More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

December 8 - December 13, 2024

The crucial figure in common to all these elections was Richard Nixon—the brilliant and tormented man struggling to forge a public language that promised mastery of the strange new angers, anxieties, and resentments wracking the nation in the 1960s.

Millions of Americans recognized the balance of forces in the exact same way—that America was engulfed in a pitched battle between the forces of darkness and the forces of light. The only thing was: Americans disagreed radically over which side was which.

“Iowa would go Democrat when hell went Methodist.”

The troopers rushed, clubs flailing, tear-gas canisters exploding, white spectators wildly cheering them on; then Jim Clark’s forces, on horseback, swinging rubber tubes wrapped in barbed wire, and bullwhips, and electric cattle prods, littered the bridge with writhing black bodies splattering blood. The film ran on national TV. Over and over. On NBC, the broadcast cut into a showing of the film Judgment at Nuremberg—a story about what happens when ordinary citizens turn a blind eye to evil.

Federal mediators negotiated safe passage for a peaceful march a week later. The next night, local thugs beat the Reverend James Reeb, a white minister from Boston, to death (he had been watching Judgment at Nuremberg when his conscience directed him to travel to Selma).

“It is wrong—deadly wrong—to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country…. There is no issue of states’ rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights…. Their cause must be our cause, too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.”

The Washington Post editorialized of a party fighting off an “attempted gigantic political kidnapping” by “fanatics”: a party in smoldering ruins, ghouls the only sign of life.

That didn’t keep the patriarch from affecting a peacocklike sense of superiority. To the point of tedium, he would remind people that he had once met William McKinley—as if that, and not the family he was raising, was his life’s great accomplishment.

Richard Nixon was a serial collector of resentments. He raged for what he could not have or control.

He contained his raging ambition in the discipline of debate. That was his father’s influence; the surest way to Frank’s heart (though there was never really any sure way) was through skill at argumentation. Frank loved to argue, sometimes to the point of driving customers from the store. The son received his first opportunity to argue competitively in the fifth grade, and his father, the sixth-grade dropout, did the research, obsessed with seeing his son whip others with words. When Dick joined the high school debate team, Frank attended every meet. Dick won often. The coach bemoaned his

...more

But Nixon always had a gift for looking under social surfaces to see and exploit the subterranean truths that roiled underneath.

Being hated by the right people was no impediment to political success. The unpolished, after all, were everywhere in the majority.

Martyrs who were not really martyrs, oppressors who were not really oppressors: a class politics for the white middle class.

And in the navy, Richard Nixon played poker. That’s not how he would later put it, running for Congress in 1946 on a made-up record of time spent “in the foxholes.”

On Green Island, Nixon set up Nick’s, a makeshift beer joint where between more hazardous duty combatants dropped in for games of high-stakes poker.

At any rate he won enough money at poker to fund the greater part of his first congressional race.

Hannah would come to recast Richard in her mind as an impregnable figure of destiny, bringer of miracles. When he became famous, she began to report that Richard had been born the day of an eclipse (he wasn’t), that his ragged and forlorn family had sold land upon which oil was found immediately afterward (they hadn’t). The exaggerations she got away with drove home for her son the lesson that a lie unexposed does no harm, that a soul viewed as a saint can also lie. And her swooning (though she withheld praise in his presence) drove home a lesson the politician was predisposed to internalize:

...more

If nobility was Jerry Voorhis’s liability, nobody had thought to exploit it before.

You didn’t have to attack to attack. Better, much better, to give something to the mark: make him feel that he has one up on you. Let him pounce on your “mistake.” That makes him look unduly aggressive. Then you sprang the trap, garnering the pity by making the enemy look like a self-righteous and hyperintellectual enemy of common sense. You attacked jujitsu-style, positioning yourself as the attacked, inspiring a strange sort of protective love among voters whose wounded resentments grow alongside your performance of being wounded.

It was part of the method: challenged on the lie, he attacked the challenger, in tones of self-pity, for lying. Even if he had to lie to do it:

The House Un-American Activities Committee maneuvered, characteristically, to steal the limelight, calling hearings on espionage to piggyback on a New York grand jury’s recent indictment of twelve Communist leaders based on the testimony of Elizabeth Bentley, whom the New York World-Telegram racily labeled a “beautiful blonde.” She was actually a homely brunette. But a sense of sexualized menace was a common currency of voyeuristic tabloids and voyeuristic congressional committees at the high tide of the Cold War.

He had ascertained a change in the cultural winds. Once the faith of boobs, Red-hunting was now the state religion. In the Hiss case, Nixon spotted the chance to engineer his investiture as its pope.

Here was someone who had everything Nixon coveted: the Harvard pedigree, the affection of Supreme Court justices—“tall, elegant, handsome, and perfectly poised” to boot, Nixon recalled some thirty years after the fact. Here was someone he could hate quite productively.

For Richard Nixon the bottom line was this: he had beaten the Franklins, and for this the bastards would never forgive him. So, proactively, he would never forgive them.

Large tracts of Joseph McCarthy’s speech were borrowed outright from Nixon’s peroration. The pitch Nixon had spent years setting up, McCarthy hit out of the park. The bastard.

George Smathers beat Florida senator Claude Pepper by accusing him of being a “sexagenarian,” committing “nepotism” with his sister-in-law, openly proud of a sister who Smathers said was a “thespian.”

“Pink right down to her underwear,”

The explanations were complicated. The smear was simple.

This was not the time for nuance.

Eisenhower introduced him to the Republican National Convention as “a man who has a special talent and ability to ferret out any kind of subversive influence wherever it may be found and the strength and persistence to get rid of it.”

“I should say this—that Pat doesn’t have a mink coat.” (From time to time, the camera had cut away to Pat, gazing at him adoringly off to one side in an armchair, tight-lipped.) “But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat. And I always tell her that she’d look good in anything.”

“One other thing I probably should tell you, because if I don’t, they’ll probably be saying this about me, too. We did get something—a gift—after the election. “A man down in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention the fact that our two youngsters would like to have a dog. And, believe it or not, the day before we left on this campaign trip we got a message from Union Station in Baltimore saying they had a package for us. We went down to get it. “You know what it was? “It was a little cocker spaniel dog in a crate that he sent all the way from Texas. Black-and-white-spotted. And our little

...more

Nixon could read the Constitution aloud to his two daughters. Pat, his devoted helpmeet, could sit within camera view, gazing lovingly upon him while knitting an American flag.

Liberal intellectuals were betraying themselves in a moment of crisis for liberal ideology. They saw themselves as tribunes of the people, Republicans as the people’s traducers. Liberals had written the New Deal social and labor legislation that let ordinary Americans win back a measure of economic security. Then liberals helped lead a war against fascism, a war conservatives opposed, and then worked to create, in the postwar reconversion, the consumer economy that built the middle class, a prosperity for ordinary laborers unprecedented in the history of the world. Liberalism had done that.

...more

Their liberal champions developed a distaste for them. One of the ways it manifested itself was in matters of style. The liberal capitalism that had created this mass middle class created, in its wake, a mass culture of consumption. And the liberals whose New Deal created this mass middle class were more and more turning their attention to critiquing the degraded mass culture of cheap sensation and plastic gadgets and politicians who seemed to cater to this lowest common denominator—public-relations-driven politicians who catered to only the basest and most sentimental emotions in men. Who

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

That a new American common man was emerging who, thanks to men like Nixon, thought he could be a Republican—to liberals this idea that the “comfortable” class associated with Ri...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

After Checkers, to the cosmopolitan liberals, hating Richard Nixon, congratulating yourself for seeing through Richard Nixon and the elaborate political poker bluffs with which he hooked the sentimental rubes, was becoming part and parcel of a political identity.

And to a new suburban mass middle class that was tempting itself into Republicanism, admiring Richard Nixon was becoming part and parcel of a political identity based on seeing through the pretensions of the cosmopolitan liberals who claimed to know so much better than you (and Richard Nixon) what was best for your country.

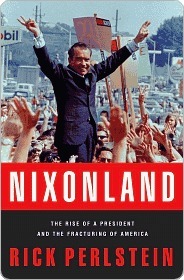

Call the America they shared—the America over whose direction they struggled for the next fifty years, whose meaning they continue to contest even as this book goes to press, even as you hold it in your hands—by this name: Nixonland. Study well the man at Nixonland’s center, the man from Yorba Linda. Study well those he opposed. The history that follows is their political war.

Who wanted to admit that America now had a blackguard a heartbeat away from the presidency?

Stature-enhancing trips to distant lands would always be a Nixon staple.

Joseph McCarthy had once been indulged by the Eisenhower administration as a useful, if distasteful, political asset. When he took on the army, he had to be cut loose for going too far. The task fell to the party’s other most prominent Red-baiter. Nixon had the credibility to shiv the cur without alienating the Republicans’ rank-and-file Red-baiters in the bargain.

McCarthy originally claimed dozens of subversives had infiltrated the Truman administration. Nixon claimed the new Republican administration had rousted “thousands.” (Eisenhower’s civil service commissioner later admitted they hadn’t found a single one.) Nixon also claimed that the new White House occupants had “found in the files a blueprint for socializing America.” Reporters asked him for a copy. Nixon claimed he had been speaking metaphorically.

He wrote his friend John Kenneth Galbraith, the (courtly) Harvard economist, “I want you to write the speeches against Nixon. You have no tendency to be fair.” Galbraith acknowledged that as a “noble compliment.”

Thus a more inclusive definition of Nixonland: it is the America where two separate and irreconcilable sets of apocalyptic fears coexist in the minds of two separate and irreconcilable groups of Americans. The first group, enemies of Richard Nixon, are the spiritual heirs of Stevenson and Galbraith. They take it as an axiom that if Richard Nixon and the values associated with him triumph, America itself might end. The second group are the people who wrote those telegrams begging Dwight D. Eisenhower to keep their hero on the 1952 Republican ticket. They believe, as did Nixon, that if the

...more

The president, running on a message of tail-finned peace and prosperity, commanded his pit bull just this once to “give ’em heaven.” Frank Nixon’s son found the advice awkward. Soothing bromides issuing from Nixonian lips tended to backfire; the image adjustment only reinforced the suspicion that Richard Nixon was only, well, image.

But Richard Nixon, you might say, did not win. For the first time since 1844, the party that won the White House captured neither house of Congress. Americans voted for the genial old general, the warm and wise national grandfather. They didn’t vote for his party. Nixon, everyone knew, was the partisan on the team. He was blamed for the congressional losses.

He modeled the program on the U.S. Homestead Act. He was rewarded in 1954 with a CIA-led military coup.

As the day of the debate approached, Nixon was swallowing drowsy-making antibiotics, but still losing sleep; fortifying himself against weight loss with several chocolate milk shakes a day, but still losing weight; losing color; adding choler. He looked pale, awful.

The press had recently become Nixon’s enemy of first resort.