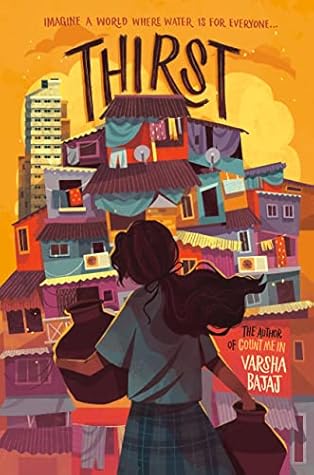

More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Lately the monsoon season comes later and later, which means less and less water.

Although water surrounds my island city, most of the people I know are always struggling to get enough.

We don’t have running water in our house. We just have a tap outside that we share with our neighbors. Ma has to wake up at the crack of dawn to fill our buckets because the authorities only supply water for two hours every morning and for an hour in the evening when the shortages aren’t too bad. The rest of the day, the tap is dr...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

If you invite trouble, it will come. It will stay for chai and for dinner.

What? Computer class! My eyes are wide. The small room suddenly feels spacious. It’s as if the word computer, spoken aloud, has magically created windows in the walls where none existed.

“Were the people who lived on the islands part of the dowry?” she asks. “Were we like cattle, of no importance back then?” “We aren’t exactly important now either,” says Sanjay. “Which is why we don’t get water. And get questioned before we enter fancy shops. As if we might steal.” “You are bringing up an important point,” Shanti says, using her best teacher voice.

Then the roof of the car starts to open with a whooshing sound, and we can see the sky. Uncle sees our amazed faces. “Go on,” he says. “Stand up, push your head out through the roof, and look at the world.”

“Did he?” she whispers. I weigh my choices. If Sanjay is my brother, Faiza is my sister. It doesn’t matter that we have different mothers or believe in different gods. I cannot get through this time alone. I need her. Plus I know she can keep a secret. So I tell her the truth.

Is this growing up? Learning how dangerous the whole world can be? Learning that not everyone follows the rules. That some people don’t care if they hurt others. That they only care about themselves and making a profit.

The air smells different, and we grow vegetables that get sold in the bazaar,” Sanjay told us. “The air? How so?” I asked. “It smells fresh—like the earth after rain. It smells of the apples growing on the tree.”

“Shanti, I’ve been thinking a lot about the story you told us about how the land here was reclaimed from the sea.” “What were you thinking?” “You said the land was once marsh and that the ground wasn’t as strong as we thought it was.” She raises her brows. “My family wasn’t as strong as I thought it was either. My mother’s sick and had to go stay with her family in their village. Sanjay left too . . .” I can’t trust myself to say anything more. But even without more details, Shanti understands what I need to hear. “Minni, I did say that the ground was marshy, but don’t forget that it has held

...more

“You’re not alone. You’re very brave.”

“Remember—trouble can take a minute to get into and a lifetime to get out of.”

can’t help staring at her wall of filled bookshelves. Has she read all these books? Then I see a desk in the corner of the room, and it holds Pinky’s very own computer. I’d like to reach out and touch everything. For a moment, a pang of jealousy stabs me. Does Pinky realize how lucky she is?

Anita Ma’am leads me into a bathroom that’s attached to Pinky’s bedroom, and I stare at it in wonder. In my neighborhood, thirty families share a bathroom at the end of our lane that has seven stalls. And for a bath or shower, most of us use a bucket of water. Pinky has her very own tub. She can close her own door and bathe in it in privacy. Imagine.

“You need to wet it first,” says Pinky. “I’ve watched Rohini do it.” Why does Pinky call Ma by her name as if she is her equal? I’d never call someone my mother’s age by her name. I always call them Aunty or Ma’am. I look around the bathroom. There is no bucket filled with water. Then Pinky turns on the tap, and to my astonishment, water gushes out. It flows freely in the middle of the day. Like it’s magic. The rich really do live in a different world!

I count my steps. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten. Pinky’s bathroom is as big as our house.

palak paneer

I look down at myself. My skirt’s wrinkled. My blouse has escaped the waistband. And my ponytail’s coming loose. I tuck my blouse in and try to smooth my skirt. Seeing Faiza’s hair in neat braids and her ironed uniform makes me miss my ma even more. I guess I need to do a better job at growing up.

Minni, Ammi has packed enough lunch for both of us. She made your favorite, jeera aloo. I read it a few times. Her mother remembered that I love jeera aloo and that Ma wasn’t there to pack me lunch, so she did. Naan Aunty brought me dinner. Faiza waited for me, and Shiva the guard let us in. Miss Shah didn’t question us for being late. At lunch I feel the caring in every bite. Shanti told me I wasn’t alone, and now I see what she meant. This growing-up thing is hard—and the carefree days of my childhood may never return. But I have so many people here to help. That night I write in my journal:

...more

“She’s like a really cool big sister and talks to us like we’re her equals.” “That’s nice,” she says. “But between your job and Pinky and her horrible grandmother, and now Priya Didi, you never ask me how I am.”

The computer class opened a door into a fairy-tale world, and I forgot my reality, which is far from magical.

If I had met Pinky at school, we’d probably be friends. Except in our world, Pinky and I could never be in the same school.

our parts of the city—the parts that people call the slums—get only 5 percent of the city’s water supply, but we have almost 40 percent of Mumbai’s population.

About a dozen women are already in front of me. One of them turns to me. “What’re you doing at home, Minni?” Before I can answer, another aunty says, “Rohini went to her village. She’s not well. Minni, have you had to stop going to school?” It’s funny how they ask me questions but don’t wait for me to reply. “Nothing wrong with that. I stopped in seventh grade too.” “At sixteen, you can be married, with that beautiful skin of yours.” “Men don’t want to marry girls who are too educated, anyway.” “That is the truth.” I want to flee, but I need water. “Rohini says you never stop talking. Where’s

...more

“Look at Latika—she sells magazines by the traffic lights, helps her family, makes a living. That’s a respectful daughter.” They’re like vultures, and I’m the carcass. Latika looks at my crumpled face and whispers, “They don’t realize what they’re saying. Try to ignore them.”

“Aren’t you saying I have a lot on my plate? Just not food,” I joke, and it feels good to make Sanjay laugh.

Technology can give us power. I feel like the goddess Shakti, who fights evil and sometimes rides a tiger, instead of powerless me.

When a fear is too terrifying, I realize, we are scared to give it words, as if that will make it all too real. But the anxiety doesn’t go away. It’s like a weed that continues to grow, sprout, and choke the plant.

We watch as a man dressed in long khaki pants and a matching shirt gets out of one of the police cars and enters the gate. We recognize him. We’ve seen him on TV. He’s the new police chief that the policemen in my father’s shop were talking about. The one who is shaking things up and has a reputation for being able to stand up to the corrupt gangs.

The police chief walks out, and behind him is Pinky’s father. In handcuffs. His eyes are focused on the ground. Two other policemen are holding his arms. The bystanders gasp, and Ma almost faints.

What I do know is that I worked to right a wrong. And that the man who could have crushed us like ants no longer has that power.

“One day is not today,” Sanjay says. “Here I’ll be a real cook. In Mumbai, I cut vegetables.” “Right.” My voice shakes as I admit this. “You’re right.” “This is what I want to do, Minni. You know, you and me, we’re both thirsty for more. You for an education, me for an opportunity.” Sanjay is right. We are both thirsty. And it’s our time to do the things we want.

“But, Minni,” Gita says, “not everyone has a phone.” “Ah, good point,” I admit. “Of course they don’t.” “And how will you deal with the people who just line up and don’t use the app?” Amina asks. More good points. I realize I was so excited by the idea that I didn’t think it through well enough. Seeing my disappointed face, Priya Didi says, “Minni, all good ideas come with problems. That’s part of the challenge. Your idea is solid. But you have to keep working on all the angles. These are glitches that all our apps will face.”

Lately I’ve seen way too much of the bad side of human nature. And since I can’t “see no evil,” I’m happy I can also see the good.

Full of the confidence that everyone has in me and my future. Ready to take on the world and keep dreaming. Like so many who’ve come before me, I will stay strong, even as the waves crash around me.

Thirst was written in 2020, a year of collective trauma, when COVID-19 closed borders, kept me from visiting my family in Mumbai, and bound me to my desk in Houston.