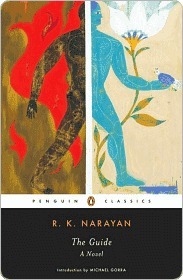

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Formerly he would have said, “Who will eat this? Give me coffee and idli, please, first thing in the day. These are good enough for munching later.”

Raju himself was not certain why he had advised that, and so he added, “If you do it you will know why.” The essence of sainthood seemed to lie in one’s ability to utter mystifying statements.

This sort of inquiry soon led me to think that I had not given sufficient thought to the subject. I never said, “I don’t know.” Not in my nature, I suppose. If I had the inclination to say “I don’t know what you are talking about,” my life would have taken a different turn.

My mother came out of the kitchen formally, smiled a welcome, and said, “Be seated on that mat. What’s your name?” she asked kindly, and was rather taken aback to hear the name “Rosie.” She expected a more orthodox name. She looked anguished for a moment, wondering how she was going to accommodate a “Rosie” in her home.

I was considered a model prisoner. Now I realized that people generally thought of me as being unsound and worthless, not because I deserved the label, but because they had been seeing me in the wrong place all along. To appreciate me, they should really have come to the Central Jail and watched me.

“Forget the walls, and you will be happy,” I told some of the newcomers, who became moody and sullen the first few days.

For the first time in his life he was making an earnest effort; for the first time he was learning the thrill of full application, outside money and love; for the first time he was doing a thing in which he was not personally interested.

“Will you tell us something about your early life?” “What do you want me to say?” “Er—for instance, have you always been a yogi?” “Yes; more or less.”