More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

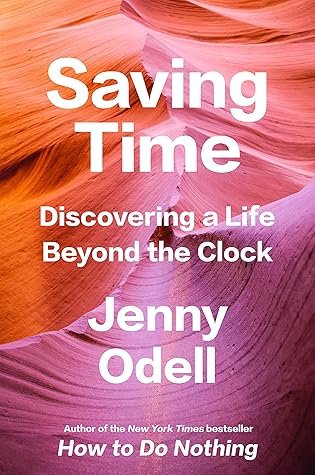

Jenny Odell

Read between

June 30 - July 9, 2023

In her introduction to the book, James describes all the time that goes into making the kind of time that can be sold for a wage: The ability to labor resides only in a human being whose life is consumed in the process of producing. First it must be nine months in the womb, must be fed, clothed, and trained; then when it works its bed must be made, its floor swept, its lunchbox prepared, its sexuality not gratified but quietened, its dinner ready when it gets home, even if this is eight in the morning from the night shift. This is how labor power is produced when it is daily consumed in the

...more

By imputing value to women’s work and thus to care, Wages for Housework sought a society in which care and collective liberation, not personal ambition and brutality, would be paramount—for everyone, and a benefit to all. In her discussion of the Wages for Housework movement, Kathi Weeks astutely emphasizes its use of the demand: not so much a plea for money as an unapologetic statement of power and an expression of desire. The demand is a total rejection of a situation that divides, per Braverman, “those whose time is infinitely valuable” from “those whose time is worth almost nothing,” a

...more

Some of those frustrations, whether you are advantaged or disadvantaged, include the following: having to sell your time to live, having to choose the lesser of two evils, having to say something while believing in another, having to build yourself up while starved of substantive connection, having to work while the sky is red outside, and having to ignore everything and everyone whom, in your heart of hearts, it is killing you to ignore.

Hoping and walking have preoccupied me the past dozen years, but I had to travel a long way down those two paths to realize that they were the same path whose rule is motion, whose reward is arrival in the unanticipated, and whose very nature is in contrast with the tenor of our time, a time preoccupied with the arrival and the quantifiable. Many love certainty so much more than possibility that they choose despair, itself a form of certainty that the future is notable and known.

sociologist Richard Sennett has observed that “routine can demean, but it can also protect; routine can decompose labour, but it can also compose a life.” It can be the construction of ritual, the way that the rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel called the Sabbath “a palace that we build in time.”

Would it be possible not to save and spend time, but to garden it—by saving, inventing, and stewarding different rhythms of life? And wouldn’t this simply be an acknowledgment and use of the chronodiversity that already exists for all of us on some level, individually or communally?

Saying it meant that you could take time and give time, but also that you could plant time and grow more of it and that there were different varieties of time. It meant that all your time grew out of someone else’s time, maybe out of something someone planted long ago. It meant that time was not the currency of a zero-sum game and that, sometimes, the best way for me to get more time would be to give it to you, and the best way for you to get some would be to give it back to me. If time were not a commodity, then time, our time, would not be as scarce as it seemed just a moment ago. Together,

...more

A discussion of disability naturally brings up questions about what and whom we accommodate. “How long does it take, or should it take, for a body to move through the world, the forty-plus-hour work week, the demands of caregiving for ailing parents, the daily commute of the body with its changing needs over the life span—a pregnant body, an aging one, a body in recovery after a bad injury?” Hendren asks. “Is the clock of industrial time built for bodies at all?” In proposing a different kind of clock, crip time unsettles (as Sharma would say) what time means. Heterogeneous, nonstandard, and

...more

Disability highlights something that is true for all of us: No matter how independent and fit we may feel, we are not simply alive but, rather, kept alive—against odds that some people are nonetheless privileged enough to ignore.

Social death is related to physical death in that the former puts one at greater risk for the latter, but social death also concerns a broader phenomenon of “death.” The border between living and dead, for instance, becomes fuzzier when “some subjects never achieve, in the eyes of others, the status of the ‘living.’ ” The socially dead take on a taboo quality that is at one with the American inability to think or talk about death, generally, or to reckon with its historical past.

A life sentence represents one of the most extreme examples of rendering someone socially dead, by creating a person with no future.

People and things are alive when we become alive to one another. To regard someone is a balancing of power, an agreement not just to shift one’s center of gravity, but to admit to two centers.

The philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti writes that, in a state of complete attention, “the thinker, the center, the ‘me’ comes to an end.” This supposed emptiness makes way for so much more, as “it is only a mind that looks at a tree or the stars or the sparkling waters of a river with complete self-abandonment that knows what beauty is, and when we are actually seeing[,] we are in a state of love.”

Because skyscrapers tend to be built where hard rock is close to the surface, the shape of the Manhattan skyline can be read as a translation of the underground presence of Manhattan schist.

Compared to chronos, kairos sounds like the domain of those wayfarers who knew that time is inseparable from space and that every place-moment demands close attention, lest you miss your opportunity. It’s not that you can’t plan, but that the time in the plan doesn’t appear flat, dead, inert. Instead, in the “meantime,” you wait with your ear to the ground for patterns of vibration that will never repeat themselves. Faced with flatness, you look for an opening. When it comes, you take it, and you don’t look back.

This passage occurs in the preface, where Arendt describes the moment after the unexpected fall of France to the Nazis in 1940. European writers and intellectuals—“they who as a matter of course had never participated in the official business of the Third Republic”—were suddenly “sucked into politics as though with the force of a vacuum,” into a world where word and deed were inseparable. Arendt argues that this created a public intellectual realm that, only a handful of years later, would collapse as they all went back to their private careers. Yet those who participated remembered a

...more

In this context, doubt is actually the valuable thing, the thing we want to seize. But encountering freshness and agency in this way, Arendt wrote, required someone to hold their ground “between the clashing waves of past and future.” Otherwise, you’d get flattened by certainty: The past would crush you with tradition, and the future would crush you with determinism. Hence the importance and fragility of the “gap” (another term for “non-time”) in the title of Arendt’s preface, “The Gap between Past and Future.”