More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

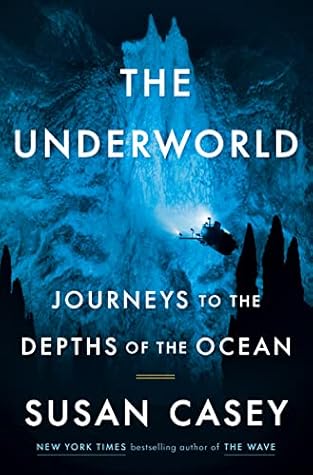

by

Susan Casey

Read between

January 22 - January 31, 2025

Even now, when every last crater on the moon has been named and interactive three-dimensional maps of Mars can be viewed on an iPhone, 80 percent of the seafloor has never been charted in any kind of sharp detail. Yet the deep ocean—defined as the waters below six hundred feet—covers 65 percent of the earth’s surface and occupies 95 percent of its living space.

How many undescribed species? What kind of wild rumpus goes on below while we’re preoccupied topside with our leveraged buyouts and political bickering and selfie apps?

In the deep, there are creatures that breathe iron and creatures with glass skeletons and creatures that communicate through their skin. Some of its creatures can turn themselves inside out. They might have two mouths or three hearts or eight legs. Or their bodies might consist of a thousand little bodies, a coordinated army. At least one deep-sea creature squirts yellow light. Some have see-through heads. Even the most ethereal among them can handle pressures that would crush a Mack truck.

There was also abundant garbage. Plastic was rampant, and so was every other kind of trash. Among the most common sights on the seafloor, he told me, were Budweiser beer cans: “It’s the preferred beverage of the environmentally unconscious.”

Japan, the world’s most tsunami-aware nation, has kept track of every treacherous wave since the sixth century CE, and those records show that the Cascadia tsunami raced across the Pacific basin, striking northeastern Japanese shores ten hours later—near midnight on January 27, 1700—razing houses, ruining crops, and battering the coastline until noon the next day. (The tsunami came as a shock because no one in Japan had felt the earthquake that spawned it: for nearly three centuries it was referred to as the “orphan tsunami.”

the most intriguing thing about hydrothermal vents is that they hold clues to the origin of life on this planet. How life emerged is a tetchy scientific debate that may never be resolved, but everyone agrees the recipe is exacting. First, you need water. Next, a steady supply of raw materials—chemical elements like hydrogen, sulfur, and carbon—and a site that’s just right for them to react. Then, somehow, there must be an ignition, a catalysis that helps this brew generate living cells. Finally: a stable mechanism that keeps the process going over time. This is not as straightforward as it

...more

“I define exploration as curiosity acted upon,” he said, stressing the power of that one little verb: to act. Nobody ends up orbiting the moon, or touring the hadal zone, or doing anything truly extraordinary by accident.

“If you’re not going to live with some degree of adventure, I think it’s a life half-lived.”