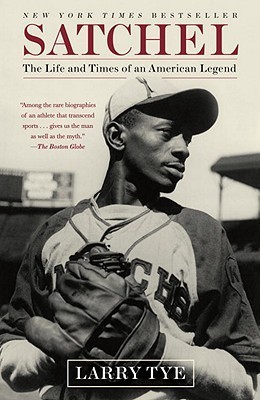

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Second-guessers, the Browns’ boss pointed out, made one fatal mistake in evaluating Satchel: “They thought he was human.”

The Browns also dusted off the old riddle about Satchel’s age. In 1952 they listed his date of birth as “Sept. 11, 1892, 1896, 1900 (or) 1904—take your pick.” The following year they streamlined the entry in their press guide to “date unknown—‘aged.’”

Who else but Satchel could toss a bar of soap onto a slippery wall-mounted dish and make it stay? Once might be luck, but he did it twice in a row.

Veeck had an experiment of his own for his pitching star. Photographers snapped shots of twenty-five hitters standing in the batter’s box with just their hips showing. “We painted out all possible marks of identifications—socks, and so on—and showed the photographs to our pitching staff,” he said. Satchel picked out eighteen from their batting stance alone. The next best guesser got six right. He might not know a young Ted Williams or Joe DiMaggio by face, but Satchel remembered how they stood at the plate and what pitches they typically hit and missed. It paid dividends. He generally stopped

...more

Hornsby had predicted from the start that bringing blacks into baseball would be a disaster, and he did his best to ensure it was. Satchel, as the only black on the Browns, bore the brunt of that bigotry. When Hornsby fined the pitcher for missing an exhibition game in Corpus Christi, Texas, it was not another case of Satchel living by his own clock. It was Jim Crow flexing his muscle, with the bus driver who transported players from the train station to the hotel barring Satchel from boarding.

What Satchel went through in the Majors was different from the indignities he had endured before. Many umpires saddled him with a strike zone that was shorter and narrower than for his Caucasian counterparts.

White pitchers hit black batters too many times for it to be chance (Pillette says his manager paid him fifty dollars for clipping Jackie Robinson when Jackie was with Montreal).

‘Those sons of bitches can beat you but they can’t eat you.’

antediluvian,

In 1961 he returned to the Monarchs, then signed with the minor league Beavers in Portland, Oregon.

Some baseball historians insist he was not even the best in blackball. Smokey Joe Williams threw at least as hard and almost as long. Bullet Joe Rogan fielded, hit, and blended a fastball and curve with exquisite control. John Donaldson had a curveball faster than most pitchers’ fastballs. The Foster half brothers, Rube and Willie, could also make claims to the throne, along with Richard “Cannonball Dick” Redding, Hilton Smith, and José Méndez. In the end, however, Satchel was the frame of reference, the one everyone compared themselves to and whom historians perpetually lift up to the

...more

The mighty Hank Aaron goes one better, saying that if Satch had been a Major Leaguer from the start “he might have won 300 games with his outfielders sitting down.” Historian Bill James ranks Satchel seventeenth on his list of the hundred greatest baseball players of all time, six spots ahead of Cy Young. “Satchel deserves to rank, with Cy Young, Lefty Grove, and Walter Johnson, as the guys that you talk about when you’re trying to figure out who was the greatest [pitcher] that ever lived,” argues James. Journalists Mark McGuire and Michael Sean Gormley place Satchel at thirty-three in their

...more

“How good was Satchel Paige since we don’t know, at least statistically, how good he was? Better than most, and on many days, all.”

“Methuselah was my first bat boy,” Satchel joked.

Names were another Satchel specialty. Call a fastball a fastball and no one paid attention. Fireball, bullet, and rocket were so hackneyed, even in mid-century, that they seemed flat. Whipsy-dipsy-do was another matter. Satchel loved to riff on his pitches: “I got bloopers, loopers and droopers. I got a jump ball, a be ball, a screw ball, a wobbly ball, a whipsy-dipsy-do, a hurry-up ball, a nothin’ ball and a bat dodger. My be ball is a be ball ’cause it ‘be’ right were I want it, high and inside. It wiggles like a worm. Some I throw with my knuckles, some with two fingers. My whipsy-dipsy-do

...more

The more reaction his names drew, the more creative he got, giving birth to the Four-day Rider, Slow Gin Fizz, Butterfly, Step-n-Pitch-It, Eephus, Thoughtful Stuff, Two-hump Blooper, Midnight Creeper, Submariner, Sidearmer, Alley Oops, Drop Ball, Single Curve, Double Curve, and Triple Curve.

Twenty years later the Hall relented, sort of. It would let in one black a year based on his record in the old Negro Leagues, starting of course with Satchel, but it would be to a wing separate from other honorees. “This notion of Jim Crow in Baseball’s Heaven is appalling,” Jim Murray wrote in 1971 in the Los Angeles Times. “What is this—1840? Either let him in the front of the Hall—or move the damn thing to Mississippi.”

Then he answered his question in a way that unsettled the baseball elite, which had hoped that Satchel’s entry into the Hall would divert attention from a history of exclusion to its belated gesture of inclusion. “I don’t think the white is ready to listen to the colored yet. That’s why they’re afraid to get a black manager—they’re afraid everybody won’t take orders from him.”

His dream was to be the first black manager, or at least a serious pitching coach. He wanted players to value him for what he knew rather than owners for his fan appeal. He never got that chance.

“the Paige tragedy is that, by his excellence, he proved that 50 years worth of black-league players had been wronged more severely than white America ever suspected.