More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

B- Asians who always lagged a beat behind, sold weed, and asked to copy my calculus homework.

This was before Black Lives Matter made being “radical” “cool,” when it was almost mandatory to be an untroubled liberal.

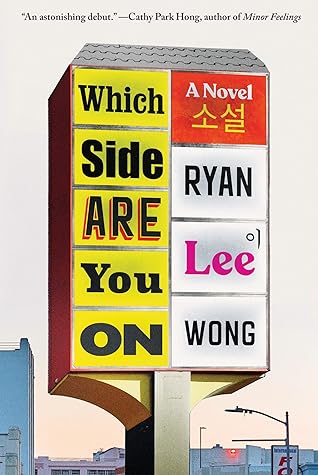

And so the few dozen of us counterprotesters began to sing that movement anthem at the top of our voices: Which side are you on, my people? The haunting melody that floated up and then, in the second line, fell in a mirror image of itself—Which side are you on—as if the brutality of the situation took away the question mark, gave you one line to make up your mind, so that by the second it was a demand.

We both thought CJ had made it when she got into Hah-bah-du, guaranteeing, at worst, a lifetime job of tutoring for a hundred bucks an hour—thought she could finally drop the stress that choked her with every test, every big paper during high school. But the release never came. The grind of getting into Harvard only gave way to staying afloat there: navigating the students who treated Harvard like one more playground guaranteed since birth, the secret societies they formed to hold the line between themselves and the Dorm Crew workers like CJ who got there early to scrub toilets, the professors

...more

I felt defensive, as if they were in the next room. “Tiff goes by they pronouns, Mom.” Mom blinked. “I don’t get all this stuff. In Korean, we don’t have pronouns.”

“Exactly,” Mom jabbed the air. “That’s the biggest challenge—figuring out your own people.”

It was an education in my own skin.

We’d found it, my penis: nothing special, nothing sexual, just something to be moved aside, the way you’d lift a rug to sweep the floor. It was a relief, actually, to let it be a lump of flesh.

Mom, CJ, and this man all demonstrated affection the Korean way: through hitting.

“By organize, you mean talk shit about white people on Twitter?”

My entire life was an experiment in communal praxis, and somehow my parents were surprised I’d ended up in activism.

“Which side are you on?” Dad nodded enthusiastically. “You know, that’s a labor song from the Kentucky miners’ strike.” Nothing energized him like labor history. “Then Pete Seeger recorded it. Now it’s being appropriated by everyone, including your movement.”

defunding the police.”

L.A.’s two biggest, swelling immigrant groups butting against each other, giving us the kalbi taco and the modern race riot.

Second, half the reason people join movements is to hook up with each other.”

That was L.A.: everything was hidden out in the open, tucked into strip malls so we could play that bourgie game in which the more obscure the strip mall was, the more exciting the find.

It was impossible to get just a haircut in K-Town: everything came with a side hustle of matchmaking or gossip. Now Mom was stepping in to protect me, a lioness afraid I was about to be caught in a love intrigue with her hairdresser’s daughter and she would later suffer the gossip through the K-Town vine.

If this continued, I would literally be, on the cellular level, a new person.

I hated participating in the gig economy, but L.A.’s architects left me little choice when they gutted public transit decades before I was born.

She was the Harvard kid who read Joyce but also smoked cigarettes and hocked loogies standing next to white Civics in parking lots. She had even attended a Korean megachurch until sophomore year, when she found Nietzsche. I’d found the term code-switching funny when I learned it in college: to me, it just described how my high school friends got through the day.

CJ groaned. “You sound like Adorno if he, like, worked out his ideas on Twitter.” “I’ll take that as a compliment?” “Ugh, who would want to be friends with Adorno? Sounds depressing as fuck.” “Horkheimer?”

Jane went up to a guy with a shaved head and hard, angular face—the kind of Korean guy I avoided in high school, the kind of bro Peter Liang reminded me of—and planted her mouth on his.

“So,” he said, “you’re at Columbia? You gonna be an I-banker, make some paper?” I chortled. Then I composed myself. “Sorry,” I said. “No.” Austin’s eyes narrowed. “Why would you spend all that money on Columbia, then?” I saw that we’d have to dive into a minihistory of the Gurley case, then talk about Asian Americans perpetuating anti-Blackness, in order to arrive, ironically, at an agreement that it wasn’t worth the money to continue my education. “I guess I wanted to get away from L.A. for a minute,” I said instead.

I leaned against the railing and almost saw the appeal of the dance floor, a mass of limbs polished red, blue, and gold by the lights: To lose yourself in the sweating and gyrating, an abandon built on unspoken racial exclusion, because wasn’t that our right as people who had been excluded ourselves? If you could ignore or deny that, it might even be fun.

“Because I should actually be sucking off you and your brilliant theories instead, right?” she screamed. “I’m fucking sick of you reading Twitter and saying the same shit everyone else is so you can feel superior—so you can ‘save’ me by showing me the truth.”

I was like a zombie, reanimated by chemicals, which was exactly why everyone drank coffee all day at their cubicles: to force their bodies into the repetitive motions that greased the machine, zombie originally a word for the eerie act of walking to and from work. CJ’s voice came to me, telling me to shut the fuck up, Adorno.

It seemed impossible that anyone would wish us harm, would find our Asian faces anything but unusual.

“Reed,” Mom steadied herself and her words came out smooth, like steel. “This is not your crisis. I want you to stop. I’m serious.”

The sense of victory would slip away if I accepted her apology.

the heavy philosophical shit CJ and I discussed over boba, beginning, in our clumsy, not-yet-Ivy-League way, to amass cultural capital.

“Right,” he said. “Unfortunately, turns out it’s hard to build a movement when you keep ejecting people for not being perfect.”

“You’re smart enough to know the difference between performing politics and living them.” “That’s not how it is anymore,” I said. “How you show up in the world is also how you change it. How you talk about the movement is the movement.”

I saw with revolting clarity how easy it was to cover the one thing that marked me as a target, because it was not my skin.

“Because I care about you, my son. And it’s just not worth it.”

There are times to fight and there are times to get home.”