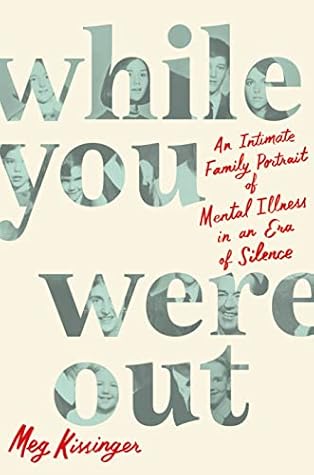

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

April 29 - April 30, 2025

The only good King is a dead King.

But nothing made sense to me any longer. Hurt people hurt people, as the saying goes.

But our family’s shorthand way of dealing with these situations—by simply not discussing them or making light of it—had an insidious way of fueling shame and blame where none was warranted.

people who live through trauma like the kind our family experienced tend to develop anxiety about being away. We become deeply vigilant.

I had a choice, Nat told me. I could feel sorry for myself and wallow in pity or choose to be happy and do what I could to make that happen.

But this is what suicide does. It deprives families of their primal need to grieve fully. The shame of how they died overshadows them. We don’t talk about people we love who end their own lives in the same way that we would if they had died of leukemia or had been killed in a skiing accident. It’s an especially lonely kind of grief.

Only love and understanding can conquer this disease.

It’s okay to be disappointed, but don’t get discouraged.

The more time I took to consider the trauma we had all been through, the easier I understood that two seemingly contradictory truths can exist simultaneously. My parents could be warm and loving but also reckless and flawed. Our family life could have been happy despite the tragedies.