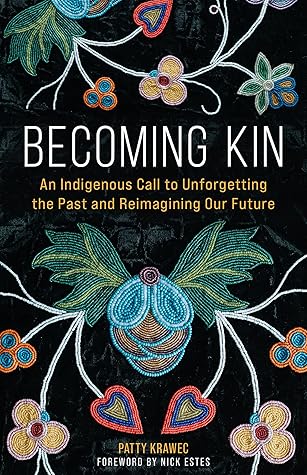

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Patty Krawec

Read between

March 16 - March 22, 2023

the church is a pale shadow of what it could have been, should have been. The dominant church is running wild and unshod over this beautiful earth, with no regard for anyone else. A people who, despite grasping for power, have become ruins and hollow bones. Western Christians have, as they say, lost the plot. Throughout this book, we will trace that loss, that forgetting, and in reclaiming history, we will unforget the things we used to know.

Settlers are not immigrants. Immigrants come to a place and become part of the existing political system. When the colonists arrived in what would become the Americas, there were many political systems already in existence. Ours. And although the Haudenosaunee system likely inspired or shaped the US system of governance, there has never been a time when those who came to these shores collectively became part of any of our political systems. (Exceptions may include those who became the Métis, the Lumbee, and the Seminole.) Settler is a way of being here. Through this book, I hope to offer you

...more

Like many Native people born between 1960 and 1980, I grew up in a blizzard of whiteness, surrounded and loved by my maternal German Ukrainian family but without any connection to my paternal Ojibwe family. I had photographs of my father and my Ojibwe kin but no relationship and no idea how to even begin. It wasn’t until I was in my midtwenties that I found my father and began taking tentative steps toward the larger Indigenous community, which turned out to have been there all along. After decades in colonial darkness, I am ready to step into the light.

“History is the story we tell ourselves about how the past explains our present, and the ways we tell it are shaped by contemporary needs,” writes poet and activist Aurora Levins Morales, a Jewish Puerto-Rican woman. “All historians have points of view. All of us use some process of selection by which we choose which stories we consider important and interesting . . . storytelling is not neutral.”

The principle of noninterference lives at the root of many Indigenous philosophies and is exemplified in treaties like the Two Row: we would live according to our ways, and the newcomers would live according to theirs. Although colonization is clearly a violation of this treaty, the Haudenosaunee people I know remain committed to it and continue to try to live within these principles.

But as I understand them, the two rows—those of the Indigenous peoples and the settlers—aren’t meant to completely isolate us from each other; they are meant to guide our relationship so that we can live together. And what I know of the worldview of the Anishinaabe is not completely inconsistent with what Christianity could be. I see other possibilities: the original instructions of connection, relationship with land and people. The original instructions as recorded in the Bible are frequently disregarded or redefined in service to settler-colonial ideas about how a society ought to be

...more

Settlers and newcomers, Black and Indigenous: the history we learn in elementary school is rooted in explorers and settlers. We learn about brave colonists fighting for freedom. We learn about Native people who, despite early Thanksgiving friendship, become dangerous and then mysteriously vanish. The history of slavery is placed comfortably in the past. The American story is one of a war fought to end slavery. The Canadian story about slavery is being the final stop on the Underground Railroad, the place of freedom. We all, settler and newcomer, Black and Indigenous, learn about how these

...more

Colonization has gotten inside our heads. It is more than driving cars and talking on iPhones, more than the food we eat or where we shop. It is how we think. We often put colonialism in the past, dressing it up in sixteenth-century costumes. But as Patrick Wolfe has said, colonialism is a process and not an event. Settler colonialism came to stay in the Americas in the sixteenth century, but it neither started there, nor has it stopped. It cut its teeth on the Crusades, where the rape and violence enacted on Jews and Muslims were the price of Christian freedom. A violence that persists and

...more

To put back together what modern ideas about race have torn apart. “Ultimately what we inherit are relationships and our beliefs about them,” writes Aurora Levins Morales. “We can’t alter the actions of our ancestors, but we can decide what to do with the social relations they left us.” In order to understand these relationships, we need to listen to the histories that we were not told so that we can begin to remember the things buried beneath the histories we were.

The divisions between us are only possible because we have forgotten our history, forgotten our creation stories. Forgotten how to articulate the knowledge that is held in unspoken ways. Unforgetting is the process of reclaiming that knowledge—of moving these truths that our society holds silently out to where we can articulate them and examine them. Then we can see if they really are a center worth revolving around, worth the emotional response they engender.

what does it mean to be good relatives—to not only recognize our kinship but to be good kin? Because, for Indigenous peoples, kinship is not simply a matter of being like a brother or sister to somebody. It carries specific responsibilities depending on the kind of relationship we agree upon. An aunt has different responsibilities than a brother. If we are going to be kin, then we must accept that these relationships come with responsibility. In our settler-colonial context, relationships between us are built on a paternalistic foundation: charity and good works, helping the less fortunate.

...more

How do we restore relationships and balance to what has been made so precarious? The promises of the white Christian West have failed to materialize, and we are, socially and literally, on a precipice. How do we go from living in isolated silos to becoming good relatives? How does the church stop running wild and unshod and put down roots that reach deeply into the ground? We can draw on everything that our roots have pushed through and around and pulled forward. Rather than cutting off our roots because we are ashamed or afraid of what we will find, we can learn our history. We can reimagine

...more

History is not a clean story of progress, no straight trajectory from barbarism to civilization, ever marching forward. We live in a constant state of tension between equity and inequity, with people or societies holding more or less power in different places and times. We need to go back to the beginning—or, rather, to a story of new beginnings—in order to start again.

I remember learning in church that this world was not our home, that we were strangers in a strange land and that our hope was in heaven. That changes how you look at things. Instead of listening to what the land might have to say for itself, you listen only for what God might be saying through it, reducing it to an empty vessel. It diminishes our investment in the world around us and disconnects us from everything, including people, because we don’t listen to them either. Relationships become a means to an end, a way to evangelize people so they, too, can become unmoored and disconnected from

...more

The modern church and the modern US state imagine a straight line connecting them through the Reformation to Rome and, for some, all the way to the garden of Eden. Everyone else needs to be corrected or pruned off.

We are maize. The original peoples of the Americas emerged as nations after centuries of merging and splitting, and although we are all related, we retain characteristics related to the land where we emerged. We continue to develop, and as a result of colonization, many of us live in new urban centers, forming communities without our communities. We are changing, and something new is emerging.

What if the early European colonists, instead of thinking of us as having wandered from the truth, had considered our own emergence as people in relationship with this place? What if they had seen God’s presence in this place instead of emptiness and absence? What if the settlers, instead of reenacting the conquest of Canaan, had pursued relationship? What if they had sought kinship?

Land acknowledgments are a moment to pause and reflect on the relationship that exists between the current residents and those who were displaced. What does it mean to live on stolen land? You may not be guilty of the act of dispossession, but it is a relationship that you have inherited. Who lived in your area before colonization? Who still lives there?

Developers still say that it “isn’t being used” when they want to develop an area of land. But that only means that people aren’t using it in a particular way. Plants and animals are using it. People are using it. It is never a matter of whether the land is being used. It is how and who that matter—that prioritize one set of uses over all others and give one group the right to push aside another.

It was into that web of relationships that the Haudenosaunee welcomed the newcomers with the Two Row Wampum. But that was not the kind of relationship that the newcomers had in mind. The settlers turned everything into parcels and products that could be bought and sold and speculated in. And the Doctrine of Discovery—a bundle of laws and proclamations developed by the church about who had the right to land—meant that they didn’t even have to buy it. They could just take it.

words like wild and savage that questioned our humanity and value—was first used against the Irish when England colonized that island. The English, whose history is rooted in their colonization by ancient Rome, saw themselves as Rome’s heirs and better for having been “civilized” by Rome. In their writing and retelling of history, Rome had brought Christianity to the British Isles and, along with it, civilization, and they would do the same for the rest of the world. Whether the rest of the world liked it or not.

The Dish with One Spoon wampum treaty—or One Dish One Spoon, as it is also known—is an agreement between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Anishinaabeg. The bowl represents the land around the St. Lawrence Seaway up into the Ottawa Valley and around both sides of the Great Lakes, reaching into the lands around them. The area described within this treaty is rich in resources. It contains the largest freshwater system on the continent and millions of acres of arable land. Between Lakes Erie and Ontario are micro-climates that permit the growing of grapes and soft fruits well above their

...more

It is the authority by which the European empires claimed ownership of land that was already occupied by sovereign people, something the United States and Canada recognized in their decisions to make treaties with us. Patrick Wolfe describes this in his book Traces of History, in which he discusses the treaty process by which the US and Canadian governments dispossessed the Indigenous peoples.

Both the Dish with One Spoon and Two Row treaties provided a way for distinct peoples to live together without conflict. They recognized the rights of not only the humans involved in the treaty-making process but also other relatives. Remember that for Indigenous peoples in the Americas, the entire world is alive with people—and not just those of the human variety. Our various traditions speak of treaties made with plant and animal nations, who provided sustenance for us in exchange for care and respect. This hearkens back to our creation story and the belief that we had all collectively

...more

In Leviticus 25, the Hebrew people are told to count off seven years of Sabbaths and that the fiftieth year would be a year of jubilee throughout the land. Rather like the European powers divided the Americas and Africa among them, with no regard for the Indigenous nations already living there, the land of Israel was divided among the tribes with family allotments. They had the ability to buy and sell and to lease and mortgage. But in the fiftieth year, everything reverted back to where it had been. Enslaved people were freed, debts were forgiven, land was restored, and the ledger was wiped

...more

Many Indigenous nations had mechanisms that prevented the accumulation of wealth, and these mechanisms were forbidden by the US and Canadian governments. From the giveway in the East to the potlatch on the West Coast, Indigenous peoples measured wealth by what was given away. You gave away everything to celebrate a major event, knowing that in the midst of this, your needs would still be met. Just as many did in the book of Acts, Indigenous people would sometimes give everything because they were confident that their community would meet their needs.

Wealth is inevitably held in the hands of the few, brought to the insatiably hungry big brother by those he has enslaved. The question remains: When will the little brother finally stand up and say “enough”?

The cities of Mississauga and Toronto are nearby. I live in Canada, and our capital city is Ottawa. We have provinces named Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, just as the United States has states named Alabama, Idaho, Hawaii, Arizona, Connecticut, and more. I have cruised on the Chicago River and embarrassed myself singing about the Tallahatchie at karaoke. Washington crossed the Delaware, and I’ve driven over the Mississippi. They are part of our everyday vocabulary, yet they are ambient sounds that fill in the silence and that no one really notices.

The story of colonization is one of displacement, of disruption, of ghosts left behind and of those who make flutes of their bones. The early colonists made deals for land, paying tribute and living in often uneasy peace with their Indigenous neighbors, but this period did not last. As we saw in the last chapter, European hunger for land was insatiable. They just kept coming.

For four hundred years, settlers swarmed over the continent, following waterways and trails they carved into mountains. They burned across the prairie like a wildfire consuming the deep-rooted grasses and leaving thirsty crops like wheat and corn in their wake. Creative and innovative, they used whatever strategies they could to push us aside. The missionaries often came first, then traders and settlers, all with the protection of the military and laws that justified theft and displacement. By the late nineteenth century, the West was won. Manifest Destiny rested on Enlightenment beliefs about

...more

The Doctrine of Discovery entitled Christian explorers not only to land but to people, as long as the people they found weren’t already Christians. These twin entitlements—to land and to bodies—formed the basis for the nations of the Western Hemisphere. These nations are built on stolen land and displaced people. Background noise.

The land to which the eastern tribes were removed—the land that the US government designated as “Indian Country”—was not empty. The southern plains were home to the Caddo Confederacy and the Kichai people long before the nineteenth century. The Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche people had moved in, pushed out of their lands by the Spanish as they moved their empire north.

The story of America as a nation of proud immigrants is a myth, one that Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz unpacks in her book Not “A Nation of Immigrants.” Put simply, immigrants come to a place and join with the existing political order. Settlers come to a place and impose a political order. Those who came here by force—such as African people who were enslaved—or those who come through desperation—such as economic or climate refugees or those fleeing war—are welcomed by that political order only according to their usefulness. Those seen as threats are contained in prisons and migrant detention centers,

...more

Native people did not become US citizens until 1924. In Canada, we were gradually enfranchised, losing our Indian status if we went to university or fought in the military, and it wasn’t until 1960 that we stopped being “wards of the Crown” and became Canadian citizens.

Race is not biologically real, not in the sense that you can tell somebody’s race by testing their blood or measuring their skull. It’s a social construct, like marriage and citizenship: an idea that got mapped onto humans, replacing relationships with identity and then attaching rights to that identity—rights like who could own land and who could be owned. But people don’t stay in tidy racial categories. People get married. People get raped. Skin color becomes an increasingly unreliable way to decide who belongs in which part of the city and in which kinds of work. So race, like marriage and

...more

Anyone with less than 50 percent blood quantum was given their land outright because they were considered capable of using land in the “correct” way. Those considered “full bloods,” or nearly full bloods, had their allotments held in trust; they were seen as still “too Indian” to be trusted to manage their lands independently and needed federal supervision. So their land would be held in trust for twenty-five years, at which point they were allowed to sell it. The rest of the land in the area subject to allotment was then made available to settlers, who had to meet various criteria to complete

...more

Through the Indian Reorganization Act in the United States and the Indian Act in Canada, governments have imposed not only a kind of leadership that makes sense to them but one that undermines our communities and forces hierarchies of power where they didn’t exist before. That has led to conflicts and corruption in some tribal governments just as we see in American governments.

It is normal to see ourselves in these histories recorded in the Bible, but it is important to think about how we see ourselves and in whom. Too often the descendants of European Christians see themselves as persecuted Israelites rather than as members of the invading state of Babylon: an empire that imposes systems of oppressive leadership over the people of the land for the purpose of control and prosperity.

A relentless ethnic cleansing that began on the East Coast and moved westward as big brother’s hunger for land and resources grew ever more demanding. The US invasion of Mexico in 1846 resulted in the acquisition of almost half of the current US territory. The gold rush in California brought the forty-niners, miners who, despite the romanticized history that has grown up around them, were brutally violent. Later expansions would continue into Alaska and Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines.

A number of years ago, I went to San Antonio, Texas, to see the missions. They are sobering places. The information plaques tell stories of safety and refuge, describing them as places where Native tribes could come for safety from marauding Kiowa or Apache. Those plaques didn’t tell the stories of abuse or why tribes that had found a way to live at peace with each other were now warring again. The plaques didn’t talk about the mission’s own slavery and land theft or the beating and starving of Indigenous people who refused to convert. The plaques were as whitewashed as the buildings.

Names are never neutral; they have something to teach us about our history and how we see ourselves in a place. They create a relationship. Notice the names around you: the places and buildings, the streets and rivers. Google the names of places that intrigue you or are so familiar you barely notice them anymore. What is the history of the names that surround you?

Every American Indian in the United States and Canada has been touched by the residential school system in one way or another. The generational trauma that resulted from decades of this policy is incalculable. There is the loss of language and stories, the loss of relationship. There is the deliberate forgetting of our personal histories to avoid the pain of not forgetting. This destruction of what was ours replaced our languages with French, English, and Spanish; our stories with the Bible; and our systems of kinship with isolated nuclear families. These losses have been woven into our

...more

To be a “person” in the United States and Canada is to be a particular kind of person: somebody who is white and Christian, owns property, holds European values. We may think that this is no longer true today. But 98 percent of private property, 856 million acres of it, in the United States is still owned by white Americans. In fact, just five white people own nine million acres of rural property, which is one million more than all Black Americans own combined.

The Mohawk Institute, founded in 1828, was run by the Anglican Church in the city of Brantford, Ontario, and is just outside the Canadian reserve Six Nations of the Grand River. Considered to be the first residential school to operate in Canada, it remained in operation until 1970. These schools multiplied by the hundreds across the United States and in Canada. Off-reserve education of children was mandatory in the United States until 1978, and although most of the schools have closed, a few remain open. In Canada, the last government-run boarding school closed in 1996, the same year that the

...more

Although the residential school system has ended, many young people in the United States and Canada still need to leave their reservations to go to high school in cities. They stay in boarding homes and dormitories at places like Pelican Falls, youths as young as thirteen in cities for the first time, attending schools far from home.

General Amherst recommended that blankets known to have been used by smallpox victims be distributed to Indians so that they would fall ill as well. His plan may not have been successful, but his willingness to try speaks loudly. Epidemics continued in waves through the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, with consistently inadequate government response and disproportionate impact on Indigenous communities. There are, after all, many ways for people to disappear.

For most people, a home means a father and mother, 2.3 children. The father protects and provides, the mother nurtures and cares, and the children grow up to do it all over again, as Pete Seeger sings, in houses “made of ticky tacky” where they all look “just the same.” These are the family values that America is built on. But whose family is valued, and whose family is removed? Removals of all kinds mean that the homes of Black and Indigenous people, migrants, and those whose religious beliefs placed them outside of Christian norms are kept unstable and precarious.

In the middle part of the century, as the horrors of the German concentration camps were made visible to the world, Canada and the United States began quietly redirecting the horror of residential schools to the more congenial removal of children from their families via the now fully engaged child welfare system. Instead of redcoated RCMP officers working with nuns and priests to tear children from their families, social workers, sometimes with police officers accompanying them, would take children from parents considered neglectful or dangerous and place them with other families. Once again,

...more

Children deserve to be safe. But the language of safety has never meant true safety for Indigenous children. Just as with Indian boarding schools, the vocabulary of “safe” and “educated” and “civilized” has been used to justify war against our communities and to separate us from our families. Policies that define what “acceptable” homes and families look like disrupt our own family and communal practices. After governments and people with good intentions destabilize our communities, the language of safety is used to destabilize them further. If we wanted families to do well, we would put

...more

People think of policing as eternal, as having always existed. But like child welfare and boarding schools, it evolved fairly recently to serve a particular purpose. When you move people off the land, they need to go somewhere, and people without land go to cities. Cities and villages have always had neighborhood watches and loosely organized citizen groups that managed antisocial behavior, but these were local and had limited power. In 1829, Robert Peel created London’s Metropolitan Police Force to deal with the exploding urban population. This