More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It was not easy to trust a woman who had spent the week of the initial search for Wayne’s body lying face-up on the sofa, blasting Nina Simone.

I felt I was seeing her truly for the first time—not only the way we all come to see our parents as fallible humans, but also the particularities of her whiteness, the way she seemed to seek expression of her feelings only through black art.

I was too old for this and we both knew it. But my father didn’t scold me. He rolled the chair back from the oak desk and pulled me onto his knee. He ruffled my curls and kissed the top of my head, his lips saying, “Shh.” I was too old for this, too. I leaned back and rested my head on his shoulder and let my crying wash through me, staring blankly at the screen as he typed in search terms. I wish I’d paid more attention then to what he was searching for.

I wondered if, all this time, my mother had thought that she was the one saving me, not from guilt, but from the blame that she secretly held under her tongue, and that, if uttered, would cast me out completely, put me in a place where she could no longer love me. The world is never what you think it is. It can turn over and expose itself to be the exact opposite.

I decide to trick them, I take a tiny chunk of flesh from my nose piercing and place it in a bowl, Grandma Lu’s silver mixing one, and the shadow worms promptly gather inside it and form a tangled lump, like when you turn a pot of old spaghetti upside down, and the lump licks slickly with movement, the shadow worms weaving and unweaving and growing even longer and thicker, and I realize the chunk of flesh has been seeded, the worms are hatching from it, my flesh is their origin point and I’m

My latest therapist, Dr. Weil, had recently introduced me to a theory called “life span integration.” The premise is that you make a story out of your life. You plot it to give yourself a sense of continuity. In the therapy, you zoom in on moments of trauma—where the line broke or knotted or looped—and undo them, give yourself a before and an after. You try to convince yourself that you did in fact survive, that life kept on keeping on even after everything seemed to fall apart.

I hated that my mother had forced me to go to Savannah. It was a trap to make me do something I already wanted to do while she took credit for it.

Absurdly, I had assumed she would be wearing a suit or business casual, probably because I associated her primarily with her job as a lawyer. Josephina wore Birkenstocks, too, and a lot of jewelry—not the pricey, glittery stuff, but that carefully considered morass of metal and leather and string that signifies “Bohemian” for girls too sheltered to have shopped at street stands or flea markets. Josephina had no doubt bought her Bohemia from a store at the mall—sorting through a throng of fake silver chiming in the AC breeze—a store much like the one that I had just visited to get my nose

...more

I noticed that, as always, he started across the road without warning, without making sure it was safe for me. I decided not to play wounded and hustled after him.

My father had put on weight, but only in his belly, which was round and brown, adorned with a few gray hairs. If it could have spoken, it would have spoken in chuckles.

I pulled my knees up and used my fingernails to unstitch the black thread-ends of ingrown hairs. My father bit at his lips, tugging dry slivers from them with his teeth. Both of us would sting later when we went into the water. But this was habit, comfort, this shedding and grooming without judgment.

Vigil had come to feel like a younger sibling that I was both neglected for and made to babysit, like a new baby brother or a substitute for Wayne. That’s the thing about the bad math of this family: you can shift the numbers but there’s always something missing, something to carry.

“Good.” My father nodded with a frown-smile.

I meant that the fundamental grief, the hole out of which Vigil had sprung, was deceptive. A false hole, a black oval painted on the ground.

I confronted her about that first time but my anger always met Reena like water hitting ice: it either rolled off or froze into her own armor.

I generally don’t speak to people on planes. I’m the unfriendly woman gazing out the window, the wearer of earplugs, the bearer of novels, willful dozer, spurner of all contact.

I say nothing to this pretty white girl, who will waltz through life, I’m sure of it, who will be rescued at every falter.

“…mugged by a gang of snails and the turtle says to the cop, I don’t remember, it all happened so fast, an abomination when you think about it, the way they treat them, can’t believe this is what it’s come to, so what do you think it would go for now? In this market? The bubble’s gotta burst, right? The Animal, like in Marx? No, dude, like in the Muppets, I’m sure he’ll get the vote up in Napa, but, like, in the good part? But what kind of Japanese whiskey? Oakland is just San Francisco now, I work in tech, but what kind of weed gummies? Down in Palm Springs, yeah but that company ain’t gonna

...more

I see it in his face—the same exhaustion I saw in the girl out in the lobby. It makes me feel sort of tender for him.

He tugs a paw off his costume, uncovering a hairy but human hand, and shoves the paw in his pouch. He takes my arm. “Time to go.”

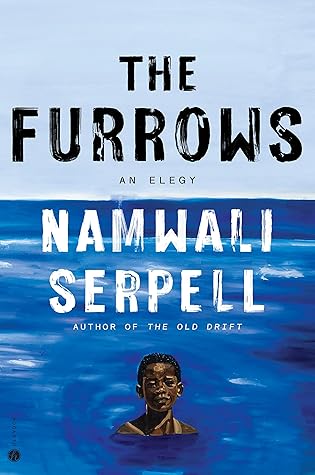

“Okay. One time, he told me, Time’s got grooves in it. A moment is a needle and time can skip like a record. I mean, listen, he was kinda nuts. He said things like, Time is like the ground, and when something big happens, it’s an earthquake, and when it’s little, it’s ripples, like those rows on a farm.” “Furrows.” She nods faster and the plane spasms and she laces her fingers in mine, tight. Everything grows warm and wide and round, a bubble around us.

I decline to hurry.

The last time we had sex, in the inn after the funeral, a Saturn-ring feeling like this took a loose lap around my mind, nearing my awareness, veering off, nearing again, until it came clear. Two sets of words, pressed against each other like competing palimpsests: Hit me. I love you. I think of your hip bones thudding against my sit bones and feel a snap of lust under my navel. Dr. Weil would say I’m fixated, that central x of the word like a stitch binding me to you. I’m in your thrall, those tall letters on either side of the word imprisoning me.

Oh, the interchangeable men on the Google Calendar—Chris, Pete, Rob, Malcolm—like so much bland litter; taking Ubers and Lyfts to restaurants and bars; doing the math to split the bill and match the tip with men who own bicycles more expensive than their furniture, men who are oddly puritanical about hops and vegetables, men who are boastful of their neuroses—the trauma, the therapy, the meta-therapeutic rejection of therapy. One told me in earnest that it was important that I know right away, from the start, that he hated his mother. I just nodded over my Korean short rib, sipped my orange

...more

Men so weak that I have to break up with myself for them. Sperm on crutches, Grandma Rose would’ve said.

I think of my father, and as always, I feel at ease and forever excluded.

sends the tension in the air leaping up quick as an arpeggio.