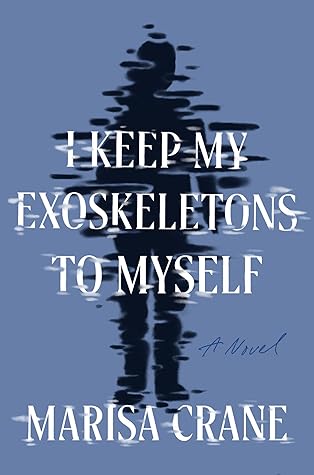

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Upon confronting the car seat, I realize that it had been your job to learn how to use it.

You aren’t waiting for us when we get home. You aren’t lying in bed reading. You aren’t cooing in Mischief’s fluffy face. You aren’t sifting through the mail, perusing the circulars for sales. You aren’t, against your better judgment, making an afternoon coffee. Suddenly, all this unoccupied space. I want to get blackout drunk for months on end. Yes, that’s what I want. I want to sit in my own filth and like it.

When you got your new teaching gig, I peeked over your shoulder at your life insurance policy and said, Not bad, smirking a little. I’m never letting you make my morning coffee again, you said. I remember feeling a little insulted that you thought I would use something as impersonal as poison.

Matthew liked this

According to you, the photographer had looked bewildered when you’d chosen that print. Apparently, he’d been trying to sell the print for ten years. He didn’t understand why no one had wanted it; he said it was the best photo he’d ever taken.

Tomorrow, I decide, will be better. Tomorrow, I will recover from today.

Pop Quiz: Q: Can you name an emotion other than lonely? A:

We held each other’s hands tightly. The same hands we sometimes dropped in public when we felt unsafe—we had that privilege unlike so many others; whiteness meant we could remove our otherness like a sweater if we wanted. We could walk five feet apart and temporarily become gal pals.

“Yesterday a man told me I sounded like I needed a good fucking,” I say. “What does that even sound like?” “You’re listening to it, baby,” I laugh.

When you finally got pregnant, it was brilliant, it was magic, it was like finding a secret tunnel between dimensions. But you—we—had a miscarriage at sixteen weeks. I’d never seen you cry so hard. You took a week off work and curled up in bed. You spent most of the time staring at the wall or ceiling. I tiptoed from room to room trying to find somewhere to put my body. It took me a few days, but I finally broke down one morning making eggs and sausage. I don’t know what it was about breakfast that pushed me over the edge, but it did. I think it’s because I realized breakfast is for families.

“The human brain is nature’s biggest mistake. An honest mistake, but a mistake, nonetheless. Nothing that has happened should have happened.”

“I think I know where this is going, Kris.” “No, you don’t. I want to ask people if they ever feel sad. Like, I know they do, but I want to hear them say it.” Alice points her pen at me and smiles. A breakthrough. “That’s because you want to know you’re not alone in your grief. Perfectly normal,” she says, jotting things down, perhaps writing “Perfectly Normal” under my name. I don’t see her again because she made a good point, and I wasn’t there for the good points.

When my cousin was released from prison, he was never able to find a job again. Every time a potential employer saw his criminal record, they stopped calling. I’ve been forever marked, he told me a few days before he overdosed. And to think, we thought the prison system was corrupt, but the reality is, it was just preparation for what came next.

I imagine that the kid winds up forming an unhealthy obsession with suicide. She spends a lot of time asking why someone would do such a thing, and I spend a lot of time shocked but grateful that she doesn’t understand wanting to die. In this scenario, I say, Your other mother would never do that to us, over and over, even though the kid hasn’t asked, not once.

KRIS’S TREATMENT PLAN Daily Progress Note: List goals as notes on treatment plan. Progress toward goal: Regression = 1, Consistency = 2, Improvement = 3. 1. Kris will learn to recognize life’s joyful moments as they are happening. Rating: 2 2. Kris will manage her frustration in positive, socially acceptable ways. Rating: 2 3. Kris will remain so busy that she cannot possibly think about Beau’s death, the state of the country, the kid’s future. Rating: 1

The kid sits in timeout in her room while I sweep up the glass. I’ve never given her a timeout before, so neither of us seems to be one hundred percent certain how it works. But after she stomped into her room, I hadn’t wanted her to have the last word, so I knocked and said, “Timeout activated!” An hour later, when I knock on the door again, the kid says, “Excuse me, your timeout isn’t up yet, Mommy.” “It seems there’s been some miscommunication,” I say. “You haven’t had enough time to think about what you’ve done,” she says, but as she says it, I can hear her creeping closer to the door, at

...more

Your mom likes the pictures of the kid. She says the kid looks just like you. I like talking to your mom because she’s the only person who seems to understand that time doesn’t exist, and that it’s just as hard today as it was that day in the hospital.

My father insists that he take the three of us out to lunch to meet his new girlfriend. What I know so far: her name is Audrey, they’ve dated for six months, she likes online shopping and romantic comedies, and she is at least twenty years younger than him. “I’m not sure what this has to do with me,” says the kid on the way there. “Pretending to be happy for someone you love is a key life skill,” I lecture. “Or we could actually be happy for him,” says Michelle. “You make a point. Not a particularly good one, but a point.”

I don’t know what’s wrong with me, but I can’t shake this feeling of impending doom. What I’m trying to say is—I’ve never been afraid of anything more than I’ve been afraid of my own happiness. But I want it, oh I want it. Something tells me it isn’t happiness without fear. This small fact keeps me breathing and sleeping.

There was that time I asked Siegfried what we should give criminals instead of shadows. I didn’t necessarily think we needed to bring back prisons, but I didn’t know what we were supposed to do with the people who’d committed serious crimes. Real crimes, not Kris crimes, not the kid’s crimes. Not Siegfried crimes, or so I’d thought at the time. “Forgiveness,” he said. “And what if they don’t deserve it?” “What is this talk of deserve? What does that word even mean?” he said.

Here’s the thing: when an insect grows too big for its exoskeleton, it sheds it, a process known as molting. This may sound benign, but insects cannot breathe while molting. They must stop eating and lie very still. Completely incapacitated, they are vulnerable to a predator attack.