More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 30, 2018 - March 8, 2019

My officers were ready to discard a great idea because it came from a lowly enlisted man. Fortunately, I happened to overhear his recommendation. Every leader needs big ears and zero tolerance for stereotypes.

I took only the risks that I thought my boss would want me to take, risks I could defend within my job description and authority.

The usual practice, I was told, was to wait to be directed in what to do. I don’t need parrots in my organization. Marshall kept asking me for permission to change rudder by a degree or add half a knot to our speed. If all you give are orders, then all you will get are order-takers. Since my goal was to create self-starters, I finally said, “Hey, K.C., it’s your ship, take responsibility for it. Don’t ask permission; do it.”

We would constantly plan for “what if” situations:

never took attendance.

the idea of community service spread:

not because they had to, but because they wanted to.

it would do wonders for the employees to get away from the routine of work,

My officers knew that they could always use me in their leadership toolkits. They never hesitated to knock on my door and say, “Hey, Captain, next time you’re out walking around the ship, Sonarman Smith really aced that databank,”

The more I went around meeting sailors, the more they talked to me openly and intelligently. The more I thanked them for hard work, the harder they worked.

the third- and second-class petty officers were so honored to be chosen that they worked hard enough for several of their teams to outshine those supervised by senior people.

simply by challenging them:

the program was designed to infect the jaded vets with their enthusiasm.

If I got my unit operating independently and delivering outstanding results, they could concentrate on other issues and do their jobs better—that’s what any boss wants, as well as bragging rights.

we made it our business to learn what his needs would be.

A lot of it is organizational attitude and mind-set.

Furthermore, they were expected to take on a project or two that would improve the ship’s quality of life, or a military process that affected the entire organization. My theory is that when people see their contemporaries undertaking big projects, they will understand that doing so gets you a top evaluation.

When it is time to inform the bottom performers that, in fact, that’s what they are, I have found that asking them how they would rate their own performances is effective.

My first move was to cancel our diversity training program. I could have been fired for that, but in my view it was common sense that any program that produced such awful results was clearly ineffective. I had no intention of allowing anything ineffective on Benfold. In its place I substituted unity training,

Unity training was one of the few programs I chose not to delegate; I conducted it myself.

I’m a big believer in getting resentments and grumbling out in the open, where they can do a lot less damage.

Articulating the feelings that your people are afraid to speak is a large part of what leaders, including ship captains, do for a living.

having fun with your friends creates infinitely more social glue for any organization than stock options and bonuses will ever provide.

When I took command I had three top priorities: to get better food, implement better training, and make as many promotions as I could every year.

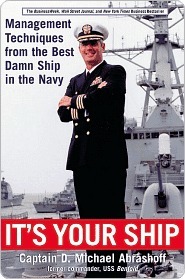

Lead by example; listen aggressively; communicate purpose and meaning; create a climate of trust; look for results, not salutes; take calculated risks; go beyond standard procedure; build up your people; generate unity; and improve your people’s quality of life.

People ask how I got along with the other commanding officers. I have to be honest: less well than I should have. If one ship in a ten-ship group is doing conspicuously well, it’s hard to imagine the other nine feeling good about it. Yet I never stopped to consider those feelings, which, of course, included my own competitiveness. That was a mistake on my part. I certainly made life uncomfortable for the nine other commanding officers in my battle group. Their sailors would complain that Benfold was doing this or that, so why couldn’t they?

In hindsight, I could have been much more supportive of my colleagues—for example, by telling them in advance what we were doing, so they could join us voluntarily

excellence upsets some people. It always has and always will. Live with it.

the most effective managers work hard at showing people how to find their own solutions, and then get out of their way.

Optimism rules. And the corollary: Opportunities never cease.

hold commanding officers personally responsible for the retention and disciplinary rates of their crews.