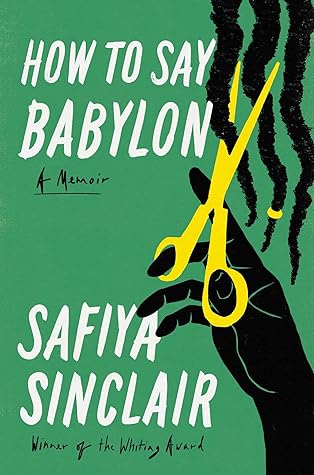

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

The more of this world I had discovered, the more I rejected the cage my father had built for me.

Babylon was the government that had outlawed them, the police that had pummeled and killed them. Babylon was the church that had damned them to hellfire. It was the state’s boot at the throat, the politician’s pistol in the gut. The Crown’s whip at the back. Babylon was the sinister and violent forces born of western ideology, colonialism, and Christianity that led to the centuries-long enslavement and oppression of Black people, and the corruption of Black minds. It was the threat of destruction that crept, even now, toward every Rasta family.

To live in paradise is to be reminded how little you can afford it.

Under the tenets of Rastafari, a woman’s divine purpose was to bear children,

Rasta bredren believed women were more susceptible to moral corruption because they menstruated. I was destined to be unclean.

There was more than one way to be lost, more than one way to be saved.

A book, I soon learned, was time travel. Each page held irrefutable power.

It was then I learned that there are three main sects of Rastafari. The Mansion of Nyabinghi is the oldest, and the one from which all the other sects were born. Nyabinghi is militantly Pan-Africanist, believing in Haile Selassie as the reincarnation of God on earth, in Black unification, liberation, and repatriation to Ethiopia. The Twelve Tribes of Israel is the most liberal Rastafari sect, welcoming wayward uptown Jamaican youth and white foreigners as members; they eat meat and believe in Jesus Christ. The Bobo Shanti, the newest sect of the three, live closed off from society as a

...more

For the men of Rastafari, the perfect daughter was everything a woman was supposed to be. The perfect daughter was whittled from Jah’s mighty oak, cultivating her holy silence. She spoke only when spoken to. The perfect daughter was humble and had no care for vanity. She had no needs, yet nursed the needs of others, breastfeeding an army of Jah’s mighty warriors. The perfect daughter sat under the apple shade and waited to be called, her mind empty and emptying. She followed no god but her father, until he was replaced with her husband. The perfect daughter was nothing but a vessel for the

...more

Perhaps it was true what my father said. That I lacked discipline, the way any nine-year-old lacks discipline—I didn’t always listen, I was skeptical. I doubted his gospel. I was curious. I touched the flame simply because it was burning. Because discipline always seemed to me the pin that held the butterfly in the display case. Work maketh the man. Day after day, I swung over those words, and saw ahead of me a life withering slowly under all his multiplying decrees. Day after day my heart bucked up against it. I was never going to be the perfect daughter. A grin of mischief opened ever so

...more

How poetry could cast a light on a meager world and make it boundless. How pain could be transformed into something beautiful.

A thought, I understood then, and its incendiary mind, could outlive itself. A well-made word could outspan carbon, and bone, and halved uranium.

I knew then that as long as I had a word that leapt aflame in my mind, I would always be living in an age of wonder.

I knew, as every Jamaican child knows, that no sentence directed to your parents should begin with the word “So.”

The word “gyal” was an insult in Rasta vernacular and was never used for a girl or woman who was loved and respected. Calling someone a “gyal” was a marker of her unworthiness, used with the intent to hurt and belittle. When he called me “gyal” in the froth of his anger, the insult was my fledgling womanhood. My looming impurity. For weeks I felt that word like a knife between my legs. Gyal. A dirty word. Pinning me to that moment.

I glided into the bookstore on a sunbeam, buzzing as I picked out my textbooks, pressing my face inside to smell their pages, glossy new worlds waiting for me. This was what I imagined Christmas must be like, cradling my new books.

He seemed to care immensely about what people thought of him, and as I grew older, the more his contradictions became plain. He despised Babylon, while yearning for its trappings. And when he did not defend me against Mrs. Pinnock, it struck me how much grace he offered these meat-eating strangers, and how little for us.

Here, the women of my family all met under one sign, stamped by what confining fates we had been handed. A girl had no choice in the family that made her.

Plain as the purple glare on his face, the truth, hasty and pitiful, now revealed its innermost parts to me—a Rastaman was not ascetic or untouchable or particularly saintly. He was just another creature boiling under the tropic heat, collapsing under his carnal and banal desires, like every other man.

She had lived on a cowrie shell dream for so long she didn’t know how to plan more than a week into the future.

“I’d promise to lend you one,” he said, his eyes twinkling from behind his glasses, “but I don’t know how you take care of books yet.” His Trinidadian accent rising and falling like a wave, he continued, “When I lend out a book, I assume an inevitable loss. That the book in many ways belongs to the reader now.”

“But you write notes in your books, don’t you?” he asked. “No…” Apart from my high-school textbooks, I always shared books with my siblings, and never had a book that was just for me, one that I could make a permanent mark in to share my thoughts with my future self. “Well, you should always write in the margins as you read,” he said. “Make that a regular practice.” “Yes, sir,” I said.