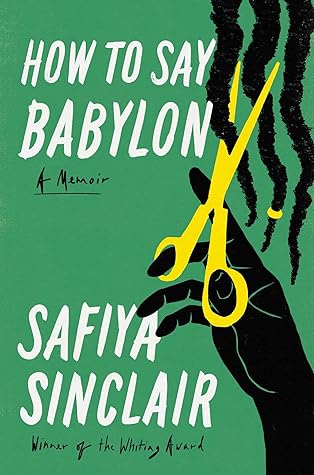

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Babylon was the government that had outlawed them, the police that had pummeled and killed them. Babylon was the church that had damned them to hellfire. It was the state’s boot at the throat, the politician’s pistol in the gut. The Crown’s whip at the back. Babylon was the sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people, and the corruption of Black minds. It was the threat of destruction that crept, even now, toward every Rasta family.

This splintering would eventually become the painful undoing of my family a generation later, because it encouraged most Rastafari to individualize their livity at home, with impunity. There, in the privacy of their own households, each Rasta bredren could be a living godhead, the king of his own secluded temple.

There is an unspoken understanding of loss here in Jamaica, where everything comes with a rude bargain—that being citizens of a “developing nation,” we are born already expecting to live a secondhand life, and to enjoy it. But there is hope, too, in our scarcity, tolerable because it keeps us constantly reaching for something better.

The perfect daughter was whittled from Jah’s mighty oak, cultivating her holy silence. She spoke only when spoken to. The perfect daughter was humble and had no care for vanity. She had no needs, yet nursed the needs of others, breastfeeding an army of Jah’s mighty warriors. The perfect daughter sat under the apple shade and waited to be called, her mind empty and emptying. She followed no god but her father, until he was replaced with her husband. The perfect daughter was nothing but a vessel for the man’s seed, unblemished clay waiting for Jah’s fingerprint.

“Poetry is the best of what I have come to love about this world,” my mother said.

When he was happy, we were invincible. I was almost twelve and didn’t yet think of happiness as a disappearing myth. I craved these velvet hours, wishing we could stay this way, despite Babylon.

Here in the gathering numbness was our matrilineal mark: Each of us turned to stone overnight. Thrown, ripple after ripple, into the same strange sea. Delivered by some grief the night before. Here, the women of my family all met under one sign, stamped by what confining fates we had been handed.

I was the first—forever standing at the end of the road or at the beginning of one.

She might as well have given me the blade. Maybe she could see me after all. Maybe she had always known. That I was not the weapon. I was only the wound.

Later I confessed to him that I felt myself being pulled irrevocably toward some tragic fate. That I was doomed for a love so violently passionate that it would draw blood. That I longed to be taken apart entirely. How else would anyone know I was alive? The Old Poet sighed. “Life is not like a novel, kid,” he said.

She was passing down something about the world to me just then—the world as she found it and survived it, ever since her mother died. She’d been trying to escape for a long time. Not just the man who had grabbed her on the bicycle as a child, or the street louses she had to fight off on her way home from school, but eventually the advances of her own grandfather from whose drunken fondling she ran away. This she would only tell me about years later. The world that sent her running and hiding from unwanted hands and mouths and tongues was the same one I now moved through—and she expected

...more

I wanted so much to be like my mother, so patient and forgiving, to be a person other people clung to. To laugh with my whole mouth open and not have a care, as she had that morning.

She was right. I was foolish, more foolish than any of them. And even worse, I was weak. Marred by my double axe—both sentimental and a hopeless masochist, I kept expecting something different from my father every time. Having loved him first, I somehow believed he could become something worthy of loving again. I believed it still, even then. I believe it still, even now.

All day I am prodded, all night I am probed. My skirt is lifted, my flower dissected. My silver ransacked without permission. Each day I am learning to live in a town built on the bones of the enslaved. I gasp awake in a country birthed from one terrible wound and then another, and I am unable to ignore America’s own red lineage. Here, no tree is ever just a tree. Here, every rolling field has been nursed on stolen sweat, every green acre sprung from blood.

In my father’s house, I would always slip back into that girl again. She was everywhere in here, and out there, in the cane. The smiling Rasta girl who had no idea what doom was coming, even though she reminded me what to do in the face of it. Guiding me to persevere, no matter the weather, to harden around my own dreams like a pearl. My father couldn’t set that Rasta girl free in his mind. He clasped onto that daughter like driftwood, keeping him afloat in Babylon’s torment, saving him from drowning in his life’s crashing disappointment. He would never see me as I was. He would never hear me.

...more

My father’s eyes glistened now as he watched me singing, so I sang louder. I didn’t know when I would come home again, or what future would ever be possible for us. But trilling under the crackle of the resort’s night air, I wanted him to know I had been listening all this time. I might have left Rastafari behind, but I always carried with me the indelible fire of its rebellion. And when I returned to America, I would walk taller. Babylon would never frighten a daughter like me.

Father unbending, father unbroken. Father I was forged in the fire of your self. Father your first daughter now severed at the ankles, Father your black machete. Father a flag I am waving/father a flag I am burning. Fathering my exorcism. Father the harsh brine of my sea. Making sounds only the heart can feel. Father a burrowing insect, his small incision. Daughter entering this world a host. Father the soft drum in my ear. Father Let me in.