More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I always used to be a little sad when the children went out, but now I wish they’d go so I’d be left alone to write.

I was about to sit down right away to write, but there was still the kitchen to straighten:

It’s two in the morning. I got up to write: I can’t sleep. Yet again it’s the fault of this notebook. Before, I’d immediately forget what happened at home; now, instead, since I began to write down daily events, I hold on to them in my memory and try to understand why they occurred. If it’s true that the hidden presence of this notebook gives a new flavor to my life, I have to acknowledge that it isn’t making it any happier.

We’re always inclined to forget what we’ve said or done in the past, partly in order not to have the tremendous obligation to remain faithful to it.

Old people give great importance to the sun.

I need to be alone sometimes. I would never dare confess it to Michele, I’d be afraid of upsetting him, but I dream of having a room all for myself.

Maybe my mother was too with me when I was a child. “Sew,” she’d always say. “Study.” When I was older, as soon as I stopped studying she assigned me domestic chores. She never allowed me to remain idle, she never forgot about me. If for a moment she didn’t see me, she came into my room and asked what I was doing. “A woman should never be idle,” she said.

I said I was going to see my mother, write some letters. He said that he hasn’t written personal letters for years, and that a man who works a lot ends up with no true friends but only business acquaintances, necessary friendships, calculated, almost. “We remain alone,” he said.

Now, when the house is empty and silent, I think of my mother, who spends hours sitting and embroidering, absorbed in memories of the past.

Often, faced with men’s bad moods, I wonder what they would do if instead of only their office job they had, like every woman, so many different problems to confront and solve.

“Mirella is a child. I’m sure you’ve thought about it and come to tell me that you’ve decided to leave, not to disturb her further. Isn’t that so?” I asked in a decisive tone that allowed only a confirmation. “No,” he answered calmly and with equal decisiveness. “On the contrary. I came to tell you that I’ll never leave her.”

often have a desire to confide in a living person, not only in this notebook. But I’ve never been able to. Stronger than the desire to confide is the fear of destroying something that I’ve been constructing day by day, for twenty years, the only thing I possess.

I’ve gone several days without writing. I’ve noticed that after writing a lot I feel more depressed, weaker.

He’s very jealous of Marina: when he’s at home, studying, he always calls to see where she is, to know if it’s true that she went to see a friend. And yet he always finds her; she must be a good girl, docile, not very intelligent.

Sometimes I think that I haven’t loved Michele for many years now, that I continue to repeat that phrase out of habit, not noticing that loving feelings no longer exist between us, and have been replaced by others, perhaps equally valid, but completely different. I think again of the anxiety with which I waited for Michele as a fiancé, of the desire we had to be alone, to talk, of the time that went by rapidly, on the thread of looks and words, and of the tedium that now descends when we’re alone together, and no outside distraction, not the radio or the movies, comes to save us.

I was really convinced that it was still love, and until Mirella confessed she was afraid that her life would resemble mine, I was also convinced that I was happy. Maybe, in reality, I still am, but what I feel when I’m with Michele is a cold happiness, very different from what I feel when Guido talks to me or takes my hand. These candid gestures are love and the gestures I perform with Michele, instead, are only affection or solidarity or habit, even those rare, more intimate ones: pity, or, rather, compassion for human weakness.

I know that my reactions to the facts I write down in detail lead me to know myself more intimately every day.

The others are sleeping, at this hour: sleep cancels the day they’ve been through, and the new day appears, free of the weight of the preceding days, which I, on the other hand, preserve in these pages as if in an exorbitant account book in which no debt is ever forgiven.

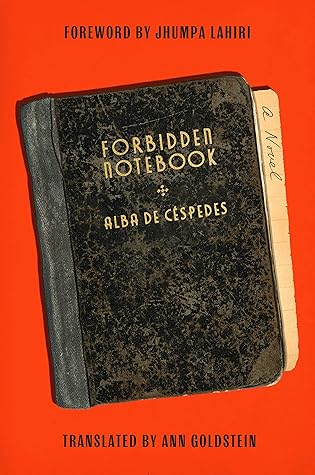

It was Sunday and the tobacconist didn’t want to sell me the notebook, I remember. He said, “It’s forbidden.” Then I was seized by an irrepressible desire to possess it, I hoped that in it I would be able to fulfill without guilt my secret desire to still be Valeria.

In this notebook the volume of my life entirely spent for others is present to me almost materially, with the weight of the pages, with the marks of my dense writing.

She’s certain to find it someday and find in it a motive to dominate me as I dominate her for what she did with Riccardo.