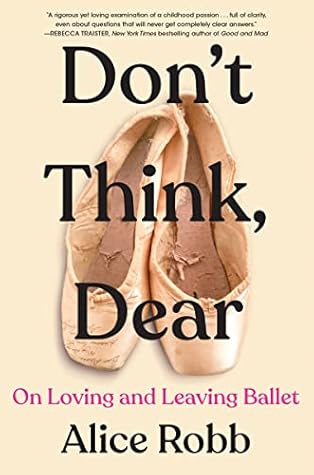

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Alice Robb

Read between

October 23 - November 3, 2024

How did we reconcile our past, and our residual love for ballet, with the feminist consciousness we eventually developed?

Ballerinas are as much a part of the lexicon of little-girlhood as Barbie:

The traits ballet takes to an extreme—the beauty, the thinness, the stoicism and silence and submission—are valued in girls and women everywhere. By excavating the psyche of a dancer, we can understand the contradictions and challenges of being a woman today.

proficiency at jacks was as much a social currency as packing the right lipstick in our plastic Caboodles.)

And as much as he believed that ballet was a calling, a serious endeavor, he considered the music even more important. “If you don’t want to see what’s on the stage,” he suggested in the 1965 interview with Life magazine, “close your eyes and for two dollars you get a beautiful concert.”

Balanchine scoffed at critics’ attempts to “understand” his ballets, insisting that they were meant only to be appreciated for their beauty. “When you have a garden full of pretty flowers, you don’t demand of them, ‘What do you mean? What is your significance?’” he said. “A flower doesn’t tell you a story. It’s in itself a beautiful thing.”

The “Balanchine technique” emphasized speed and energy, training dancers to perform the off-balance steps and jazzy distortions that became his trademark.

I was so accustomed to hearing renowned dancers described as the muses of great choreographers that I had come to think of it as an aspirational title. I hadn’t considered how outdated the term is, how sexist and objectifying—how it implies that a woman’s role is not to create art but to passively inspire it. Yet to be a muse for Balanchine was the highest honor, a label worn with pride.

The dancer’s life is inherently ritualistic: the repetition of the barre; the preparation of pointe shoes; the application of makeup. Her day is ordered and predictable, from class in the morning to rehearsal in the afternoon and a performance at night. So is the larger arc of her career, at least as she imagines it—from student to corps dancer to soloist.

Even a single dance session can have a significant impact: in a German study from 2007, psychologists invited a group of patients who had been hospitalized for depression to dance to the Jewish folk song Hava Nagila for half an hour. After just thirty minutes, they scored higher on measures of vitality and lower on symptoms of depression. (This effect can’t be attributed to the joyful music alone: patients who spent the same half-hour period listening to the song without dancing actually wound up feeling more depressed.)

The regimented discipline of ballet can be a lifeline for those suffering from trauma or going through uncertain times.

Our bodies were instruments and they belonged to other people: to choreographers and partners and directors—to men.

I have sometimes wondered, in my post-ballet life, if I have replicated that dynamic—if I internalized the doctrine of passivity, and if it affected my relationships.

She had imbibed the company ethos of what her biographer, Meredith Daneman, calls “vocational frugality, which preaches that one must be grateful to scrape a living for the privilege of doing what one loves.”

women, however celebrated, are still at the mercy of men; that her most important role was not as Princess Aurora or Giselle or the Swan Queen, but as her husband’s helpmeet.

It makes sense to me that dancers can’t always shed this obedient mindset when they exit the studio. That it can infect, even shape, their relationships with men in everyday life, and that even stars like Margot Fonteyn—invincible onstage—are susceptible to a childlike mentality, to acting the ingénue all the time.

We could have only one true allegiance, and it must be to ballet.

Female dancers occupy a unique position, as liberating in some ways as it is restrictive in others. They can devote themselves fully to their art and their ambitions without sacrificing their femininity.

The underage trainees in Paris were so frequently sold to upper-class men—often by their own desperate mothers—that the spread of syphilis was blamed on ballet.

Young, precarious, naïve about the world, and accustomed to following orders: ballerinas-in-training were the perfect victims.

Ballet attracts children who are already prone to perfectionism—who would rather repeat the same small movements over and over than play in the sandbox or run after a ball—then trains them to “self-correct”: to look in the mirror and scan for flaws.

“Purification and punishment seemed to go hand in hand.”

“Just try to look nice, dear,” he said, as he handed her “vitamins”—which she later came to believe were amphetamines. When she got back to New York, she was so weak that she could hardly walk. But, at less than ninety pounds, she was finally satisfied with her physique. “In my eyes, emaciation gave my upper body . . . swan-like definition,” she wrote.

Gelsey’s lifelong paranoia and self-loathing were like kindling, and cocaine the fuel that set the whole thing on fire.

What we do know is that she learned young, in the studio, that thinness and beauty meant attention and success; and that, as an adult, that lesson was reinforced by critics, fans, and lovers in the real world.

I wondered if I could trace my unnatural standards back to ballet; I wondered if I was trying—now that it was too late—to look like the dancer I’d never become, as if trying to prove my fidelity to an ex-lover who had moved on.

Excessive “mirror gazing” and “mirror checking” are both occupational necessities for dancers and clinical features of body dysmorphic disorder.

The culture of ballet is so powerful, the ideals so seductive, that even not-so-serious students are at risk for body dysmorphia: one study, published in the journal Psychopathology, showed an elevated rate of eating disorders among girls who took as few as two or three classes a week and had no intention of pursuing a career in ballet.

I would go to the bathroom and be surprised, and then relieved, to see a dark cloth instead of my own imperfect face. I felt that I’d been somehow absolved of responsibility for my appearance.

But in Balanchine’s absence, his “ideal” had hardened into law. By the time I arrived at SAB, the standard was so specific and severe that even actresses and gymnasts seemed to have it easy by comparison.

When the writer Alana Massey shrank to a size zero in her early twenties, she was at first delighted by the flood of male attention that rushed in. But she soon realized that, as much as men appreciated her new body, they were turned off by her refusal to deviate from the routine that kept it small.

But dancers are exempt from this double bind. They don’t have to hide the colossal effort they make. For them, dietary sacrifices don’t signal vanity or an adherence to old-fashioned ideals, but commitment to high art.

In the morning, I look at my face as if it’s a first draft:

Pain seemed so inevitable that I had taught myself to ignore it. It was more important to spare his feelings and preserve the mood than to feel better.

thirty percent of women say they experienced pain the last time they had sex, compared with just five percent of men. And for some, the pain is excruciating: as many as one in six women suffer at some point from vaginismus, a condition in which their vaginas contract in painful spasms when touched.

emergency room visits for pubic grooming injuries increased by a factor of five; the most at-risk group was young women.)

perhaps ailment was a feature central to that experience.” Dainty and fragile, she felt like an ideal woman—“like a crystal ballerina.”

Women are incentivized to downplay and conceal their discomfort; if we admit we are in pain, we risk being cast as hypochondriacs or hysterics.

According to Leigh Cowart’s Hurts So Good: The Science and Pleasure of Pain on Purpose, the force of balancing en pointe on one foot is equivalent to letting the full weight of a grand piano fall on a single toe.

Pain is the body’s warning system: nature’s request that we stop what we are doing. But from an early age, dancers are inducted into a perverse relationship with pain. It isn’t a sign that the body is under stress; it’s a source of pride, a sign of progress—something to be ignored, if not outright relished.

Ballet dancers are acutely in tune with their bodies, right down to the nerve receptors in their skin—but they are experts at pushing through.

It is easy to see a dancer’s acceptance of pain as resignation—as a concession to a toxic culture. And it may be a symptom or a side effect of living and working in a system that endorses self-destruction. But the ability to endure—to tolerate enormous pain and keep going—can also be called resilience.

Ballet is an ephemeral art. “Because it has no text, ballet dies every day, to be reborn as the next ballet,” the critic Joan Acocella wrote in the New York Review of Books in 1994.

the ballet mother, a subset of stage mom, is pushy, striving, ambitious; overinvolved in her daughter’s life and overinvested in her career. Perhaps she herself once aspired to dance; perhaps she regrets the career she never had. (The mothers of Center Stage and Black Swan were thwarted by flat feet and pregnancy, respectively.) She knows where to shop for custom leotards and where to find the best private coaches. She organizes her life around her daughter’s training. She might drive her daughter hours to and from class. She might leave her husband, and even her other children—she might say

...more

In language that wouldn’t be out of place on horse-breeding forums, they fret over their children’s changing bodies.

Raising a dancer involves such a commitment that even a well-balanced parent may become excessively invested in her daughter’s career and feel personally let down if she changes her mind. (A 2015 analysis by FiveThirtyEight estimated the cost of a ballet dancer’s training—including fifteen years of class tuition, summer programs, pointe shoes, leotards, and tights—at over a hundred thousand dollars.)

My feelings toward ballet, in the following years, veered between longing and regret and feminist disdain. I would take open classes for a week, then swear them off forever. I would avoid the subject with a new friend, then decide that it was the most important thing for her to know about me.

Proffitt and other psychologists in the growing field of embodied cognition are discovering, contra-Descartes, how our perceptions of the world—how steep a hill looks; how fast a tennis ball is coming toward us—are not just a function of our brain, but of our bodies and our physical abilities.

Sally Rooney, who has been called the voice of my generation, confided in an interview that, growing up, she fantasized about being “a brain in a jar.” Her characters—especially her young women—have a remarkably high tolerance for sitting. They read in the library or lie in bed all day, forgetting to eat or tend to their bodies. Rooney is often praised for writing such relatable characters.

Structural change can feel impossible; it’s easier, for many women, to just go numb, to distance themselves from their bodies—to pretend they don’t have a body at all.