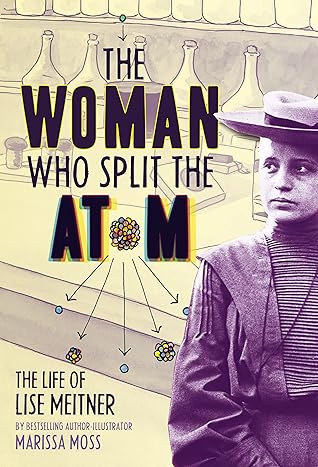

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Marissa Moss

Read between

April 26 - May 10, 2025

Lise Meitner had thought of herself as a completely ordinary little girl, a girl who happened to sleep with a math book under her pillow, as if the equations would slip into her head overnight. Instead of reading novels or poetry like her sisters, she read about the quadratic formula, about figuring out the volume of a cone, about plotting a parabola on a grid. Her brain was full of questions, and she had to know the answers.

She studied the colors in a drop of oil. She noticed the reflections in puddles. She couldn’t stop herself from asking questions about how the world worked. What made the film on the top of the puddle? How did light reflect off it? How could a drop of water be divided? What kept the drop together in the first place? She was “excited that there were such things to find out about in our world,” she wrote later when thinking about her childhood.

Medicine wasn’t Meitner’s passion anyway. Physics was. She wanted to figure out how the world worked, but she didn’t think physics had any practical applications. Medicine seemed the more noble, useful thing to do. So it was a relief when Meitner’s father urged her to follow her real interest. He knew any profession would be difficult for a young woman. To face the many obstacles, you had to care deeply about your subject, be willing to fight constantly for your right to be in that field.

Meitner called Boltzmann’s lectures “the most beautiful and stimulating that I have ever heard . . . He himself was so enthusiastic about everything he taught us that one left every lecture with the feeling that a completely new and wonderful world had been revealed.”

Meitner wanted to follow Boltzmann’s path—she was hungry to discover what she didn’t know, not look for confirmation of how she wanted things to be.

Her mind was quick, her work thorough and careful. She had an uncanny ability to see both the forest and the trees.

Working by herself, Meitner figured out a way to measure the scattering of alpha particles. Her results were important enough to publish in a scientific journal in 1907, when she was just twenty-eight. But even with that boost to her reputation, there was no future for a woman physicist in Vienna.

She was terrified that she simply didn’t belong: “Women’s education was just beginning to develop . . . I was very uneasy in my mind as to whether I would be able to become a scientist.”

Gerta von Ubisch was a physics student who had convinced professors to allow her to audit classes. She couldn’t get a degree, but she could learn. She suggested that Meitner do the same. That little bit of encouragement was all Meitner needed.

She needed a place to do experimental work. So she screwed up her courage to ask Professor Heinrich Rubens, the head of the experimental physics institute, for a lab where she could continue her research. Rubens suggested she could be his unpaid assistant, helping with his experiments.

Meitner wanted to follow her own interests, to run her own experiments. She was trying to figure out how to politely refuse when Rubens mentioned that a young chemist, Dr. Otto Hahn, was interested in collaborating with Meitner. He’d heard of her work in radioactivity and read her one published article.

Meitner jumped at the offer. A lab of her own was all she wanted! She could continue scraping by on her meager allowance and translation work. And even if the “real” labs were off-limits, she was allowed to attend the meetings where the researchers (all men) talked about current projects, presented findings, and shared discoveries. She would be part of a world of scientists. That was all that mattered.

“This group of young physicists made up an unusual circle,” she wrote. “Not only were they brilliant scientists—five of them later received the Nobel Prize—they were also exceptionally nice people to know. Each was ready to help the other, each welcomed the other’s success. You can understand what it meant to me to be received in such a friendly manner into this circle.”

Her friends admired her for her intelligence, her focus, her dedication to physics. There was no other side to her. Without science, she felt she had no identity.

Without her, he was half a scientist, an experimenter without the ability to read the meaning behind the results. He understood the outcomes only in terms of chemistry, able to identify the elements and particles that occurred. He had no idea what was happening within the atomic nucleus, what caused the “new” elements and particles—that was a question of physics. Without Hahn, Meitner wouldn’t have been able to run as many experiments. And his name alongside hers on their published papers gave her instant authority.

Meitner remained an unpaid assistant, still scraping by through translating scientific articles from English to German. Meitner was an expert at living cheaply, eating little, and spending next to nothing on clothes. After all, she had no needs beyond a lab. If she’d been forced to sleep there, she would have.

They published three major papers in 1908, six in 1909, and fourteen in the next three years.

“I love physics with all my heart . . . It is a kind of personal love, as one has for a person to whom one is grateful for many things.”

Meitner wrote, “I almost understood him!” She did grasp some things: “At that time I certainly did not yet realize the full implications of his theory of relativity and the way in which it would contribute to a revolutionary transformation of our concepts of time and space. In the course of this lecture he did, however, take the theory of relativity and . . . showed that to every radiation must be attributed an inert mass. These two facts were so overwhelmingly new and surprising that, to this day, I remember the lecture well.” She would in fact remember the ideas when she needed them most, to

...more

In 1913, Planck brought Einstein to work in Berlin at the KWI. Now Meitner could talk with him at the weekly meetings.

By then, she had an international reputation for her research on radioactivity, but the only teaching job she could get was grading exams and papers for someone else. Planck wanted to offer her a full professorship, but no woman had ever held that title.

She later wrote, “Not only did this give me a chance to work under such a wonderful man and eminent scientist as Planck, it was also the entrance to my scientific career. It was the passport to scientific activity in the eyes of most scientists and a great help to overcoming many current prejudices against academic women.”

As she wrote to Hahn on October 14, 1915: “You can hardly imagine my way of life. That physics exists, that I once worked in physics and one day will again, seems as far away to me now as if had never happened, nor will again.”

By herself, she was doing major work on beta and gamma radiation, proving that after beta decay, secondary radiation—gamma radiation—was released, a chain effect of radiation. Radioactive substances aren’t stable. Instead, they decay until they reach a stable state.

Besides the papers she published with Hahn, she published ten of her own immediately after the war. It was a spurt of productivity, a time when she felt secure in her work—until everything changed.

Meitner continued to build her own equipment from things that could be found in a hardware or housewares store: rubber tubing, beakers, glass piping, wire mesh.

In the 1920s, Meitner was one of the first physicists to use a new piece of equipment, a cloud chamber.

These were the years when scientists were redefining atomic structure, making new, exciting discoveries about what was inside an atom, how it all held together. Meitner was convinced she had her own contribution to make. She wasn’t sure what it would be, but she was determined to see clearly inside the mysterious workings of the nucleus.

In 1920, Meitner published ten articles on subjects like radioactive processes and cosmic rays.

Meitner wrote that “life need not be easy provided only it was not empty. And this wish I have been granted.”

In 1924, Meitner won the Prussian Academy of Sciences’ Silver Liebniz Medal, a first for a woman. The following year, she was awarded the Vienna Academy of Sciences’ Ignaz Lieben Prize. Meitner’s father was proud to see his daughter recognized by their home city, proof that women could be scientists.

Meitner received a new award from an American organization, the Association to Aid Women in Science. It was the first time the award was given, and it was meant to be a “Nobel Prize for Women,” since the Swedish organization was notoriously blind to women’s achievements. Meitner received the award jointly with the French chemist Pauline Ramart-Lucas.

Einstein, who was in California when Hitler came to power, quickly understood the danger. In an interview on March 10, 1933, Einstein said: “As long as the possibility remains open to me, I will live only in a country in which political freedom, tolerance, and equality of all citizens before the law prevail. The freedom of oral and written expression of political conviction constitutes a part of political freedom; respect for the convictions of an individual a part of tolerance. These conditions are not fulfilled at present in Germany. There, those who have especially served the cause of

...more

Terrified of starting over with nothing, of losing her lab, her world of physics, Meitner refused to follow her friends. “It was . . . my life’s work, and it seemed too terribly hard to separate myself from it,” she later wrote a friend. She would be the last Jewish scientist left in Berlin.

Germany was now a fascist dictatorship, intent on ridding itself of all Jews. And still Meitner stayed.

When it was clear that working with a Jew would seriously damage his reputation, Hahn ended their partnership. He still turned to her constantly to interpret results in terms of physics, since he could understand them only in terms of chemistry, but the days of submitting papers together were over. Meitner’s name was stripped from those they’d previously published, part of the Jewish purge from academia.

She was “the Jewess,” whispered about in the hallways as a political liability. Kurt Hess, an avid Nazi who now headed the KWI for Chemistry, argued for expulsion, insisting that “the Jewess endangers the institute.”

Alone, with no students, assistants, or colleagues, just her and physics. In her middle age, she was going back to her early days of scrimping and working, with no salary and no title, back to another kind of basement.

After not working with her for years, Hahn and his new partner, Strassmann, started collaborating with Meitner on this new avenue. They talked about the experiments they would set up, what they were looking for, and how to understand the results, something Hahn couldn’t do without her.

The team published eight articles on transuranics in 1935 and 1936 (with Meitner, like so many years before, listed now as L. Meitner to avoid once again the bias against women scientists). They were an essential part of the conversation among scientists trying to figure out what transuranics were and how they were created on an atomic level.

Not knowing what else to do, Meitner continued to go to the lab despite Hahn’s refusal to work with her anymore. She clung to every scrap of normal life she could find, living off her meager savings.