More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

She understood that drinking was more dangerous and she understood why: smoking could ruin my body; drinking could ruin my mind and my future. It could eat its way through my life in exactly the same way a physical cancer eats its way through bones and blood and tissue, destroying everything.

There are moments as an active alcoholic where you do know, where in a flash of clarity you grasp that alcohol is the central problem,

Shouldn’t I prove to myself that I could go a day—just one simple day—without a drink?

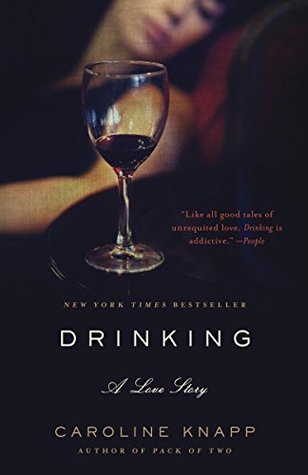

Alcohol had become too important. By the end it was the single most important relationship in my life. A love story. Yes: this is a love story.

and there is no simple reason why this happens, no single moment, no physiological event that pushes a heavy drinker across a concrete line into alcoholism. It’s a slow, gradual, insidious, elusive becoming.

looking around at everyone else, at their clear eyes and well-rested expressions.

I was drinking every night, drinking to get drunk, to obliterate.

Tennessee Williams said that he never wrote without first drinking wine. William Styron used liquor, and often, not to help him write but to help him think, a means, he writes, of letting his mind “conceive visions that the unaltered, sober brain has no access to.”

I once heard alcoholism described in an AA meeting, with eminent simplicity, as “fear of life,” and that seemed to sum up the condition quite nicely. I,

That’s classic logic among functioning alcoholics: Over time the drink itself becomes the reward, the great compensation for our ability to keep it all together during the day, and to keep it all together so well.

Toward the end of my drinking it would occur to me that my professional life managed to move forward precisely because it was the one area in my life where I never got drunk. Even with an occasional hangover I was able to grow, able to see my mistakes and learn from them, able to gauge my own limits and to hone my understanding of where further work needed to be done. My vision didn’t get muddied in the office in quite the same way it did in my personal life,

The truth gnaws at you. In periodic flashes like that I’d be painfully aware that I was living badly, just plain living wrong. But I refused to completely acknowledge or act on that awareness, so the feeling just festered inside like a tumor, gradually eating away at my sense of dignity.

You know and you don’t know. You know and you won’t know, and as long as the outsides of your life remain intact—your job and your professional persona—it’s very hard to accept that the insides, the pieces of you that have to do with integrity and self-esteem, are slowly rotting away.

This is a fairly common experience for drinkers: you look up one day and realize you’re the only one left in the bar.

The drinking felt more like an experiment, an act based on some vague hypothesis I’d begun to form about the connection between liquor and anxiety, liquor and sadness, how one corrected the other.

he had a kind of intensity that made you feel he could see right through you.

Sitting in front of him felt like sitting before God.

Like drinking stars. That’s how Mary Karr describes it in her memoir, The Liar’s Club, a line she picked up from her mother. She drank red wine and 7-Up one night from a bone-china cup when she was a kid and she felt that slow warmth, almost like a light. “Something like a big sunflower was opening at the very center of my being,” she writes, and when I read that, I knew exactly what she meant. The wine just eased through me in that Greek restaurant, all the way through to my bones, illuminating some calm and gentler piece of my soul.

Drinking with my father always made me feel like that. It wasn’t so much that he got any less God-like when we drank; it was that I’d feel more God-worthy, less intimidated with a few drinks in me, more self-assured. I could plop down next to him on the sofa and talk.

Enough? That’s a foreign word to an alcoholic, absolutely unknown. There is never enough, no such thing.

You’re always after that insurance, always mindful of it, always so relieved to drink that first drink and feel the warming buzz in the back of your head, always so intent on maintaining the feeling, reinforcing the buzz, adding to it, not losing it. A woman I know named Liz calls alcoholism “the disease of more,” a reference to the greediness so many of us tend to feel around liquor, the grabbiness, the sense of impending deprivation and the certainty that we’ll never have enough. More is always better to an alcoholic; more is necessary. Why have two drinks if you can have three? Three if you

...more

Why and how? Toward the end of my drinking I’d go to a party and promise Michael I wouldn’t drink too much. He’d plead: “Just take it easy, okay? Watch yourself,” and I’d swear: “I won’t. I don’t want to get too drunk.” I’d mean that, of course, and I’d start out by measuring myself: one glass of wine the first half hour, one glass the second, and so on. But then something would snap, some uncontrollable process would kick in, and all of a sudden it would be two or three hours later and I’d be on my sixth or tenth or God knows what glass of wine, and I’d be plastered. I couldn’t ac...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The knowledge that some people can have enough while you never can is the single most compelling piece of evidence for a drinker to suggest that alcoholism is, in fact, a disease, that it has powerful physiological roots, that the alcoholic’s ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

The need is more than merely physical: it’s psychic and visceral and multilayered. There’s a dark fear to the feeling of wanting that wine, that vodka, that bourbon: a hungry, abiding fear of being without, being exposed, without your armor. In meetings you often hear people say that, by definition, an addict is someone who seeks physical solutions to emotional or spiritual problems.

Most alcoholics I know experience that hunger long before they pick up the first drink, that yearning for something, something outside the self that will provide relief and solace and well-being. You hear echoes of it all the time in AA meetings, that sense that there’s a well of emptiness inside and that the trick in sobriety is to find new ways to fill it, spiritual ways instead of physical ones. People talk about their fixations with things— a new house they’re looking to buy, or a job they’re desperate for, or a relationship—as though these things have genuinely transformative powers,

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

some spiritual carrot on a stick promising comfort and relief—and it’s important for me to remember that: for years it was party shoes and riding boots; later it would be alcohol. Same intent, same motivation; different substance.

As soon as I could sit up in my mother’s lap, I started rocking, rocking myself back and forth, and I did this for years.

I can see the rocking now as a first addiction of sorts. It calmed me, took me out of myself, gave me a sense of relief.

Discomfort+Drink=No Discomfort.

For a long time, when it’s working, the drink feels like a path to a kind of self-enlightenment, something that turns us into the person we wish to be, or the person we think we really are. In some ways the dynamic is this simple: alcohol makes everything better until it makes everything worse. And when drinking makes things better, it does so with such easy perfection, lifting you, shifting you—just like that—into another self.

process, a Pavlovian phenomenon of persistent reinforcement: this feels good, the way this glass of white wine flows from bottle to glass to throat to brain, the way it tingles and warms and lightens. This feels good, the way a group of us gather around a table, elbow to elbow, united in the camaraderie of drink and laughter and reward. Later, the sensations would grow more specific: this feels good, this snifter of Cognac warming in the palm, and this flute of Champagne, cool and delicate to the touch as mother of pearl, and this tumbler of gin, clear and icy and laced with lime: it feels

...more

I loved those moments, that sense that the world had boiled down to such simple elements:

me and Sam and the two glasses on the table; everything else—the clink of waiters clearing tables, the low buzz of talk from others around us—just background music. Drinking was the best way I knew, the fastest and simplest, to let my feelings out and to connect, just sit there and connect, with another human being. The comfort was enormous: I was an easier, stronger version of myself, as though I’d been coated from the inside out with a warm liquid armor.

That may be one of liquor’s most profound and universal appeals to the alcoholic: the way it generates a sense of connection to others, the way it numbs social anxiety and dilutes feelings of isolation, gives you a sense of access to the world. You’re trapped in your own skin and thoughts; you drink; you are released, just like that.

In many ways alcoholism has the feel of a psychological safety net, something a drinker constructs over a period of many years by making connections between feelings, like an emotional game of connect-the-dots.

Fear+Drink=Bravery;

Drinking, in a general sense, gave me a way to rewrite such pieces of history, a way to address whatever lingering confusion I had about the person I’d been brought up to be.

Again, simple math: I grew up in a confusing home and the drink made the confusion go away; it provided the easiest way out, an escape from my internal life.

Of course, the problem with self-transformation is that after a while, you don’t know which version of yourself to believe in, which one is true. I was the hardened, cynical version of me when I was with James and Elaine, and I was the connected, intimate version of me when I was with Sam, and I was the genteel, sophisticated version of me when I was with my relatives, and honestly, after a while I didn’t know which was which, where one began or ended,

One of the first things you hear in AA—one of the first things that makes core, gut-level sense—is that in some deep and important personal respects you stop growing when you start drinking alcoholically. The drink stunts you, prevents you from walking through the kinds of fearful life experiences that bring you from point A to point B on the maturity scale. When you drink in order to transform yourself, when you drink and become someone you’re not, when you do this over and over and over, your relationship to the world becomes muddied and unclear. You lose your bearings, the ground underneath

...more

And then, tragically, the protection stops working. The mathematics of transformation change. This is inevitable. You drink long and hard enough and your life gets messy. Your relationships (with nondrinkers, with yourself) become strained. Your work suffers. You run into financial trouble, or legal trouble, or trouble with the police. Rack up enough pain and the old math—Discomfort+Drink=No Discomfort—ceases to suffice; feeling “comfortable” isn’t good enough anymore. You’re after something deeper than a respite from shyness, or a break from private fears and anger. So after a while you alter

...more

One morning you wake up and open your eyes. Your head feels like it weighs way too much, so much it hurts to move: you feel a throbbing behind one of your eyes, or in your temple. A sharp pain, a steady ache. Your brain hurts, as though the fluid between your brain and skull is thick and inflamed. You feel mildly nauseated and you can’t tell if you need to eat or if eating would make you sick. Inside, everything feels jittery and loose, like a car with bad wiring.

I remember getting drunk. I remember how the drink mixed with the rhythm of the music and gave me a sense of connection to my own body, gave it permission to move,

Looking back I can see how certain patterns were beginning to develop, certain classically alcoholic ways of managing feelings and conflicts in relationships that would grow more entrenched and complicated over time.

Almost by definition alcoholics are lousy at relationships. We melt into them in that muddied, liquid way, rather than marching into them with any real sense of strength or self-awareness.

We become so accustomed to transforming ourselves into new and improved versions of ourselves that we lose the core version, the version we were born with, the version that might ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Feel conflicted? Drink. Insecure? Have a drink. Angry? Drink.

Alcoholics compartmentalize: this was classic behavior, although I wouldn’t have known that back then. I’ve heard the story in AA meetings time after time: alcoholics who end up leading double lives—and sometimes triple and quadruple lives—because they never learned how to lead a single one, a single honest one that’s based on a clear sense of who they are and what they really need.

desperately—it’s another classic impulse among alcoholics, to seek validation from the outside in—and