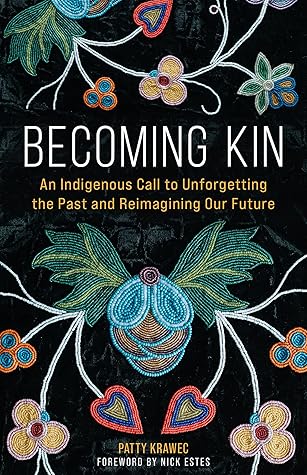

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Patty Krawec

Read between

July 24 - August 30, 2025

“Grief is the persistence of love,” Krawec writes. Indeed. Grief and love are not bound by time and space.

Grief is also about remembering, or unforgetting, the future and a history that could have been. We were first colonized when they took away our collective sense of a future. The evidence of that crime lies in church and government lands interred with the remains of Native children, the evidence of a future they tried to snuff out.

As Lakota people, we recognize becoming human is hard. It is marked by terrible suffering and profound beauty, especially in an age of cacophony and chaos. But at the center of making relations is love, ceremony, song, laughter, and crying.

NII’KINAAGANAA We are related. Nii’kinaaganaa. My friend Josh Manitowabi breaks down this Anishinaabe word like this. Nii: “I am” or “my.” Kinaa: “all of them.” Ganaa: “relatives, my relatives.” The phrase could mean any of these things: I am my relatives, all of them. I am related to everything. All my relations.

From our earliest creation stories, the Anishinaabeg (plural of Anishinaabe) understood themselves to be related not only to each other but to all of creation. Our language does not divide into male and female the way European languages do. It divides into animate and inanimate. The world is alive with beings that are other than human, and we are all related, with responsibilities to each other.

Perhaps being called a “settler” feels aggressive—a suggestion that you do not belong, despite generations of being here. You think of yourself, or perhaps your ancestors, as immigrants. Not settlers. Settlers are not immigrants. Immigrants come to a place and become part of the existing political system.

“History is the story we tell ourselves about how the past explains our present, and the ways we tell it are shaped by contemporary needs,” writes poet and activist Aurora Levins Morales, a Jewish Puerto-Rican woman. “All historians have points of view. All of us use some process of selection by which we choose which stories we consider important and interesting . . . storytelling is not neutral.”

As a foreign religion and perpetrator of colonization, Christianity is part of the other boat. He sees Christianity as it exists broadly across the Western world—a faith disconnected from land and strangers, ideas imposed by white Europeans who arrived as guests but almost immediately began to act as autocratic hosts.

All of our creation stories tell of a new people for a new world. But what that new world will look like will depend on what our roots sink into, wrap around, and bring to the surface.

When we return to ourselves, we undo the colonialism that has gotten inside our heads. We can only do this if we are willing to understand our history differently, if we take our stories out of isolation and put them together. We need to revisit the stories we tell ourselves—about how we got here—and see something different, see something that allows us to become relatives again. To put back together what modern ideas about race have torn apart. “Ultimately what we inherit are relationships and our beliefs about them,” writes Aurora Levins Morales. “We can’t alter the actions of our ancestors,

...more

In her book Knowing Otherwise, Alexis Shotwell describes various forms of knowledge. She notes that as individuals and as communities, we hold knowledge in ways that we can articulate or explain to others and also in ways that are less tangible—knowledge that we can’t articulate in the same way.

And I think often about something that Dr. Tiya Miles said about history in a discussion that I once organized. Miles, an African American historian, said there are gaps in our stories: gaps in Black studies where Native people should be and gaps in Native studies where Black people should be. We are not discrete categories of people upon which colonialism acts in different ways; we are a Venn diagram with areas of huge overlap. The gaps Miles refers to are the work of settler colonialism pulling us apart.

This book, in helping us reclaim our interconnected histories, will take us to a place of becoming good relatives. We are all related, and we will see in the next chapter that all creation stories tell us this. But what does it mean to be good relatives—to not only recognize our kinship but to be good kin? Because, for Indigenous peoples, kinship is not simply a matter of being like a brother or sister to somebody. It carries specific responsibilities depending on the kind of relationship we agree upon. An aunt has different responsibilities than a brother. If we are going to be kin, then we

...more

Rather than cutting off our roots because we are ashamed or afraid of what we will find, we can learn our history. We can reimagine the relationships we have inherited, and we can take up our responsibilities to each other.

For the Anishinaabe, fire is an environmental technology used to shape the landscape, to cleanse and make space for new growth. In that context, these fires are more than gathering places. They are wildfires—episodes of social and spiritual cleansing, of making room for new beginnings.

Aambe As we prepare to reconsider the history that we have learned, look for Black and Indigenous people. Look for us in your life, on your bookshelf, in the music you listen to and the movies or television you watch. Look for us on your social media feed. Look for us in the collective nostalgia of your country. Don’t try to read too much into our presence or absence. Just notice. Where are we?

This is a central theme in literature and movies; from Wagon Train to Star Trek, Americans admire this desire to boldly go and then bravely defend themselves from those who resent discovery. Discovery, after all, has never been good for those it has uncovered. It inevitably leads to exploitation and death.

Christians are unmoored, landless people. Maybe that disconnection from land is what has led to other disconnections.

I remember learning in church that this world was not our home, that we were strangers in a strange land and that our hope was in heaven. That changes how you look at things. Instead of listening to what the land might have to say for itself, you listen only for what God might be saying through it, reducing it to an empty vessel. It diminishes our investment in the world around us and disconnects us from everything, including people, because we don’t listen to them either.

Creation stories speak of emergence. The Genesis creation story places the emergence of people in Mesopotamia, the region of the Tigris and Euphrates, where grain and large cities like Uruk developed. The Anishinaabe creation story places us in the woodlands north of what is now called Lake Superior. The Hopi, in a land of deep canyons, emerged from a hole in the ground. The Inuit emerged from holes in the ice. Our creation stories situate us in a particular place, with particular relationships.

Creation stories, whether Christian or Hebrew, Anishinaabe or Hopi, aren’t meant to be histories—not in the sense that the Western world has invented the idea of history as an unbiased set of facts. They are meant to explain who we are and create a communal sense of self.

Across the Americas are many nations whose creation stories and belief systems are sometimes very different. Just as the garden of Eden is located geographically by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, our creation stories are also located geographically in places all over the continents. We were used to multiple creation stories, peoples whose circling created their own centers. We understood how to live together with these multiple eddies, circular currents that draw up nutrients from the colder, deeper waters.

When these European Christians arrived in worlds they called new, they were again confronted with new stories, with unfamiliar people, and they had to figure out where we fit in. Who were we? If the Bible talked about everything, as they thought that it did, then surely it must mention us somewhere.

Over and over, these settlers have written themselves on top of our stories, taking small parts of our stories and fitting them into the biblical narrative. Even when they did listen to our stories, it was only to hear fragments of their own story, not to understand ours. They had good news for us, after all; why would they think we might have good news for them? Just as humanity’s ancient mother was transformed into Mitochondrial Eve, we, too, have been recast into the Bible’s story.

Indigenous peoples have creation stories that root us in our own places, that tell us who we are and what our relationship is with our Creator and the world around us. Forcing us into a different creation story begins our disconnection from the land. We have always been here: this is how we understand ourselves. And it is true, even if we did migrate from somewhere else more than one hundred thousand years ago. Our own creation stories are filled with migration and travel. But this land is where we emerged as peoples; this is where we developed our political systems and cosmologies. This is

...more

Multiple creation stories, emerging from multiple gardens, describe the relationships of multiple peoples. There is not a single story to which we must all be reconciled. Not a single story with a single message. Not a single narrative that provides its bearer with authority and power to control the lives of others.

Having a single creation story not only made ours wrong; it created a power differential that placed European Christians, who knew the truth, above the Indigenous peoples, who lived in darkness. Europe, dominated as it was by Christians, had a single creation story and had previously dealt with difference by eliminating or absorbing it. But the Americas had many; we had learned to live with multiplicity.

What if the early European colonists, instead of thinking of us as having wandered from the truth, had considered our own emergence as people in relationship with this place? What if they had seen God’s presence in this place instead of emptiness and absence? What if the settlers, instead of reenacting the conquest of Canaan, had pursued relationship? What if they had sought kinship?

Land acknowledgments are statements recognizing the Indigenous people who lived in the area, as well as those who still live here and who contribute to the existence of this place. At its worst, the impulse to use land acknowledgments is akin to thinking that admitting that you stole a TV set means it’s okay to keep it.

Land acknowledgments are a moment to pause and reflect on the relationship that exists between the current residents and those who were displaced. What does it mean to live on stolen land? You may not be guilty of the act of dispossession, but it is a relationship that you have inherited. Who lived in your area before colonization? Who still lives there?

From the very beginning, the newcomers worked to destroy Indigenous people. Their aim included destroying our beliefs about ourselves and our relationship with the seen and unseen world and replacing them with European Christian beliefs. We were made to fit into their history, their cosmology, and their economic system.

Developers still say that it “isn’t being used” when they want to develop an area of land. But that only means that people aren’t using it in a particular way. Plants and animals are using it. People are using it. It is never a matter of whether the land is being used. It is how and who that matter—that prioritize one set of uses over all others and give one group the right to push aside another.

They recognized the rights of not only the humans involved in the treaty-making process but also other relatives. Remember that for Indigenous peoples in the Americas, the entire world is alive with people—and not just those of the human variety.

Our various traditions speak of treaties made with plant and animal nations, who provided sustenance for us in exchange for care and respect. This hearkens back to our creation story and the belief that we had all collectively promised to take care of each other.

The Bible offers many mechanisms to mitigate the accumulation of wealth. It offers striking examples of generosity and commitment to relationships such as those found in the early church, and it also condemns those who choose wealth and isolate themselves in the face of others’ need.

Many Indigenous nations had mechanisms that prevented the accumulation of wealth, and these mechanisms were forbidden by the US and Canadian governments. From the giveway in the East to the potlatch on the West Coast, Indigenous peoples measured wealth by what was given away. You gave away everything to celebrate a major event, knowing that in the midst of this, your needs would still be met. Just as many did in the book of Acts, Indigenous people would sometimes give everything because they were confident that their community would meet their needs.

For four hundred years, settlers swarmed over the continent, following waterways and trails they carved into mountains. They burned across the prairie like a wildfire consuming the deep-rooted grasses and leaving thirsty crops like wheat and corn in their wake. Creative and innovative, they used whatever strategies they could to push us aside. The missionaries often came first, then traders and settlers, all with the protection of the military and laws that justified theft and displacement. By the late nineteenth century, the West was won. Manifest Destiny rested on Enlightenment beliefs about

...more

The Trail of Tears was the most well-known removal of the Cherokee from Georgia to Indian Territory. Yet it is only one of several removals that took place in the 1830s, an ethnic cleansing of the lands east of the Mississippi. Clearing these states not only freed thousands of acres for plantations and led directly to the rise of King Cotton but removed Indigenous tribes who often acted as allies for escaped slaves. More than one hundred thousand Indigenous peoples were removed from the eastern seaboard, replaced by enslaved Africans whose labor enriched those at the top of the social

...more

The term environmental racism was coined in the 1970s to capture this pattern of locating industrial processing, waste storage, incinerators, and bridges near primarily Black and Indigenous neighborhoods and lands.

Natives, Africans, Europeans, and more all have migration stories. We all moved. We moved across oceans and land. But there is a profound difference between moving and being moved. Between being welcomed and being used.

When Senator Henry Dawes visited the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma decades after their removal, he found them to be thriving. This surprised him. They had a school, hospital, and bicameral system of governance. Nobody did without. According to Dawes, this was socialism. There was, he said, “no incentive to make your home better than that of your neighbor. There is no selfishness, which is at the bottom of civilization.” This propensity for collective ownership confounded settlers, who understood the buying and selling of land as the basis of wealth and civilization. The Dawes Act was their

...more

Genocide is a legal term that emerged in the aftermath of World War II. The UN Genocide Convention—adopted by the member countries in 1948 but not ratified by the United States until 1988—defines the crime of genocide as “any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group as such: (a)Killing members of the group; (b)Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c)Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

...more

These are the family values that America is built on. But whose family is valued, and whose family is removed? Removals of all kinds mean that the homes of Black and Indigenous people, migrants, and those whose religious beliefs placed them outside of Christian norms are kept unstable and precarious.

I worked for a child welfare organization in Canada for sixteen years. I had not gone into social work with the intention of doing child welfare, but during a placement with a community organization, I discovered that I liked working with families. Working for an organization whose mandate was the protection of children seemed like a good place to do that. Like many of the people who had worked in boarding schools, I believed in my good intentions. I didn’t think about the larger structure and the patterns that were at work.

There is no question: children deserve to be safe. But in all of my conversations at work about the risks that children faced inside their homes, we never talked about the risks that these children would face when we removed them. Most of the families that come into contact with child welfare services don’t ultimately have their children removed from their care. That fear is ever present for parents, however, because its unspoken threat is behind every question, every suggestion or command. Parents know what the child welfare worker has the capacity to do.

Children deserve to be safe. But the language of safety has never meant true safety for Indigenous children. Just as with Indian boarding schools, the vocabulary of “safe” and “educated” and “civilized” has been used to justify war against our communities and to separate us from our families. Policies that define what “acceptable” homes and families look like disrupt our own family and communal practices. After governments and people with good intentions destabilize our communities, the language of safety is used to destabilize them further. If we wanted families to do well, we would put

...more

We don’t know why Metoaka made the choices that she did. But we know that it began with an abduction. We also know that women who marry into patriarchal societies tend to become what David W. Anthony calls “hyper-correct imitators.” They become more proper than the ones who were born within the society, in order to keep themselves safe, to feel less vulnerable. They do what they can to feel safe. And they still aren’t safe.

Sexual assault is often framed in terms of what the victim was wearing or doing or drinking. But sexual assault is the imposition of power; it is about who the victim is. And that is something that Black and Native women and girls and queer or two-spirit people can’t do anything about. White women are taught that they can keep themselves safe as long as they conform to certain ideas about how proper white women behave. It isn’t true, but it provides them with the illusion of control; it is a way of showing the world that they are respectable and worthy of care, not like “those other women” who

...more

Grief is the forgetting of names. It does not know which place the ancestors’ feet last touched before leaving home forever. It looks back over shoulders and sees only darkness. Stolen lives means stolen history means no thread to pick up and follow home.

I want us to consider our relationship with land—to think about it beyond squabbling over ownership and rights and to think about responsibilities and reciprocal relationship. To think of ourselves as a part of creation rather than apart from it. What if the land is a being in its own right? That concept is not as foreign as you might think. And what if the land and all that grows from it and on it and in it are sentient beings in their own right? Then we need to make material changes that restore the land to our original agreements. We need to remember that the land belongs to itself, and

...more