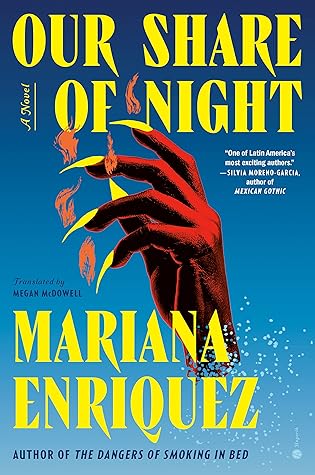

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

It was the illness, he’d explained to her later. Each thing he did was a negotiation, a calculation. As if he were tasked with carrying and caring for a delicate crystal treasure that he could never set aside, not even in a safe place, and that had to be moved gingerly so as not to damage or break it. He had to think out every movement in advance, always tiptoeing, always wondering if this jolt would bring the disaster, the final break.

But my love, stupid girl, we won’t be you and I, there is nothing in that place but shadow and hunger and bones, that world is dead.

he stayed until the darkness withdrew, and then he touched the boy’s motionless heart again and whispered, Come on, you’re here for a reason, if you are the voice of the gods then beat, and the heart started beating between his fingers as though it had never stopped.

I must not think of my glory. Let it be secret if it must. I will stop pleading for compassion. There are no words from this world for the entrance into the Darkness, no words for the last bite.

I hope he dies, he thought. I hope Dad dies once and for all and puts an end to all this and I can live with my uncle or with Vicky or alone in the house and I don’t ever have to think again about locked rooms, voices in my head, dreams of hallways and dead people, ghost families, boxes full of eyelids, blood on the floor, where he goes when he leaves, where he’s coming from when he returns, I wish I could stop loving him, forget him, I wish he’d die.

He wanted to believe the story of the crash and the amnesia, but, with a certainty that he recognized and wasn’t about to ignore, he knew that his father had hurt him. In a deep and unimaginable way, of which the bruises and cuts and the bump on his head were merely slight, superficial vestiges.

You have something of mine, I passed on something of me to you, and hopefully it isn’t cursed, I don’t know if I can leave you something that isn’t dirty, that isn’t dark, our share of night.

he also remembered his father’s words, Nothing can hurt you now, how long was now, how long did the present last?

“You are what I love most in life, Gaspar.”

That’s what it meant to be an orphan: to have boxes of ashes and not know what to do with them.

It’s the house my mother hates, because she hates everything beautiful and wants to destroy it; that is her true faith and her nature.

That is also what it is to be rich: that contempt for beauty and the refusal to offer even the dignity of a name.

All fortunes are built on the suffering of others, and ours, though it has unique and astonishing characteristics, is no exception.

That was when I learned that it’s customary in the Order to let members leave without trying to retain them. My mother says they must be allowed to go because they always come back, they come crying back, all beaten down, because the Darkness is a god with claws that sniffs you out, the Darkness catches up with you, the Darkness will let you play, the way a cat lets go of its prey just to see how far it can get.

how can we go on after this, how do you all do it, the world is stupid, the people who know nothing are contemptible. And he gave an answer that was so true I sometimes repeat it out loud. The thing is, nothing happens after this, dear. The next day, we get hungry and we eat, we want to feel the sun and we go swimming, we have to shave, we need to meet with the accountants and visit the fields because we want to keep having money. What happens is real, but so is life.

He was only fragile because he was sick. Fragile like relics, ancient ruins, sacred bones that had to be cared for and protected because they were incalculably valuable, because their destruction would be irreparable.

Love is impure, said her aunt, but Florence believed that love was inevitable and could also be set aside. That was the sign of true strength. To put love aside.

But I can only help him in minor things, with my stupid protections. He hates when I call them stupid because he loves and respects me, but they are. All the little spells in this world are dust, they’re nothing, they’re specks of dirt in the blood of someone like him.

Did your father sell you, too, like mine did? We are servants to those people, we are the flesh that they torture. We’re the rickshaw drivers transporting rich little girls in India. I’m the lumberjack who fucks the plantation owner’s daughter. You’re going to have to disobey them if you want to follow me.

The river sounded like it was running faster. It grows because it eats. Juan is its mouth, and the gods are always hungry.

“Go on, my love. Leave me. I can’t go, but you can, you can escape me, and them. There is nothing, Rosario, it’s just fields of death and madness, there’s nothing, and I am the doorway to that nothing and I’m not going to be able to close it. There’s nothing to find, nothing to understand.”

I took Juan by the neck without any delicacy—it wasn’t needed—and I could feel his pulse in the palm of my hands. Do not die today, I ordered him, and I looked into his eyes that were a little green and a little yellow. Don’t die, and if you can, take my mother.

I knew him well enough to recognize his way of showing affection—behaving like the world was a porcupine and he couldn’t find anywhere to sit.

The man says nothing. The victims’ fathers tend to be silent companions. Many have died during these years spent in the background, accompanying their wives. They’re killed by impotence and love; they’re unprepared. Women know how to manage these emotions better.

“It’s not gay to read poetry.”

It’s like we’re all going up a flight of stairs together and at a certain point I say “this is as far as I go.” And on that step, higher up, they’re all happy and I watch them from below.

He could dance when he was alone, he could get emotional in his room with a book, but when the party started he disconnected, the others turned into a movie that he could watch but not participate in.

They sought me out, here I am. I don’t know how to let go of the dead.