More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Here’s a thing I believe about people my age: we are the children of Hogwarts, and more than anything, we just want to be sorted.

I was being wooed again.

Greatest among us are those who can deploy “my friend” to total strangers in a way that is not hollow, but somehow real and deeply felt; those who can make you, within seconds of first contact, believe it.

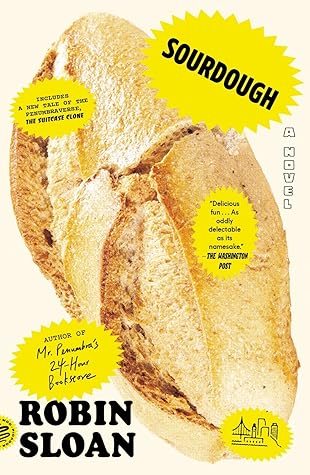

That bread was the secret of the whole operation. Beoreg baked it himself every day. • That bread was life.

The group around my table became my first shaky scaffolding of office friendship.

Anton, a sales associate burdened with a deeply unfortunate Bluetooth earpiece;

During a lull in the conversation around the table—they were many; we were awkward—I told my comrades in slurpage the sad news about Clement Street Soup and Sourdough.

We would solve everything else before we solved the egg problem.

I activated the standard suite of office chaff: left a data sheet on my desk, opened to its third page, seemingly mid-consultation, and draped my jacket artfully across the back of my chair, indicating that I hadn’t left the office—never that—but was only attending a meeting or crying in a bathroom. Normal stuff.

I HAD MOURNED MY LOSS and slurped my Slurry and was buffering a dark serial drama through my slow internet connection when I heard a knock on the door, light and confident. I knew that knock.

LET ME JUST ESTABLISH where I was at with the whole cooking situation.

We possessed no stock of recipes, no traditions, no ancestral affinities. There was a lot of migration and drama in our history; our line had been broken not once but many times, like one of those gruesome accident reports, the bone shattered in six places. When they put my family back together, they left out the food.

You would expect a vegetarian, perhaps, to eat vegetables; you would be disappointed. There was never on my tray a single tuft of green.

Before I was the number one eater at Clement Street Soup and Sourdough, I was a very familiar face at the Whole Foods salad bar on West 10 Mile. My creations tended to go heavy on croutons. One day, a single chicken tender found its way into the nest of lettuce. It was delicious. So closed a brief and disastrous era.

If there was a spectrum of spaces defined at one end by my barren apartment, this marked the other extreme. Every single surface told a story. A long one. With digressions.

She had once run a cheese shop at the base of the hill, and her taste had not grown less discriminating; she served us the stinkiest cheese I have ever been offered at a casual gathering. Nibbling with varying degrees of enthusiasm were also:

Compaq Lois, who had been a marketing executive at that company in its boom years. Her wrists dripped with bracelets and chunky bangles, all gold; they piled up onto her forearms.

She looked like a Valky...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I needed a more interesting life. I could start by learning something. I could start with the starter.

He was out there learning, in his words, “to bake without dry yeast, without desiccation, without death.” Well, sure. Nobody wants death bread.

The internet: always proving that you’re not quite as special as you suspected.

There were detailed instructions. I love detailed instructions. My whole career was detailed instructions. Precisely specified actions, executed in order. A serene confidence settled over me.

The loaf had a face. It was an illusion, of course. Jesus Christ in an English muffin. It’s called pareidolia. Humans see faces in everything. Even so, the illusion was … compelling. This face was long and twisted,

wide-eyed and openmouthed, Edvard Munch–like. Where the crust cracked, it formed furrows in the face’s brow, lines around its howling mouth.

That loaf of bread was the first thing I’d ever prepared myself that did not come out of a box with instructions printed on the side.

The twisted face in the crust was forgotten as I carved and ate, carved and ate, until the whole loaf was gone.

If I wanted to share this miracle—and I did—it would have to be with people who knew me.

Garrett operated at a level of abstraction from food that made me look like Ina Garten.

He, like me, had never before considered where bread came from, or why it looked the way it did. This was us, our time and place: we could wrestle sophisticated robots into submission, but were confounded by the most basic processes of life.

I was drunk and tired and happy. More than happy: delighted. Proud of myself—not just for making the bread, but for sharing it, and for making a few friends, even if they were all programmers and Loises. Maybe programmers and Loises are all you need.

I wish I could say the moment was hazy or dreamlike, but I was sharp with the battle-readiness familiar to all humans of all eras awoken by strange noises in the night.

IT’S A MESS when strange events smack into the windscreen of a resolutely rational mind.

Cornelia was a highly strategic pawn in the on-demand delivery marketplace.

Baking, by contrast, was solving the same problem over and over again, because every time, the solution was consumed. I mean, really: chewed and digested. Thus, the problem was ongoing. Thus, the problem was perhaps the point.

In every legend of the underworld, there is the same warning: Don’t eat the food. Not before you know what’s happening and/or what bargain you’re accepting.

Maybe that was my great weakness: if a task was even mildly challenging, any sense of injustice drained away and I simply worked quietly until I was done.

The depot was wreathed in gentle effort. It percolated.

I rose earlier than ever before and experienced a portion of the morning that was new to me. I heard the chirping of unfamiliar bird species—negotiations that had, until now, been concluded long before I woke.

Carl offered me coffee from a family-size thermos. It was just the two of us crossing the bay, and when the fat little boat puttered below the bulk of the Bay Bridge, I felt like we were astronauts in transit across the back side of the moon.

I have come to believe that food is history of the deepest kind. Everything we eat tells a tale of ingenuity and creation, domination and injustice—and does so more vividly than any other artifact, any other medium.

“Here’s my theory, honed over decades of bullshitting to myself. This starter, it uses music as a kind of … synchronization. It helps the little yeasts and whatever-elses to do the right things at the right times. You’ve gotta be careful, though.”

When Naz used his espresso machine, it was musical: clack of portafilter, hiss of steam, gurgle of milk, clink of saucer. When Anita worked her cricket flour into dough, she stared into space, thinking with her hands. That’s what I wanted to achieve. Even Jaina Mitra: when she shuttled samples between her great microbial menagerie and the DNA sequencer, her fingers and feet moved of their own accord. She was elsewhere, gaze clouded, brain churning. She could have done it with her eyes closed. That, of course, was it.

The shiver of pleasure that ran through the assembled vendors was so intense I felt it like a rattling gust. They believed the fish. The fish was their prophet.

Until that moment, I hadn’t realized how much I cared about the opinion of an anonymous benefactor who sometimes inhabited the body of a painted fish. But I did.

I felt the disorientation of a generous offer that in no way lines up with anything you want to do: like a promotion to senior alligator wrestler, or an all-expenses-paid trip to Gary, Indiana.

“I think … my starter needs a warrior spirit,” I said. “It has a warrior spirit,” he said. “It was born with it.” “Then what’s the problem?” “You need to give it something to fight.” “Like what?” “A rival. Another culture. Something from Big Sourdough.” He paused. “Is there such a thing as Big Sourdough?”

He gave Jaina Mitra a feather-light hug, then offered his hand to me. Taking it, I encountered a palm of extraordinary dryness.

“I just want everybody to be healthy,” Klamath said. His bulldozer enthusiasm faltered; I detected a note of weariness. “We should be way past this already. I want people to have time to do the things they want, rather than work to make money to buy food, or scrounge around in the kitchen.”

It was a fungal party hellscape.

I should have known Mr. Marrow was the kind of person whose headband matched her top.