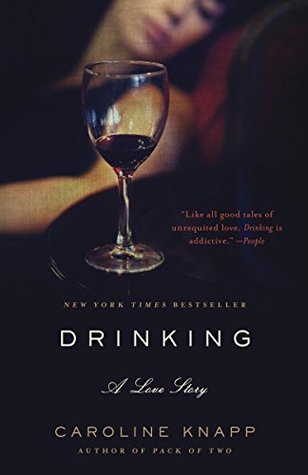

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I drank when I was happy and I drank when I was anxious and I drank when I was bored and I drank when I was depressed, which was often.

The knowledge that some people can have enough while you never can is the single most compelling piece of evidence for a drinker to suggest that alcoholism is, in fact, a disease, that it has powerful physiological roots, that the alcoholic’s body simply responds differently to liquor than a nonalcoholic’s.

Drinking alone is what you do when you can’t stand the feeling of living in your own skin. Boswell describes this in his Life of Johnson: “I drink alone,” Johnson explains, “to get rid of myself, to send myself away. Wine makes a man better pleased with himself.”

a true alcoholic is someone who’s turned from a cucumber into a pickle; you can try to stop a cucumber from turning into a pickle, but there’s no way you can turn a pickle back into a cucumber.

attaching all your hopes and fantasies to something—or someone—outside yourself almost always has disastrous results.

“Insight,” he said, “is almost always a rearrangement of fact.”

Sobriety is less about “getting better” in a clear, linear sense than it is about subjecting yourself to change, to the inevitable ups and downs, fears and feelings, victories and failures, that accompany growth. You do get better—or at least you can— but that happens almost by default, by the simple fact of being present in your own life, of being aware and able, finally, to act on the connections you make.

Not long ago I heard a woman in her ninth month of sobriety say that before she quit drinking, she had only two emotions, anxiety and despair. “Now I have, like, too many to count,” she said, “and some of them suck, but some of them are really, really good.” Almost everyone in the room knew what she meant.