirteenth century, though, all that looseness was about to change because the church got involved in the business of matrimony again—or rather, for the first time.

In the year 1215, then, the church took control of matrimony forever, laying down rigid new edicts about what would henceforth constitute legitimate marriage. Before 1215, a spoken vow between two consenting adults had always been considered contract enough in the eyes of the law, but the church now insisted that this was unacceptable. The new dogma declared: “We absolutely prohibit clandestine marriages.” (Translation: We absolutely prohibit any marriage that takes

place behind our backs.)

Just to further tighten controls, Pope Innocent III now forbade divorce under any circumstances—except in cases of church-sanctioned annulments, which were often used as tools of empire building or empire busting.

Moreover, the church’s strict new prohibitions against divorce turned marriage into a life sentence—something it had never really been before, not even in ancient Hebrew society.

To further enforce controls over wealth management and stabilization, courts all across Europe were now seriously upholding the legal notion of coverture—that is, the belief that a woman’s individual civil existence is erased the moment she marries.

wife effectively becomes “covered” by her husband and no longer has any legal rights of her own, nor can she hold any personal property.

My aversion is not entirely irrational either. The legacy of coverture lingered in Western civilization for many more centuries than it ought to have, clinging to life in the margins of dusty old law books, and always linked to conservative assumptions about the proper role of a wife. It wasn’t until the year 1975, for instance, that the married women of Connecticut—including my own mother—were legally allowed to take out loans or open checking accounts without the written permission of their husbands. It wasn’t until 1984 that the state of New York overturned an ugly legal notion called “the

...more

In 1907, a law was passed by the United States Congress stating that any natural-born American woman who married a foreign-born

born man would have to surrender her American citizenship upon her marriage and automatically become a citizen of her husband’s nation—whether she wanted to or not.

in the American matrimonial saga was a fellow named Paul Popenoe, an avocado farmer from California who opened a eugenics clinic in Los Angeles in the 1930s called

Popenoe, the father of American eugenics, also went on to launch the famous Ladies’ Home Journal column “Can This Marriage Be Saved?” His intention with the advice column was identical to that of the counseling center:

Charles Benedict Davenport was the "father" of eugenics in the U.S.; he was a professor at Harvard (and a graduate of the same).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6736015/

Paul Popenoe was not the "father" of American eugenics but that of marriage counseling in the U.S.: "In 1930, he founded a counseling center, the American Institute of Family Relations in Los Angeles, which the media referred to as “the Mayo Clinic of family problems.”

https://timeline.com/popenoe-eugenics-marriage-counseling-faa8aacb0f3d

Popenoe followed and read about Germany's various counseling therapies to incorporate in his practice and was an admirer of Hitler's eguenics practices.