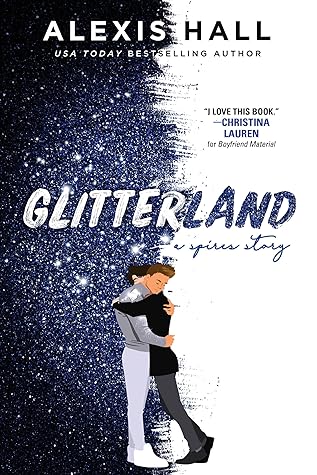

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

In the past, the universe is a glitterball I hold in the palm of my hand. I am the axis of the world. In the past, I am soaring, and falling, and breaking, and lost.

“What the fuck are you doing?” demanded Niall. “Are you fucking insane?” He was probably hurting me, but I was too far from myself for it to breach the numbness of my skin. “Well, yes. I have a note from my doctor.”

Depression simply is. It has no beginning and no end, no boundaries and no world outside itself. It is the first, the last, the only, the alpha and the omega. Memories of better times die upon its desolate shores. Voices drown in its seas. The mind becomes its own prisoner.3

All sense, all judgement, overthrown by an h-dropping, glottal-stopping glitter pirate, and I didn’t have to care.

And a strange, inexpressible sorrow for the shining moment that is never more than a moment.

“Speaking of service,” she added, “I’ve got a dress fitting. Don’t suppose you want to come with me?” I really did not. “I’m not that kind of gay.” “Dammit. Can I do a part-exchange?” “A homosexual is for life, not just for Christmas.”

She was pretty in what I thought was probably an Elizabeth Bennet sort of way: lively eyes, wicked smile.

The truth was, somewhere down the line, between the hospitalisations and the drugs, I’d somehow lost the cornerstone of humanity: the ability to pretend, to counterfeit the basics of social interaction, to smile when you didn’t feel like smiling, to seem like you cared about other people when you lacked the capacity to care about yourself.

“Do you know your plants are all like…dead?” I looked around. As a certified loon, I was always being given plants, and Darian was right: they were all dead. Very dead. I coughed. “Oh, yes, I’m the Green Reaper. I bring plants here to make them suffer.”

“In fiction, like life, there’s only ever the now. And the boundary between the real and the unreal is simply a matter of perception.”

He smiled. “Yeah. Reckon you could read the phone book and make it dirty.” I ran my hands up the inside of his splayed, denim-coated thighs, wishing it was skin beneath my palms. “This is the news at ten,” I whispered. “Politicians are predicting hard times ahead.”

There was little I feared more than happiness, that faithless whore who waited always between madness and emptiness. My moods, when they were not sodden with medication, could turn upon a tarnished penny; happiness was merely something else to lose.

I wished I could sleep. I wished I could stop thinking. But my mind has always been its own enemy.

“You know, for somebody who made such a fuss about being treated like a gentleman of the night, you’re remarkably eager to use sex to get what you want.” “Ha-ha, gentleman of the night. Lie-kit! But who said anyfing abaht sex? That was your mind in the gutter, mate.” “We are all of us in the gutter, but some of us are enjoying ourselves down there.”

Whatever I did, no matter how hard I tried to pretend otherwise, there was no respite from my limitations. I was my own cage. And I hated it. Hated myself.

It was like being in hospital again. Reduced from the first person to the third. From subject to object. I was disappearing into other people’s sentences. I wanted to speak, but I didn’t dare. I didn’t know how it would sound. Whether my voice would break. If I would be plausible. If I had the right to want anything at all. What use to the sane, after all, were the words of the mad?

I had never wanted death, merely cessation; unfortunately, sometimes, they seemed to be the same thing.

“I just wanted to fix you,” he said. “This is who I am.” I put my key to the lock. “I don’t need fixing.”

The impossible ouroboros of want and wanting, the twin pleasures of giving and taking, swirled together as richly as oils upon a canvas.

“Darian.” “Babes.” He wasn’t getting it. I was a muddle of longing, frustration, and pain, my mind scattering like seabirds. “I’m not a fucking plural,” I snapped. “What?” I pointed at myself. “Item: one babe.”

“Yes, death is so very ugly. They don’t tell you that. But it is.”1

“Well, not even managing to kill yourself properly is a bit of competence nadir, don’t you think?” “I dunno, I reckon it’s pretty ’ard. I mean, being alive is like a…whatjamcallit…like blinking, y’know, just summin you do wifout ’aving to fink about it.” I shook my head. “For most people, perhaps. For me it’s a daily commitment I sometimes don’t feel like making. But I hate that I tried. And I hate that I failed. This doesn’t represent some beautiful moment in which I chose life. It’s a fuckup, pure and simple. If it was up to me, I wouldn’t be here.”

“Barthes said language is a skin. I’m sure he never meant it quite this literally.”2 “Who’s Barfs?” “Barthes. French literary critic. Gay. Perhaps overly fond of his mother. Prone to nervous breakdowns.”

I wanted—I needed—Somebody to save me. But how could you be rescued from yourself?

“I’m not here because I’m broken. I’m here because I’m whole. Difficult, potentially undeserving, but whole. And I don’t need you, I just want you. I want you”—my voice had gone embarrassingly husky—“so fucking much. And—” Another breath, another breath. “—maybe I love you. Or could love you. Or might love you. Or may come to love you.” There was a dizzy rushing in my brain, as though I was about to faint or have a nosebleed. “Or whatever.”