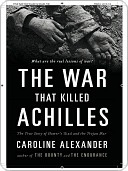

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Is a warrior ever justified in challenging his commander? Must he sacrifice his life for someone else’s cause? How is a catastrophic war ever allowed to start— and why, if all parties wish it over, can it not be ended? Giving his life for his country, does a man betray his family? Do the gods countenance war’s slaughter? Is a warrior’s death compensated by his glory? These are the questions that pervade the Iliad.

Elsewhere, Zeus similarly threatens other gods; the point of the scene with Hera is not that he is an abusive husband but that there exists no agency that can stand up to his might.

In the rebellion of Achilles, two powerful thematic lines have converged, one historical, one mythic: the historic reas- sessment of an individual’s unquestioned duty to his ruler and the playing out of Achilles’ inherently subversive destiny.

Bound by tribal and familial bonds of unyielding if resentful loyalty, the whole of Troy is engulfed in a war fought for what is universally acknowledged as a wrongful, hateful cause.

as will be seen, heroism is achieved by striving in the face of unconquerable destiny.

the Iliad consistently, if sympathetically, portrays Helen as the remorseful agent of her own disastrous decision.

the Iliad ensures that the enemy is humanized and that the deaths of enemy Trojans are depicted as lamentable. The Iliad is insistent on keeping to the fore the price of glory.

Again and again, relentlessly, the Iliad hammers this fact: The death of any warrior is tragic and full of horror. Even in war, death is regrettable.

There has been no evidence to this point in the epic that heroes fight for anything as insubstantial as glory.

Achilles, moreover, not only rejects the Embassy but, as will be seen, goes further, challenging the very premise of the heroic way of life, which is to say the heroic way of war that epic traditionally extols.

As important, he is also Achilles’ phílos hetaros, his own, his dear, his beloved companion.

Also manifest within his stern, thrice-repeated injunctions are his deepest fears—that he lose honor, that Patroklos not return to him alive.

Phílos; hetaros—“comrade,” “buddy,” “mate”—“my own,” “my best,” “my beloved companion.” The terms that define the relationship between Patroklos and Achilles have no true counterparts in the civilian world but belong to the enduring terminology of war.

Achilles the warrior was once gallant and chivalrous; since the death of Patroklos, he is a different, murderous man.

Would that my passion and spirit would drive me to devour your hacked-off flesh raw, such things you have done; so there is no one who can keep the dogs from your head,

I shall not forget him as long as I am among the living and my own knees have power in them. And if men forget the dead in Hades, I will remember my beloved companion even there.

Achilles demonstrates profound knowledge of the disposition of men’s souls, including his own.

It is not, after all, for glory that he sacrifices his life, but for Patroklos.