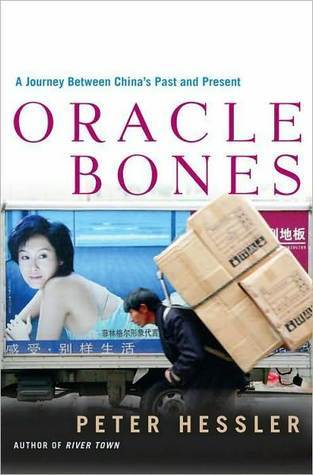

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 31 - August 7, 2010

This book was researched from 1999 to 2004, a period whose events are still resonating. I expect that in the future we will learn more about these occurrences, and my depiction is not intended to be comprehensive or definitive. My goal has been to follow certain individuals across this period, recording how their lives were shaped by a changing world.

POLAT WAS THE first person who made me think about the sheer size and range of China. When you compared the Uighurs and the Han Chinese, they seemed a world apart in every respect: geography, culture, language, history. They were like antipodes contained within the borders of a single country.

His point is simple: censorship captures the imagination, but the process of creation might be even more destructive. In order to write a story, and create meaning out of events, you deny other possible interpretations. The history of China, like the history of any great culture, was written at the expense of other stories that have remained silent.

One evening, I meet Galambos for a drink in Beijing, and the conversation turns to history. He explains that people have a natural tendency to choose certain figures and events, exaggerate their importance, and then incorporate them into narratives.

I find this to be a fascinating view about how history is created. It is about stories that become enlarged and ultimately become assumed truth.

Aloke liked this

“That’s how history is formed in their minds,” he says. “It’s through these important people and events. But while studying Chinese history, you learn that maybe some of these events didn’t happen, or they were very minor, or a lot of other things happened that were in fact very important. The Chinese say that every five or six hundred years a sage appeared. In reality I would say it’s more fluid, more complex; there’s a lot more stuff going on. Obviously, that’s no way to teach history. You can’t just say, ‘There’s a lot more stuff going on.’ It’s inevitable that you have to pick out certain

...more

I asked how many students he taught. “There are ninety-four,” he said. “How many classes?” “One class.” “You have ninety-four students in one class?” “Yes,” he said. “It’s very crowded!” After the conversation, I tried to imagine what it would be like to teach English to ninety-four middle-school kids in a remote Yangtze village.

I have a Facebook friend who teaches in a middle school in Kenya who has this many students in his class. It seems incomprehensible that you could teach a class that large!

The sheer complexity of the modern landscape had a lot to do with it. If you visited a bridge that had been bombed out by Americans, restored by Chinese, and then rented out to small-scale entrepreneurs who sold Titanic ice cream bars, it wasn’t surprising that people reacted to the outside world in illogical ways.

The Dutch men seemed uncomfortable until Mr. Wang changed the subject. He talked about modified starch and how it is different from normal, unmodified starch. The distinction was subtle and I had difficulty grasping it; at last Wim spoke up. He wanted to clarify things. “Basically, modified starch is the same material as crude oil,” he said. “It’s a carbohydrate.”

Pages and pages of this book we’re devoted to Chinese corn starch. More than I ever wanted to know about corn starch! This kind of diversion made the book less interesting. A lot of Information about how China and the Chinese operated but way too much about corn starch!

I looked at Emily and realized that the question wasn’t important to her. Since coming to Shenzhen, she had found a job, left it, and found another. She had fallen in love and she had broken curfew. She had sent a death threat to a factory owner, and she had stood up to her boss. She was twenty-four years old. She was doing fine. She smiled and said, “I don’t know.”

“Every once in a while I think, I’m getting these people asylum, but I’m basically helping to destroy Uighur culture,” he said. “Their kids adjust so fast. For the grandkids, it will just be an oddity that they were Uighur. But this happens with all groups in America. I’m sure the descendants of the German revolutionaries who came over in the 1840s weren’t quite as keen on revolution. It’s the same thing with any small, hunted group.”

“You’ve broken the law,” he said. “You are required to carry your passport, and you must request permission before you report. You are not allowed to sleep on a cultural relic. All of these things are against the law. You could be fined, but we will waive it today. You must never do this again. Do you understand?”

I am not enjoying this book so much as the first one I read. Just now he talks for a while about Oracle bones. Then he talks for a while about the effort to get the Olympics in Beijing in 2008. Then he finally talks about something interesting which is going camping in an abandoned Town near the great wall outside of Beijing. He stumbles into a nearby town that is having an election and is detained by the police for four hours. He is questioned for much of that for hours then released. That is actually a pretty interesting story with a little bit of humor tossed in!

“It’s such a giant step,” Takashima says. “This step to writing, after thousands of years of oral communication. You know, the history of writing isn’t that long. But once it began, civilization progressed by leaps and bounds. It’s tremendous. Writing is really the great engine for progress in human civilization.

He told me that many Chinese needed psychological help. “People should spend more time looking inside themselves,” he said. “A person and history are the same—by that, I mean that a personal history is enormous. An individual can be even more complicated than a society. But there isn’t any time for the Chinese to examine themselves like that.

There is some effort to say that the author travels around China talking with the common people. In this case the common person is a Chinese movie star! He spends a lot of time on the creation of that film and the people involved.

But a writer’s work moved in the opposite direction. I started with living people and then created stories that were published in a distant country. Often, the human subjects of my articles couldn’t even understand the language in which they were written. From my perspective, the publishing world was so remote that it seemed half real.

The book covers the stories the author was writing for US magazines. The time frame included 9/11 and a visit of President Bush to China. Pages about the consideration of changing Chinese characters to another format for communication. Sort of a technical view of language and writing. Not really an interest grabber for me.