More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

My love of the films did not grow from any forgiveness of his crime. That forgiveness never happened, even though I understood the circumstances and the context: sex between grown men and teenage girls was normalized at the time, the subject matter of songs and films; Gailey has said she forgives him; Polanski himself was a victim, his mother murdered at Auschwitz, his father held in concentration camps, his wife and unborn child murdered by the Manson Family. There’s no denying the horror of Polanski’s backstory—after all, two of the terrors of the twentieth century happened to him,

...more

The poet William Empson said life involves maintaining oneself between contradictions that can’t be solved by analysis. I found myself in the midst of one of those contradictions.

I’d spent my life being disappointed by beloved male artists: John Lennon beat his wife; T. S. Eliot was an anti-Semite; Lou Reed has been accused of abuse, racism, and anti-Semitism (these offenses are so unimaginative, aside from everything else). I didn’t want to compile a catalogue of monsters—after all, wasn’t the history of art simply already that?

If I were writing an honest autobiography of the audience—I mean the audience of the work of monstrous men—that autobiography would need to balance these two elements: the greatness of the work and the terribleness of the crime. I wished someone would invent an online calculator—the user would enter the name of an artist, whereupon the calculator would assess the heinousness of the crime versus the greatness of the art and spit out a verdict: you could or could not consume the work of this artist. A calculator is laughable, unthinkable. Yet our moral sense must be made to come into balance

...more

We don’t always love who or what we’re supposed to love. Woody Allen himself famously quoted Emily Dickinson: “The heart wants what it wants.” Auden said it more nicely, as he said almost everything more nicely: “The desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews.” The desires of the audience’s heart are as crooked as corkscrews. We continue to love what we ought to hate. We can’t seem to turn the love off.

I began to see that these questions had been haunting me for years—as a film critic, a book critic, simply a viewer and consumer and fan of art. For a long time, this question seemed my private purview—a lonely puzzle of pleasure and responsibility, almost a kind of hobby, like needle felting or co-rec soccer. The question seemed personal, and the answers contingent—upon my mood, upon the individual artist and the specific work. In those years, the years leading up to 2016, I didn’t know we were about to enter a new landscape where heroes would fall, one after another, and the response to

...more

How do we separate the maker from the made? Do we undergo a willful forgetting when we decide to listen to, say, Wagner’s Ring cycle? (Forgetting is easier for some than others; Wagner’s work has rarely been performed in Israel since 1938.) Or do we believe genius gets special dispensation, a behavioral hall pass?

And how does our answer change from situation to situation? Are we consistent in the ways we apply the punishment, or rigor, of the withdrawal of our audience-ship? Certain pieces of art seem to have been rendered unconsumable by their maker’s transgressions—how can one watch The Cosby Show after the rape allegations against Bill Cosby? I mean, obviously it’s technically doable, but are we even watching the show? Or are we taking in the spectacle of our own lost innocence? And is it simply a matter of pragmatism? Do we withhold our support if the person is alive and therefore might benefit

...more

These questions became more urgent as the years went by—as, in fact, we entered a new era. Here’s the thing about new eras: You don’t really recognize them as they show up. They’re not carrying signposts. And maybe “new era” is not quite the right phrase. Maybe we entered an era where certain stark realities began to be clearer to people who had heretofore been able to ignore them.

hold up for a minute: who is this “we” that’s always turning up in critical writing? We is an escape hatch. We is cheap. We is a way of simultaneously sloughing off personal responsibility and taking on the mantle of easy authority. It’s the voice of the middlebrow male critic, the one who truly believes he knows how everyone else should think. We is corrupt. We is make-believe. The real question is this: can I love the art but hate the artist? Can you? When I say “we,” I mean I. I mean you.

Sleeping with your partner’s child—that requires a special kind of creep. I can hear you arguing this, you Woody-defenders, even now, in my brain, saying that Woody was not Soon-Yi’s parent, that he was her mother’s boyfriend, that I’m being hysterical. But I have a special knowledge of this kind of relationship: I was raised by my mother and her boyfriend Larry. And I assure you that Larry was my parent.

In fact, to accept the idea that Woody was not Soon-Yi’s parent does violence to the very idea of my relationship with Larry, one of the most cherished of my life. And perhaps that was the key to my response, when the news of Woody and Soon-Yi came out: I was even more disgusted by the whole mess than I might’ve been otherwise, because I myself had a mother’s boyfriend in my life—in my case, someone I adore and respect to this day. The story of Woody and Soon-Yi—at least the way it came to me—perverted this delicate relationship. In other words: My response wasn’t logical. It was emotional. —

Style looks easy, but is not. This is true about Annie Hall across the board. All the things that look easy are not: the pastiche form; the integration of schlocky jokes with an emotional tenor of ambivalence; the refusal of a happy ending, tempered by the spritzing about of a general feeling of very grown-up friendliness.

To watch Annie Hall is to feel, for just a moment, that one belongs to the human race. Watching, you feel almost mugged by the sense of belonging. That fabricated connection can be more beautiful than love itself. A simulacrum that becomes more real than the thing it represents. And that’s how I define great art. Look, I don’t get to go around feeling connected to humanity all the time. It’s a rare pleasure. And I was supposed to give it up just because Woody Allen behaved like a terrible person? It hardly seemed fair.

My own ability to experience pleasure, specifically pleasure arising from consuming art, was imperiled all the time—by depression, by jadedness, by distraction. And now I was finding I must also take into account biography; an artist’s biography as a disrupter of my own pleasure.

we tell ourselves we’re having ethical thoughts when really what we’re having are moral feelings. We arrange words around these feelings and call them opinions: “What Woody Allen did was very wrong.” But feelings come from someplace more elemental than thought. The fact was this: I felt upset by the story of Woody and Soon-Yi. I wasn’t thinking, I was feeling. I was affronted, personally somehow.

Which of us was seeing more clearly: The one who had the ability—some might say the privilege—to remain untroubled by the filmmaker’s attitudes toward females and his history with girls? Who had the ability to watch the art without committing the biographical fallacy? Or the one who couldn’t help but notice—maybe couldn’t help but feel—the antipathies and urges that seemed to animate the project?

Manhattan is a work of genius. But who gets to say? Authority says the work shall remain untouched by the life. Authority says biography is fallacy. Authority believes the work exists in an ideal state (ahistorical, alpine, snowy, pure). Authority ignores the natural feeling that arises from biographical knowledge of a subject. Authority gets snippy about stuff like that. Authority claims it is able to appreciate the work free of biography, of history. Authority sides with the male maker, against the audience.

All these things can be true at once. Simply being told that Allen’s history shouldn’t matter doesn’t achieve the objective of making it not matter.

When you’re having a moral feeling, self-congratulation is never far behind. You are setting your emotion in a bed of ethical language, and you are admiring yourself doing it. We are governed by emotion, emotion around which we arrange language. The transmission of our virtue feels extremely important, and strangely exciting. Reminder: not “you,” not “we,” but “I.” Stop sidestepping ownership. I am the audience. And I can sense there’s something entirely unacceptable lurking inside me.

everyday deed and thought, I’m a decent-enough human. But I’m something else as well, something more objectionable. The Victorians understood this feeling; it’s why they gave us the stark bifurcations of Dorian Gray, of Jekyll and Hyde. I suppose this is the human condition, this sneaking suspicion of our own badness. It lies at the heart of our fascination with people who do awful things. Something in us—in me—chimes to that awfulness, recognizes it in myself, is horrified by that recognition, and then thrills to the drama of loudly denouncing the monster in question. The psychic theater of

...more

This impulse—to blame the other guy—is in fact a political impulse. I talked earlier about the word “we.” “We” can be an escape hatch from responsibility. It can be a megaphone. But it can also be a casting out. Us against them. The morally correct people against the immoral ones. The process of making someone else wrong so that we may be more right.

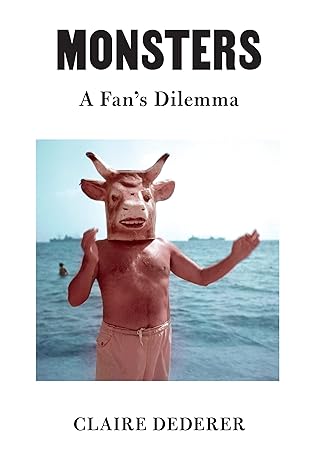

I called these men monsters, and so did the rest of the world. But what did the word actually mean? There were things I liked about the word: It is balls-out, male, testicular, old world. It’s a hairy word, and has teeth. It’s a word that means: something that upsets you. The dictionary has it as something terrifying, something huge, something successful (a box-office monster).

The feminism I knew of was a feminism that found fault. That pointed—j’accuse. As I understood it, there were two ways of being: you could be a feminist who called men monsters, or you could ignore the problem. I considered myself a feminist, but at the same time I had an uneasy feeling that the pointing was not the whole story. A feminism that denounced, that punished, was starting to feel like a trap. My feminism, which was in essence a liberal ideology, was coming into conflict with my increasingly leftist politics, my growing desire to look at a bigger picture of where and how material

...more

I had asked, at first, what we should do with the art made by monstrous people. But, as I thought about it more, I realized I wasn’t looking for a prescription, exactly. I have published two memoirs, which means I am, I suppose, a memoirist, though it’s a very uncomfortable label. As a memoirist, I struggled for years to separate prescription from description. Good memoir describes the writer’s life; it doesn’t tell the reader what to do with her own life. I was noticing that same impulse at work here: I was less interested in a clear-cut solution than in anatomizing the problem. What happens

...more

The word “monster” doesn’t hold up well in the face of such dispassionate curiosity, such drive to understand. It starts to seem a little silly or overblown or, let’s go all the way with it, hysterical.

And of course no one is entirely a monster. People are complex. To call someone a monster is to reduce them to just one aspect of the self.

It meant: someone whose behavior disrupts our ability to apprehend the work on its own terms.

A monster, in my mind, was an artist who could not be separated from some dark aspect of his or her biography. (Maybe it works for light aspects too. Maybe there are golden monsters. But it seems very unlikely, or at best very rare.)

That’s how the stain works. The biography colors the song, which colors the sunny moment of the diner. We don’t decide that coloration is going to happen. We don’t get to make decisions about the stain. It’s already too late. It touches everything. Our understanding of the work has taken on a new color, whether we like it or not. The tainting of the work is less a question of philosophical decision-making than it is a question of pragmatism, or plain reality. That’s why the stain makes such a powerful metaphor: its suddenness, its permanence, and above all its inexorable realness. The stain is

...more

When someone says we ought to separate the art from the artist, they’re saying: Remove the stain. Let the work be unstained. But that’s not how stains work.

The stain begins with an act, a moment in time, but then it travels from that moment, like a tea bag steeping in water, coloring the entire life. It works its way forward and backward in time. The principle of retroactivity means that if you’ve done something sufficiently asshole-like, it follows that you were an asshole all along.

can’t even bypass our knowledge of what he’s done. We can’t bypass the stain. It colors the life and the work. Does the stain go so far that it touches the child who will become the monster? And what about that child’s own experience of having things done to him? As my critic friend pointed out, the child MJ grew up in an exploitative milieu. That exploitation travels through time too—travels forward. We call it causality. We yearn for a reason behind the terrible acts of men, and we rest in the explanation. We tell ourselves: MJ’s crime grew out of his exploitative childhood; Polanski’s crime

...more

In any case, we’re left, like it or not, with the stained work. The deed colors all it touches. (And at the same time, “I Want You Back” sounds as good as it ever did.) None of us want to know the things about Michael Jackson that we know. We wanted to keep loving him. When the Leaving Neverland documentary came out, no one really even wanted to watch it. It was a dreary task we thought we ought to do. We felt we should witness the survivors and their stories. (But why am I resorting to “we”? Because it felt like a shared responsibility?) Too weary of monstrousness, of stains, for months I

...more

The problem is, we don’t get to control how much we know about someone’s life. It’s something that happens to us. We turn on Seinfeld, and, whether we want to or not, we think of Michael Richards’s racist rant. This movement toward knowingness began with the birth of mass media, grew in the last century, and has flowered in our moment. There is no longer any escaping biography. Even within my own lifetime, I’ve seen a massive shift. Biography used to be something you sought out, yearned for, actively pursued. Now it falls on your head all day long.

That’s not how it is anymore. Now it seems impossible to shake work loose from biography. We swim in biography; we are sick with biography. This is a modus vivendi for contemporary artists—an artist like, say, Harry Styles must maintain whatever mystery he can in the avalanche of information that has been shared about him over the past decade. Indeed, what mystery he possesses comes from our knowledge of the wondrous fact that there’s an actual person, a soul, hidden somewhere in the midst of all this information. This biographical reach extends to older artists as well. Now my Beatles-mad

...more

very phrase “cancel culture” presupposes the privileging of biography—a whole idea of culture built on the fact that we know everything about everyone. We live in a biographical moment, and if you look hard enough at anyone, you can probably find at least a little stain. Everyone who has a biography—that is, everyone alive—is either canceled or about to be canceled.

The stain—spreading, creeping, wine-dark, inevitable—is biography’s aftermath. The person does the crime and it’s the work that gets stained. It’s what we, the audience, are left to contend with.

A truism of our moment in history is that we live in the time of the fan. As biography rises, as its shadow called cancel culture escalates, fan culture also ascends. In the accelerated endgame of the age of mechanical reproduction, the fan is both debased and exalted. The work, designed to be reproduced, needs a large body of consumers. The “I” of the audience must become “we” in order for the market to work. As fans, we are crucial and yet not special. We are never alone; we are in a crowd. Our tears for the Beatles were always collective tears.

In this construction, obsession has a very specific function: to indicate our special status as the most intense appreciator of this particular thing/work/item. It means I am a fan, a superfan, an intergalactic fan, I am verily defined by this thing, it is my personality, it is me, I am it. What you like (i.e., what you consume; i.e., how you participate in the market) is not just more important than who you are: the two things are one and the same.

Obsession, real obsession, is not how you feel about labradoodles or Cool Ranch Doritos or even something truly great, like the poems of Richard Siken. Real obsession has tendons and guts and, and, and consequences. This new usage wants to steal the stakes of real obsession, and apply those stakes to something consumed. As a dedicated obsessive, I resent this!

The importance of our relationship with the artist’s biography is reaffirmed everywhere and all the time. Its signal quality is intimacy. The knowledge we have about celebrities makes us feel we know them. We feel we have the right to some intimate access to them. This feeling, I’ve observed, has only grown with time. Every year we are on the internet, we grow more enmeshed with public figures. The phrase “parasocial relationship” is a previously somewhat obscure sociological term that has been batted about the internet with greater and greater frequency—a spreading usage reflecting the

...more

We now exist in a structure where we are defined, in the context of capital, by our status as consumers. This is the power that is afforded us. We respond—giddily—by making decisions about taste and asserting them. We become obsessed with this thing, mega-fans of that. We act like our preferences matter, because that is the job late capitalism has given us. And here’s the funny thing—our choices and our preferences do matter, because something has to. Our selves are constructed from the shitty stuff of consumption, but we remain feeling people nonetheless. We feel things about people who don’t

...more

The problem with broadcasting, or with art, is that the flow only occurs in one direction. From the speaker to the receiver; from the artist to the audience. Telepathy, perfect union, is what we seek. Art—unlike broadcasting or the internet—becomes a meaningful stand-in for that union. The artist undergoes the rigor of making, and that creates the conditions for the audience to consume. The audience member sets aside her own ego, her own self, and participates in the dream built by the artist. There is a right relationship there—the relationship takes place on the page or the canvas.

...more

This dynamic makes the stain more destructive—the more closely we are tied to the artist, the more we draw our identity from them and their art, the more collapsed the distance between us and them, the more likely we are to lose some piece of ourselves when the stain starts to spread.

Reading has always been a one-way communion, but the kids in question solved that by talking back—to each other. They wrote endless fan fiction, reams and reams of it. They created their own art in response to Rowling’s work. They gave birth to a Potter-centric DIY movement where they were in artistic conversation with the books: I took my kids to Harry and the Potters shows—the band that founded “wizard rock” or “wrock”—and to live performances by Potter Puppet Pals, an online parodic series spinning off from the books.

The notion of belonging to a club—the notion of having been sorted—tied these children and young people together in shining bonds of connection. They reached each other box to glowing box throughout the night. This is a common story for us all, of course. We’re doing our best to practice telepathy, living up to the legacy of Alexander Graham Bell. But for these kids—especially these queer kids—the Harry Potter fandom was an intensified kind of identification, and it took place in an imagined world whose geography was as real as—realer than—that of the world where they lived.

The backlash across the internet was a great fury. Many of the former Potter kids were trans and they were rightly very angry. But underneath the fury was a deep sadness; the sadness of the staining of something beloved. Rowling’s tale of a place where otherness was accepted didn’t in the end include them.

Some of these children grew up to be adults whose dreamscape was taken away from them. Did they lose an imagined landscape where great swathes of their childhoods had been spent? I’m picturing a hillside, strip-mined.

The threat of being shamed lurks at the edges of all of internet life. What role does shame play in this dynamic between fan and fallen artist? Shame is noun and verb; it’s something I can feel inside myself, but it’s also something I can do to you. When we love an artist, and we identify with them, do we feel shame on their behalf when they become stained? Or do we shame them more brutally, cast them out more finally, because we want to sever the identification? Maybe shame is the ultimate expression of the parasocial relationship. Our emotions, collapsed together with those of the artists we

...more