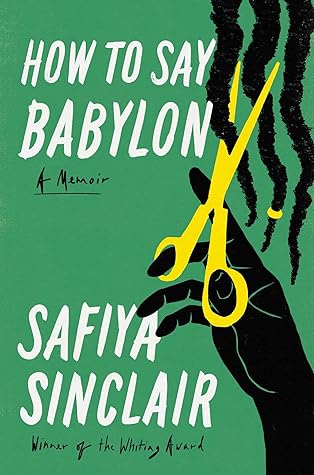

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

this is where he was born.

Where I would watch the men in my family grow mighty while the women shrunk. Where tonight, after years of diminishment under his shadow, I refused to shrink anymore.

BEFORE THE MUSIC CAME THE rain.

From those psalms of Jewish exile came the Rastafari’s name for the systemically racist state and imperial forces that had hounded, hunted, and downpressed them: Babylon.

Long after his own people rejected him in a coup, he was still here, at the airport next to the tiny fishing village of White House where my family first made a life. His flame burned alive in my father, who was god of our whole dominion, who slept with one watchful

eye on my purity and one hand on his black machete, ready to chop down Babylon, if it ever crept close.

Today, no stretch of beach in Montego Bay belongs to its Black citizens except for White House. My great-grandfather had left the land title and deed so coiled in coral bone, so swamped under sea kelp and brine, that no hotelier could reach it. This little hidden village by the sea, this beachside, was still ours, only.

Hello and I love you said a reedy voice from the sea, speaking the kind language of a small child, and so I stepped in,

Our history was the sea, my mother told me, so I could never be lost here. And, if I listened closely enough to the water, it would always call me home.

Babylon’s “ism and schism”—colonialism, racism, capitalism, the temptations of greed in white American and European culture, the mental chains of Christianity, and all the evil systems of western ideology that sought to destroy the Black man.

What the tourists couldn’t discern, as they drank and ate dinner while my father sang and flashed his dreadlocks onstage, was his true motivation for singing. Night after night he sang to burn down Babylon, which was them.

I curled into my father’s lap in the passenger seat and studied his face, the way his eyes only looked ahead. His paranoia that I would be invaded by Babylon would dominate my childhood for years to come, but none of us, not even my mother, knew how far he was willing to go to prevent it.

At last, we lived away from the heathens. In our own yard, with a gate that he could use to keep Babylon out. Here, where he was godhead and architect of our new world, he would create the purest Rasta family.

While my father molded our view of the wicked world and its hidden history, my mother shaped our love of learning and our sense of wonder.

While he warned us of Babylon, she showed us Zion.

My hair had grown matted, flecks of lint and old matter knotted down the length of each dreadlock, a nest containing every place I had laid my head. It hadn’t been brushed in two years.

I thought about what she had said. How poetry could cast a light on a meager world and make it boundless. How pain could be transformed into something beautiful. Monique’s words may have crafted my hurt, but words could also unmake it.

knew then that as long as I had a word that leapt aflame in my mind, I would always be living in an age of wonder.

Shame, too, grew slowly with me now, as I noticed for the first time not only a river swelling between me and my father, but that he was the one who fed its tributaries.

I was afraid I would be nothing else but a wound in this world. A thorn in the side of a man who said he was my father. Most days I lunged headfirst into danger if I could find it, searching for my own death knell, rummaging for a sign to absent myself from all worlds.

Maybe she could see me after all. Maybe she had always known. That I was not the weapon. I was only the wound.

stood at the top of the slope and looked out at my inheritance, our rented house, old and filled with mice. There, my father and his cruel tongue slept. Outside, the darkness spread for miles, pregnant with what was unseen in the Jamaican countryside. The trees surrounding me loomed tall and quiet, and I thought of the one big knife in the kitchen, the one my mother used to chop her almonds, its rickety handle, the steel stained almond-red.

There was no world for me except the one I had been building in my mind. No way ahead. I knew I could not live here with my father and survive.

All I needed was a room and a pen and some light to read at night.

Where my father pressured clay onto an empty frame to build the perfect daughter in his own image, the Old Poet chiseled away at me, determined to perfect the poet within.

All winter I let the wave carry me back to the river, remembering the folk songs of my kin. At night I follow the trail of women who came before me, slip into a tangled past where their hum seals my ears. I wander through their underworld and eat of its bounty. Soon poem after poem fills my mouth with pomegranate seeds. At night I burn a fever, unspooling red from my throat, determined to make sense of my doomed matriarchy. My inheritance. My mother lore. Bending over the page in my basement apartment, I try to write the ache into something tangible.

Instead of turning in a final paper for his poetry class, I write him a letter describing in vivid detail my father’s hands at my throat, being throttled breathless in the night, the black machete. I drift until I startle awake in my bed, gasping.

Bringing myself to a boil by the portable heater, I begin to work, trying in vain to weave the mother lore. I try to write down my memories but still, he kills me in the night.

The summer humidity holds me to choking while I pull poems out of my ear like weeds.

I am heavy with tropical rain, and all that has been brimming dark and unseemly inside me. All this fury.

Feeling weightless now, the heat of the gone talons burned my shoulders as I read, and I knew. There was no more red thread. No more red. I had pulled it loose and given it my best words. Here on the page, blank as a beach, my mind’s waves rippling. Home was poetry and what it had forged of me.