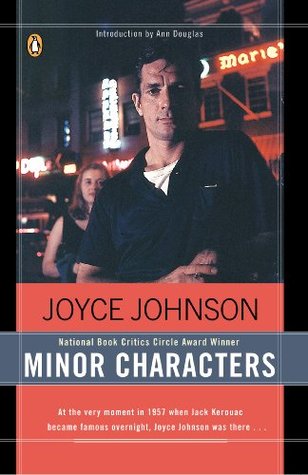

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I long to turn myself into a Bohemian, but lack the proper clothes.

My idea of the life that would await me in college was a composite of images from three main sources: the works of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Mademoiselle magazine, and the campus department of Lord and Taylor.

There is a winter night that from this distance looks inevitable.

I READ THE WORDS Beat Generation for the first time sitting in my parents’ living room. It was November 16, 1952.

On this particular Sunday, an article by a writer named John Clellon Holmes immediately caught my attention. Entitled “This Is the Beat Generation,” it was a declaration of faith in a state of mind that, although new, according to this article, was totally familiar to me:

“Everyone I knew,” Holmes wrote, “felt it in one way or another — that bottled eagerness for talk, for joy, for excitement, for sensation, for new truths. Whatever the reason, everyone of my age had a look of impatience and expectation in his eyes that bespoke ungiven love, unreleased ecstasy and the presence of buried worlds within.”

But wasn’t this “bottled eagerness” exactly what we felt? Could we be somehow more a part of the Beat Generation than of the Silent one we’d been born into chronologically?

That strangely used word Beat was immediately arresting. For one thing, it was blatantly ungrammatical.

The people Holmes described were in fact beaten down — down to “the bedrock of consciousness,” achieving a desperate beauty that seemed to be a kind of triumph. Holmes did not take credit for coining the phrase; with great scrupulousness he attributed it to a fellow writer and hipster named Jack Kerouac.

There are books that serve as mirrors in which one catches reflections of oneself.

Alone on the mountain, with the laconic crackling voices that came over the fire lookout’s radio as disembodied human contacts, Jack was prepared to grapple once and for all with the sense of mortality that overwhelmed him periodically, the awful knowledge we’re-all-gonna-die which could be crowded out by movement or sex or wine or the frantic conviviality of poets and intellectuals in cities or by his own huge efforts to remember, to get it all down lest it vanish without a trace —

There was a photo of Allen with three other men, a cherubic hoodlum named Gregory Corso, a scholarly Philip Whalen, and a writer who had a crucifix around his neck and tangled black hair plastered against his forehead as if he’d just walked out of the rain. He looked wild and sad in a way that didn’t seem appropriate to the occasion. This was Jack Kerouac, whose reputation was underground.

I remembered the man with the dark, anguished face and the name that was unlike anyone else’s, the harsh music of its three syllables. Soon afterward I found it on a book at the office. A battered copy of The Town and the City was on a shelf where they put things that weren’t active any more. I

It was as if the power of Jack’s imagination always left him defense-less. He forgot things anyone else would have remembered.

Interestingly enough, the only woman Jack Kerouac ever actually took with him on the road wasn’t me or Edie Parker or Carolyn Cassady or any of the dark fellaheen beauties of his longings, but Gabrielle L’Evesque Kerouac, age sixty-two, with her bun of iron-grey hair and her round spectacles and her rosary beads in her old black purse.

Legend adheres to artists whose deaths seem the corollaries of their works.

In one biography it was later said, “Lucien called Joyce ’Ecstasy Pie’ and her affair with Jack would endure for an erratic year and a half,” which, aside from obliterating the historic actual pie, allows for no nuances whatsoever.