More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? —PSALMS 137

Echoes of runaways still hung in the air of the deepest caves, where Maroon warriors had ambushed English soldiers who could not navigate the terrain. The English would shout commands to each other, only to hear their own voices bellowing back at them through the maze of hollows, distorted as through a dark warble of glass, until they were driven away in madness, unable to face themselves. Now more than two centuries later, I felt the chattering night wearing me mad, a cold shiver running down my bones. A girl, unable to face herself.

Where I would watch the men in my family grow mighty while the women shrunk. Where tonight, after years of diminishment under his shadow, I refused to shrink anymore.

She cooked and cleaned and demurred to her man, bringing girlchild after girlchild into this world who cooked and cleaned and demurred to her man. To be the humbled wife of a Rastaman. Ordinary and unselfed. Her voice and vices not her own. This was the future my father was building for me.

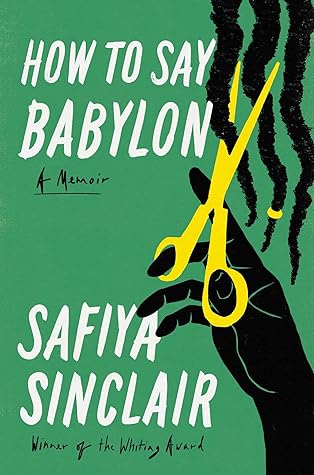

I understood then that I needed to cut that woman’s throat. Needed to chop her down, right out of me.

To carve my own way forward, I had to first make my way back. To where the island’s loom and my family’s yarn made one knotted thread. I had to follow until I could find just where this story’s weaving began: decades before I was born, before my father was born. Before he had a song for this strange captivity, and a name for those he longed to burn. And before I learned too well how to say it. Babylon.

The Rastas pushed dangerously against those barricades of Babylon, tentatively eyeing the officers armed with bayonets as they flashed the heavy rain free from their dreadlocks. Their hopes buzzing near-electric, they watched the sky for the first glimpse of the Ethiopian airliner that carried the man they believed to be a living god, the emperor Haile Selassie.

On this damp April morning in 1966,

No visitor to Jamaica had ever received such a welcome; no dignitary or celebrity, not even Queen Elizabeth II, who had visited only a month before, was greeted with such jubilation.

were emblazoned in holy garb, flanked head to toe in the roaring red, gold, and green of the Ethiopian flag, the adopted symbol of Rastafari, worn by Rasta bredren in dashikis, rain-soaked tams, and military insignia, and Rasta sistren in ankle-length whites, bright scarves, and tasseled headwraps.

Rastafari movement’s creation in 1933, when a visionary street preacher named Leonard Percival Howell heeded Marcus Garvey’s call to “Look to Africa for the crowning of a Black King,” who would be the herald of Black liberation.

Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia, the only African nation never to be colonized,

Black man, born Ras Tafar...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

And though the Rastafari movement was nonviolent, they were the nation’s black sheep, feared and despised by a Christian society still under British rule, forced to live on the fringes as pariahs.

They were the unemployed and unemployable, the constant victims of state violence and brutality, the ones the government jailed and forcibly shaved, the ones brutally beaten by the police.

Rasta communes were burned island-wide in a weekend of terror, where more than 150 Rastas were dragged from their homes, imprisoned, and tortured, and an unknown number of Rastas were killed.

From those psalms of Jewish exile came the Rastafari’s name for the systemically racist state and imperial forces that had hounded, hunted, and downpressed them: Babylon.

Babylon was the government that had outlawed them, the police that had pummeled and killed them. Babylon was the church that had damned them to hellfire. It was the state’s boot at the throat, the politician’s pistol in the gut. The Crown’s whip at the back. Babylon was the sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people, and the corruption of Black minds. It was the threat of destruction that crept, even now, toward every Rasta family.

Zion, the Rastafari’s name for both the promise of liberation and the soil of Africa, to where they believed it was their destiny to repatriate.

a young singer named Rita Marley,

she saw the mark of a black stigmata in the center of his palm. “This is the Man!” she screamed. “This is Him!” By the time her husband, Bob, returned a few months later from Delaware, where he had been visiting family, she had grown her dreadlocks and set them both on a path of staunch devotion to Rastafari, believing they should spread His Imperial Majesty’s message through music.

When the emperor, who was an Orthodox Christian, finally sat down with Rastafari leaders, he told them very plainly he was not God. But his message, instead of deterring them, was widely seen by Rastas as irrefutable proof that he was in fact a living god, because only God would be capable of showing such humility. Only God Himself would deny His divinity.

What did it mean, after all, to be the living answer to the fraught question of Black survival?

Before my father came to believe he was God, a man named Haile Selassie walked here, among the same blue ferns he did, following that one blue note between rock-steady and the clink of the country river.

And though he was only a toddler when the emperor visited, Haile Selassie’s influence would take staunch roots in him, irrevocably changing the course of his life, and my family’s life with it.

Long after his own people rejected him in a coup, he was still here, at the airport next to the tiny fishing village of White House where my family first made a life.

Here there was no slick advert of a “No Problem” paradise, no welcome daiquiris, no smiling Black butler. This was my Jamaica. Here time moved slowly, cautiously, and a weatherworn fisherman, grandfather or uncle, may or may not lift a straw hat from his eyes to greet you.

Children were not allowed to use the latrine, since we were in danger of falling in, so we were each tasked to keep a plastic chimmy in the house instead, emptying it into the sea every morning.

I gorged on almonds and fresh coconut, drinking sweet coconut water through a hole my mother gored with her machete, scraping and eating the wet jelly afterward until I was full. Each day my joy was a new dress my mother had stitched for me by hand.

My father was not from the seaside, so he never felt at home at White House. He was a man who lived among fishermen but did not eat fish, adhering in all ways to an ascetic Rasta existence: no drinking, no smoking, no meat or dairy, all tenets of a highly restrictive way of living the Rastafari called Ital.

Next to the airport, looming along the borders of our village, were hotels with high walls made of pink marble and coral stone, flanked on top by broke-glass bottles, their sharp edges catching the light in cruel warning: To live in paradise is to be reminded how little you can afford it.

This was the fantasy tourists wanted to inhabit, sunbathing at hotels along the coast named “Royal Plantation” or “Grand Palladium,” then getting married on the grounds

where the enslaved had been tortured and killed. This was paradise—where neither our history nor our land belonged to us. Every year Black Jamaicans owned less and less of the coast that bejeweled our island to the outside world, all our beauty bought up by rich hoteliers, or sold off to foreigners by the descendants of white enslavers who earned their fortunes on our backs, and who still own enough of Jamaica today to continue to turn a profit.

Now most of Montego Bay’s coastline is owned by Spanish and British hoteliers—our new colonization—and most Jamaicans must pay an entrance fee to enter and enjoy a beach. Not us.

Today, no stretch of beach in Montego Bay belongs to its Black citizens except for White House. My great-grandfather had left the land title and deed so coiled in coral bone, so swamped under sea kelp and brine, that no hotelier could reach it. This little hidden village by the sea, this beachside, was still ours, only.

Hello and I love you said a reedy voice from the sea, speaking the kind language of a small child, and so I stepped in, first one foot in the sinking sand and then another, warm sea froth snaking around my tiny ankles, then rising quickly to my knees.

She never told my father about my near-drowning, I discovered nearly three decades later. They had both wished for a Rasta family for so long that she could not bear to name the danger we’d only narrowly escaped—danger that my father soon began to foresee

So began our first secret, mother and daughter, our own little creation lore, cloistered as a clamshell around us. This was the first time my mother had saved me from my own calamitous devices, but it would not be the last.

He understood then what Rastas had been saying all along—systemic injustice across the world flowed from one massive, interconnected, and malevolent source, the rotting heart of all iniquity: what the Rastafari call Babylon.

“Rasta is a calling. A way of life.” There is no united doctrine, no holy book to learn the principles of Rastafari, there was only the wisdom passed down from the mouths of elder Rasta bredren, the teachings of reggae songs from conscious Rasta musicians, and the radical Pan-Africanism of revolutionaries like Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X.

Garvey had told his followers to look to Africa for a Black Redeemer, and it was in Ethiopia that Howell found proof of him: the Conquering Lion of Judah, the Emperor Haile Selassie I.

Sections of the movement eventually broke off into three main groups: the Mansion of Nyabinghi, the Bobo Shanti, and the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

This splintering would eventually become the painful undoing of my family a generation later, because it encouraged most Rastafari to individualize their livity at home, with impunity. There, in the privacy of their own households, each Rasta bredren could be a living godhead, the king of his own secluded temple.

He believed that if he kept playing his reggae with righteous conviction, this crooked world would wake up and change. If he kept playing, he could save Black people’s minds, and we would reach Zion, the promised land in Africa.

What the tourists couldn’t discern, as they drank and ate dinner while my father sang and flashed his dreadlocks onstage, was his true motivation for singing. Night after night he sang to burn down Babylon, which was them.

there was only one answer to whatever he said. Yes, Daddy. Whatever lecture or conjecture, Yes, Daddy. A keen face of listening, then Yes, to whatever he said. Accepting his bitters like spring water.

“I saw you kissing up another woman in the back seat of the taxi while my sister sitting there in the front seat listening to the two of you, silent like stooge.” Her voice quavered at the memory. She could not reconcile this voiceless disciple my mother had become.

Rasta bredren believed women were more susceptible to moral corruption because they menstruated.

His bandmates were only temporary stand-ins for this sense of belonging, and for a sweet few months, as we played in our family band that summer under one harmony, he saw himself, himself, himself.

In violent retribution, Alexander Bustamante, the white prime minister at the time, targeted Rastafari island-wide, ordering the military to “Bring in all Rastas, dead or alive.” Years later, I would learn the rest of this brutal history on my own, horrified as the details unfurled before me. For one long weekend in April 1963, beginning on the day that Rastas call “Bad Friday,” the Jamaican army went on a rampage, raiding and destroying several Rasta encampments all over western Jamaica.