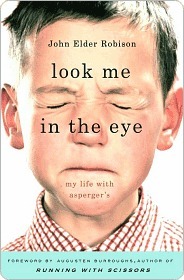

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

November 17 - November 18, 2019

“Ass Burger”)

Everyone thought they understood my behavior. They thought it was simple: I was just no good.

“You look like a criminal.” “You’re up to something. I know it!”

I came to believe what people said about me, because so many said the same thing, and the realization that I was defective hurt.

By then, I knew I wasn’t being shifty or evasive when I failed to meet someone’s gaze, and I had started to wonder why so many adults equated that behavior with shiftiness and evasiveness. Also, by then I had met shifty and scummy people who did look me in the eye, making me think the people who complained about me were hypocrites.

To this day, when I speak, I find visual input to be distracting. When I was younger, if I saw something interesting I might begin to watch it and stop speaking entirely. As a grown-up, I don’t usually come to a complete stop, but I may still pause if something catches my eye.

That’s why I usually look somewhere neutral—at the ground or off into the distance—when I’m talking to someone. Because speaking while watching ...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

And now I know it is perfectly natural for me not to look at someone when I talk. Those of us with Asperger’s are just not comfortable doing it.

SIXTY YEARS AGO, the Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger wrote about children who were smart, with above average vocabulary, but who exhibited a number of behaviors common to people with autism, such as pronounced deficiencies in social and communication skills. The condition was named Asperger’s syndrome in 1981. In 1994, it was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders used by mental health professionals.

When I was a child, mental heath workers incorrectly diagnosed most Asperger’s as depression, schizophrenia, or a host of other disorders.

A February 2007 report from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that 1 person in 150 has Asperger’s or some other autistic spectrum disorder. That’s almost two million people in the United States alone.

Asperger’s is not a disease. It’s a way of being. There is no cure, nor is there a need for one. There is, however, a need for knowledge and adaptation on the part of Aspergian kids and their families and friends.

The fact is, from an evolutionary standpoint, people have an inbred tendency to care about and protect themselves and their immediate family. We do not naturally care about people we don’t know. If ten people get killed in a bus crash in Brazil, I don’t feel anything at all. I understand intellectually that it’s sad, but I don’t feel sad. But then I see people making a big deal over it and it puzzles and troubles me because I don’t seem to be reacting the same way.

For much of my life, being different equated to being bad, even though I never thought of myself that way.

Caring—or pretending to care—about other people is a learned behavior.

I have what you might call “logical empathy” for people I don’t know. That is, I can understand that it’s a shame that those people died in the plane crash. And I understand they have families, and they are sad. But I don’t have any physical reaction to the news. And there’s no reason I should. I don’t know them and the news has no effect on my life. Yes, it’s sad, but the same day thousands of other people died from murder, accident, disease, natural disaster, and all manner of other causes.

As a logical thinker, I cannot help thinking, based on the evidence, that many people who exhibit dramatic reactions to bad news involving strangers are hypocrites. That troubles me. People like that hear bad news from across the world, and they burst into wails and tears as though their own children have just been run over by a bus. To me, they don’t seem very different from actors and actresses—they are able to burst into tears on command, but does it really mean anything?

As I got older, I found myself in trouble more and more for saying things that were true, but that people didn’t want to hear. I did not understand tact. I developed some ability to avoid saying what I was thinking. But I still thought it. It’s just that I didn’t let on quite so often.