More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

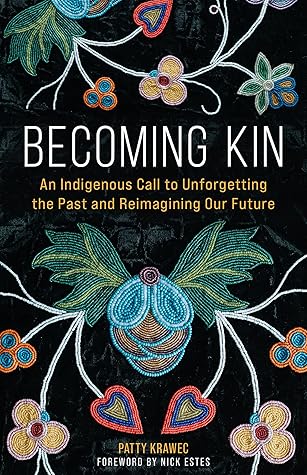

Patty Krawec

without talking about restoring the land to relationship with the people from whom it was taken.

Stones are also our relatives. Whatever I eat has taken up nutrients from the ground, including minerals, and the land itself becomes part of me. Thunderstorms and rivers become part of me. The land and the waters have absorbed the blood and sweat of generations, watched babies become old men and women and return to them. We are part of each other. Civilizations rise and fall, and the land and the waters continue. They hold memory of us all.

ownership itself. And that is interesting to me because by disconnecting inequity from access to land, any social justice action that we take reinforces settler colonialism. We’re simply making settler colonialism fairer and more just, which means that our movements are built on Indigenous erasure.

Notice marginalized people. Notice the land. Notice the agreements. Notice the names. Notice the absences. Notice the gaps.

J. D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy describes Scots-Irish settlers finding belonging in the mountains that reminded them of home—and the way this belonging exists without Indigenous people, who were moved off these mountains, and without Black people, whose labor made these states possible. Vance identifies with a white ethnicity that works to separate itself from the elite but doesn’t recognize its own participation in the erasure of others. Calling his people hillbillies allows them to take on the role of a downtrodden minority without taking responsibility for their role in colonization.

had identity without relationships. That combination—identity with no community—impoverished me. That impoverishment was a constant hum in the background of my life. My face told a story that the rest of me couldn’t articulate except as loss and absence.

Immigrants move into a place and adapt themselves to an existing political system. Settlers impose their own system. Finding home on Indigenous land means living as if this is Indigenous land, not just saying it is.

1.Who used to live in the place where your ancestors lived? Where your church is built? Where your profession emerged and now operates? 2.How did they get displaced? 3.Where are their descendants today?

The Anishinaabe did more than just say they were sorry and expect that to be the end of it. They changed themselves, and they changed the relationship.

There is always possibility for change; in fact, this capacity for change is integral to who we are.

Once we understand the structural nature of what is happening, Augustine writes, we can turn away from individual feelings of guilt for things we didn’t do. Instead, she says, we can engage collectively with others to “dismantle the structures of inequity.”

cannot stress relationships enough. This is important, but it is also not something to be jumped into.