More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 19 - September 14, 2023

I am not rewriting history. I’m using the same facts, figures, events and evidence as we’ve always had access to, combined with recent advances and discoveries. The difference is that I’m shifting the focus. The frame is now on female rather than male characters. Both perform in the narratives, and we can only truly understand one in relation to the other. This book is about individuals, rich in their complexity and fascinating in their variety. It is also about societies – groups of individuals working together and against one another, alongside a backdrop of shifting politics, economics,

...more

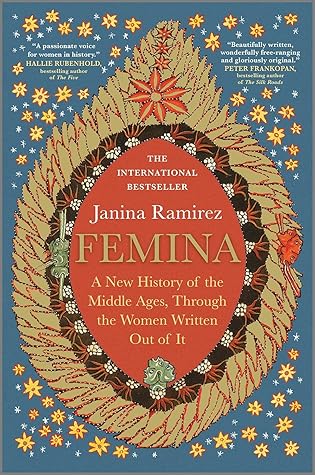

From the Reformation onwards, libraries were scoured for controversial texts. Various shorthand terms were used in catalogues to indicate which should be considered and potentially destroyed. Books were recorded as containing ‘witchcraft’, ‘heresy’ and ‘Catholic’ subject matter; the destiny of many of these texts is unknown, with the lists the only record of their existence. The title of this book – Femina – was the label scribbled alongside texts known to be written by a woman, so less worthy of preservation.

She gained respect in Mercia during her lifetime, even if the Wessex version of history was the one that spread most widely. A Worcester chronicler records she was ‘merciorum domina, insignis prudentiae, et iustitiae virtutique eximiae femina’ (a woman of prudence, justice and extraordinary strength of character).

To later Norman writers she was like an English Joan of Arc, a warrior woman who deserved fame. But when her story no longer served the dominant narrative, her reputation was eclipsed. Over the last three centuries, it is her father, Alfred, who has become a rallying point of national pride, held up as the exemplar of a great Englishman. But during her reign, and for centuries after her death, many recognised Æthelflæd as ‘more illustrious than Caesar’. She was a victim not of medieval prejudice, but of modern attitudes towards female leadership. Seeing her as her contemporaries did shows us

...more