More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

A couple of days after her arrest, my mom appeared before a judge in an Israeli military court. My dad attended the hearing, shouting out words of support to her from the back of the courtroom. “Be strong!” he said. “You’re strong, and we want you to remain that way! We love you, and we’re all very proud of you!” Comforted by his encouragement, my mother smiled back at him and nodded reassuringly to let him know she’d be okay. I wasn’t there, but my father reported back the details of the day, and I was relieved to hear that she was doing well. His words boosted not just her morale but ours as

...more

In fact, out of 739 complaints filed by the Israeli nonprofit human rights organization B’Tselem regarding the death, injury, or beating of Palestinians, only 25 resulted in the implicated soldier being charged. Expecting our oppressors somehow to deliver us justice was a fool’s errand. The outcome would always be consistent with what the Palestinian people had experienced for decades: Israel can murder us, displace us, ethnically cleanse us, and usurp our land and resources—all with impunity.

At eleven years old, in the span of minutes, I was teargassed in my own home and shot in my hand. But despite this terrible misfortune, I’m considered lucky that my house was only one story, and I was able to evade the fog of tear gas relatively quickly. Others weren’t so lucky.

when the trauma subsided, a transformation occurred. The children now understood that being indoors was just as dangerous as, if not more dangerous than, being outdoors. At least outside they could see where the tear gas was being fired and run the other way. After that, Janna and many of the other children began joining the marches. But it wasn’t just a question of relative safety: Being attacked in your own home ignites a strong determination in you to want to defend yourself. You summon a type of courage you didn’t know you had, and as you grow, that feeling of courage grows, too.

But the fact remains that Janna, just like the rest of us, should have been busy playing, not resisting. No seven-year-old should ever feel she has to shoulder the burden of documenting the human rights abuses taking place in her own backyard. We shouldn’t have to grow up seeing our parents arrested and fearing they could be shot or killed at any moment. Nor should we children be able to know instinctively whether the blasts outside our doors are from tear gas, sound grenades, rubber bullets, or live ammunition. And yet, we all acquired this skill even before we hit puberty.

So, to return to the question our parents are always asked, about why they allow their children to protest: It is the occupation that forces the children to go out into the streets.

THE DEATH OF MY uncle was the straw that broke the camel’s back. After that, it wasn’t just a case of my willingly joining all the marches; now they became the highlight of my week. Despite the inherent risks posed just by going out and protesting, I ultimately felt I was doing something productive, if not cathartic. Because I refused to remain quiet or feel defeated, my conscience was at ease. Going out and expressing myself by telling the soldiers they were not welcome on my land somehow filled me with optimism and hope. It made me love life even more. Aside from fulfilling my patriotic duty

...more

My parents instilled the notion in me and my brothers that if we didn’t do anything to benefit our homeland, then we didn’t do anything to benefit ourselves. If I was successful in life but my success didn’t help Palestine, then it wasn’t truly a success. They planted this seed in us while we were very young, but even if they hadn’t, everything I had witnessed from a young age would have been enough to make the liberation of Palestine the main goal of my life. Still, as our popular struggle continued, so did the sacrifices we were compelled to make. The arrests, night raids, shootings, and

...more

Sometimes, within just minutes of our demonstration starting, the soldiers would open fire on us without any warning. They also began deploying snipers, who fired live .22-caliber ammunition at protesters, aiming for their legs. We all knew they were aiming for a particular nerve in the lower leg that can leave a victim paralyzed.

“Thank you for your tears,” I began. “But I don’t want your sadness. Nor do I want your money. Please save that for the people in your own country who need it. My people have dignity and don’t want your pity.

We want you to see us as the freedom fighters we are, so that you can support us the right way.” I went on to explain how important it was for them to show their solidarity by boycotting Israel politically, economically, and culturally.

We each had a part to play in our generation’s uprising against the apartheid and injustice that had deprived us of even a single day of freedom in our lives. We hadn’t inherited any victories in the fight against Israel, only the defeats our parents and their parents had suffered. Our role was to challenge those defeats,

An unspoken rule at these clashes was that the Palestinian guys weren’t allowed to wear long shirts, and whatever shirts they wore had to be tucked into their pants. They did this to distinguish themselves from the undercover Israeli agents, or mista’rabeen, who dressed in plainclothes to disguise themselves as Palestinians in order to ambush and arrest us. They’d even wear kuffiyehs to try to fully assimilate with us. What often gave them away, though, was that they pulled their shirts down over their waistbands, to conceal the guns they’d hidden there.

Unless you’ve experienced a foreign army occupying your land, imprisoning your parents, killing your loved ones, and shooting you and virtually everyone you’re related to, you’ll have a hard time understanding the rage with which I was overcome—seeing the entitlement of these soldiers as they walked around our property like they owned it.

A recent favorite pastime of ours was to broadcast live on Instagram, which was a fairly new feature at that point. My page was public, with six thousand followers, making it our preferred account, the one that would get the most engagement.

he paused and drew in a deep breath. “I think they might arrest you.” It feels silly to admit now, but in that instant, my initial reaction was one of sheer relief: I had dodged the potential bullet of my father grounding me. I mean, of course I didn’t want to go to prison, but in that second, I was thanking God I wasn’t in trouble with my father anymore.

I had received a few messages about the video when I was at the hospital awaiting news of Mohammad’s condition, and I understood that it had circulated a bit, but not in a significant way. It didn’t feel like a big deal. After all, this was by no means the first video capturing me confronting Israeli soldiers. At that point, plenty of them from over the years had spread way more intensely than this one. I didn’t think my latest altercation with Israeli soldiers was anything special or unique.

I had grown up internalizing the idea that it wasn’t a matter of if I’d be arrested by the Israeli army, but when. And that when was now. But strangely, I wasn’t afraid. It’s hard to explain the sudden strength that overpowered me in that instant. Perhaps it was the years of anticipation of this moment that had eliminated any fear in me. Instead, this felt like a challenge—yet another standoff between me and this foreign occupying army. I wanted to laugh in the officer’s face.

Show us your arrest warrant!” my mom demanded. “There is none,” the officer said. This wasn’t surprising. There’s never an arrest warrant.

At this point, the entire house was flooded with soldiers. All I could see in every direction were green helmets. You’d have thought this was the home of a terrorist with explosives who was planning a major attack, not that of a five-foot-tall sixteen-year-old girl who hit a soldier with her bare hands in her own front yard.

“I want to say a proper goodbye to my family,” I told the soldier who had handcuffed me. She ignored my plea and instead grabbed my right side while another female soldier grabbed my other arm.

We’d sit on plastic chairs huddled around a hookah, smoking and sipping mint tea while eating up their tales of being arrested. Other families in other places might sit around and talk about vacations they took or movies they watched. We sat around and talked about spending time in Israel’s prisons.

All the stories I had heard growing up, from my father, uncles, brother, and cousins, about what to do while being interrogated had primed me for this moment. I thought specifically of my father’s story of the interrogation that nearly killed him in 1993, years before I was born, when Israel falsely accused him of killing an Israeli settler. That interrogation was so brutal, and my father’s injuries so severe, that Human Rights Watch documented what occurred. I’d heard my father retell the story many times throughout my childhood.

Instead of being at home with your family, you’re here in handcuffs. What a pity.” I’d start laughing in my head, thinking, Given everything I’ve endured in my life—including seeing my relatives killed and maimed by your forces, getting wounded myself as a young girl, having my parents repeatedly arrested, and being denied any semblance of a normal childhood—you want me to feel bad about this?

Once the plea deal was presented to the judge and the hearing was concluding, I addressed the courtroom. I decided to speak the only words that needed to be uttered in that setting: “There is no justice under occupation, and this court is illegal.”

my thoughts and fears about how I’d manage to reintegrate into my former life were incessant. I stressed out over how I’d speak to my family and friends. We had been essentially estranged for nearly eight months, with no mode of communication. I’d become an entirely different person during that time,

They asked what I had learned in my time behind bars. I told them I had gained a better understanding of our cause and of the right way to fight for it and that I had learned the virtue of patience and how to be in a group.

They wanted to know what I had missed most. I told them I had missed my family more than anything. And second to that, I had missed being able to look up at the sky and see the sun and moon and stars rather than barbed wire.

They asked if my time behind bars had made me more afraid of Israel or had subdued me in any way. I told them that the efforts of the prison administration to kill my spirit had failed. The blow that doesn’t kill us only makes us stronger. They asked how I felt about the unprecedented level of my newfound fame. I told them I’d never sought nor enjoyed the limelight, but that it was an honor and a lifelong dre...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

They asked me how I believed the Palestinian people ought to resist. I told them there were many ways of resisting—whether by writing poetry, speaking out, throwing stones, or making art—but at the end of the day, it was up to the people to decide the right path forward for them. And of course, in virtually every interview, they asked me if ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Many others singled out my appearance as a blonde with blue eyes as the reason behind the disproportionate level of media coverage I was getting: It all boiled down to white privilege, they suggested. But I was among the first to say that my appearance was a huge reason my case garnered international attention. It enabled white Americans and Europeans to look at me and see their own children. It allowed for a level of sympathy that otherwise might not have been there.

As a child, I used to look around at my family members and wonder why I looked so different. Why did I have this mane of blond hair that no one else had? After seeing how much the rest of the world fixated on it, I began to think that maybe it was a mask God had given me with which to make a difference.

The people who constantly complained “Why Ahed?” likely didn’t know all the hardships my village and I had endured, the losses we had suffered. They didn’t account for the fact that I’d been filmed confronting soldiers, and even featured in viral videos, since I was a young child; there were plenty more than just that one slap. Nor were they aware that while I was in prison, my father and a team of volunteers put in a lot of effort to communicate with journalists, activists, and leaders around the world to get my story out there.

I was invited to take part in a speaking tour across Europe, where I’d be meeting with various human rights organizations, activists, and leaders. I had been out of prison for only a little over a month by the time the tour was scheduled to begin and was already growing a bit weary from the pressure of having to constantly speak. But I knew the level of interest in Palestine—and the solidarity with Palestinians we were seeing—was rare, and I had to seize upon its momentum to further advance our cause.

Nothing built on injustice and might lasts forever. Eventually, the oppressed find a way to liberate themselves. May we all one day break free from our oppression and imprisonment. Until then, the struggle continues.

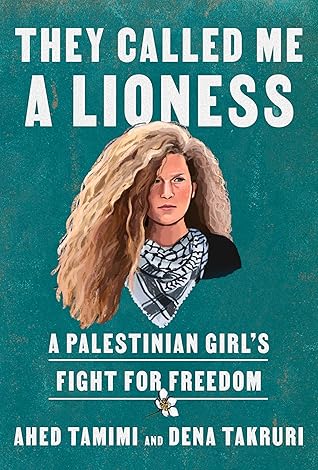

Finally, I thank everyone who reads this book and sees me as I wish to be seen: a freedom fighter.