More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

May 15 - August 5, 2025

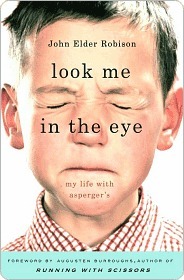

Author’s Note WELCOME TO Look Me in the Eye and my Aspergian world. In this book I have done my very best to express my thoughts and feelings as accurately as possible. I have tried to do the same when it comes to people, places, and events, although that is sometimes more challenging.

In the case of characters that appeared in my brother Augusten Burroughs’s first memoir, Running with Scissors, I have used the same pseudonyms he used.

Foreword by Augusten Burroughs MY BIG BROTHER and I were essentially raised by two different sets of parents. His mother and father were an optimistic young couple in their twenties, just starting out in their marriage, building a new life together. He was a young professor, she was an artistically gifted homemaker. My brother called them Dad and Mamma. I was born eight years later. I was an accident that occurred within the wreckage of their marriage. By the time I was born, our mother’s mental illness had taken root and our father was a dangerous, hopeless alcoholic. My brother’s parents

...more

it’s a bit of an understatement to say there is a history of mental illness in our family, so I was worried that it might be less breakthrough than breakdown.

So, in March 2006, I said to him, “You should write a memoir. About Asperger’s, about growing up not knowing what you had.

Prologue “Look me in the eye, young man!” I cannot tell you how many times I heard that shrill, whining refrain. It started about the time I got to first grade. I heard it from parents, relatives, teachers, principals, and all manner of other people. I heard it so often I began to expect to hear it.

“Nobody trusts a man who won’t look them in the eye.” “You look like a criminal.” “You’re up to something. I know it!” Most of the time, I wasn’t.

“Sociopath” and “psycho” were two of the most common field diagnoses for my look and expression. I heard it all the time: “I’ve read about people like you. They have no expression because they have no feeling. Some of the worst murderers in history were sociopaths.”

To this day, when I speak, I find visual input to be distracting. When I was younger, if I saw something interesting I might begin to watch it and stop speaking entirely. As a grown-up, I don’t usually come to a complete stop, but I may still pause if something catches my eye. That’s why I usually look somewhere neutral—at the ground or off into the distance—when I’m talking to someone. Because speaking while watching things has always been difficult for me, learning to drive a car and talk at the same time was a tough one, but I mastered it.

SIXTY YEARS AGO, the Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger wrote about children who were smart, with above average vocabulary, but who exhibited a number of behaviors common to people with autism, such as pronounced deficiencies in social and communication skills. The condition was named Asperger’s syndrome in 1981. In 1994, it was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders used by mental health professionals.

Many have such exceptional verbal skills that some people refer to the condition as Little Professor Syndrome.

And Asperger’s is turning out to be surprisingly common: A February 2007 report from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that 1 person in 150 has Asperger’s or some other autistic spectrum disorder.

Asperger’s is not a disease. It’s a way of being. There is no cure, nor is there a need for one. There is, however, a need for knowledge and adaptation on the part of Aspergian kids and their families and friends.

It took a long while for me to get to this place, to learn who I am. My days of hiding in the corner or crawling under a rock are over. I am proud to be an Aspergian.

1 A Little Misfit It was inconceivable to me that there could be more than one way to play in the dirt, but there it was. Doug couldn’t get it right. And that’s why I whacked him. Bang! On both ears, just like I saw on The Three Stooges. Being three years old was no excuse for disorderly play habits.

It was the first place where I was thrown together with children I didn’t know. It didn’t go well. At first, I was excited. As soon as I saw the other kids, I wanted to meet them. I wanted them to like me. But they didn’t. I could not figure out why.

The worst of it was, my teachers and most other people saw my behavior as bad when I was actually trying to be kind.

I stopped trying with any of the kids. The more I was rejected, the more I hurt inside and the more I retreated.

I had better luck dealing with grown-ups. My disjointed replies didn’t bring the conversation to an abrupt halt. And I tended to listen to them more than I listened to kids, because I assumed they knew more. Grown-ups did grown-up things. They didn’t play with toys, so I didn’t have to show them how to play.

I still like the feeling of lying under things and having them press on me.

A Permanent Playmate “John Elder, we’re going to move back to Pennsylvania,” my father announced one day when he came home from school.

I figured out how to talk to other children. I suddenly realized that when a kid said, “Look at my Tonka truck,” he expected an answer that made sense in the context of what he had said.

I have since learned that kids with Asperger’s don’t pick up on common social cues. They don’t recognize a lot of body language or facial expressions.

“John Elder, I’m going to have a baby!” my mother said. I didn’t know what to say. Would it be a sister, I wondered? I hoped not. What good would a little sister be? A brother would be better. Yes. A little brother! For me! I would have my own permanent playmate.

for some reason I had a hard time with names, unless I made them up.

I had learned not to reveal anything that might subject me to more ridicule than I already got.

“Your brother is not defective! He’s just a baby. He will be talking just like you in a few years.” My mother continued to stick up for him, even when confronted with the evidence, which annoyed me. After all, he wasn’t talking, and he wasn’t reading. I tried to show him things, but he didn’t seem to study what I showed him. Usually, he put whatever I handed him in his mouth. He would try to eat anything. I fed him Tabasco sauce and he yelled. Having a little brother helped me learn to relate to other people. Being a little brother, Snort learned to watch what he put in his mouth.

Unlike some older brothers, I never set him on fire, or cut off an arm or a leg, or drowned him in the tub.

As I moved through school as another marginal kid, my dad and my teachers started forecasting my future. They told me I would never amount to anything. They said I was headed for a career pumping gas or jail or the Army—if they would take me. I was contrary and I would not apply myself. But I’d show them.

I knew they thought it was bad for me to be smiling, but I didn’t know why I was grinning, and I couldn’t help it.

4 A Trickster Is Born About this time, I figured out one way to capitalize on my differences from the mass of humanity. In school, I became the class clown. Out of school, I became a trickster.

I read all the time, and I was learning all sorts of new things. In fact, I kept the more interesting volumes of the Encyclopaedia Britannica next to my bed.

People began looking at me and listening to me as if I was a prodigy.

They saw how often I was right, and they heard the certainty in my voice when I said things. It seemed to be a case of “say it and it must be so.”

“And that bright star—that’s Sirius, the Dog Star. And that one there, that’s Bovinius, the Cow Star.” “Are you pulling my leg, John Elder? I never heard of the Cow Star.” My grandparents were skeptical. “I read about it in my book of mythology. The one you bought me. Cows are sacred in India, and that’s their star. Wanna read about it?” “No, son, I’m sure you’re right.”

By this time in my life, I had gotten to know many of the lowlifes that hung around downtown during the day. Rug, Stump, Fatso, and Freddie. And Willie the bookie and Charles the pimp.

I got Fs in all my courses by that time. Failing grades didn’t scare me anymore.

I spent countless hours restoring that old Porsche. I rebuilt the engine, and then rebuilt the body. I probably removed and repaired every single part of that car,

one day, I realized that there was a fundamental problem with my Porsche: There was nothing left to fix. So I sold it and found another Porsche to restore, a gray 911E. Since that day, I’ve owned seventeen Porsches, and I’ve fixed up or restored every single one. Even when I had money, I never bought new cars. Any fool with money can buy a new Porsche, I thought. It takes a craftsman to restore an old one. And that’s what I dreamed of being. A craftsman. An artist, working in automotive steel.

The Nightmare Years A dark cloud slid over our family about the time we moved to Shutesbury. There were some bright spots—the woods and my Porsche, for example—but things were spiraling out of control with my parents.

my father didn’t like Snort too much, back in those days.

One night, he called my brother instead of me. “Commere, little Chris,” he said, slurring his words. My brother was too small to mistrust him. Stupid kid. He went closer, and my father grabbed him. Set him on his knee. It looked so harmless. Just a brainless, smiling toddler, sitting on daddy’s lap. He sat there a few minutes and nothing happened. I relaxed a little. Snort was smiling. Then daddy reached down and mashed his cigarette out. In the middle of Snort’s forehead. My little brother screamed.

Still, for some inexplicable reason, I did well in school—better than I had ever done, or would ever do again. When I graduated from sixth grade, our class had seven achievement prizes. I won six of them.

Both my parents had gone from bad childhoods to a bad marriage, and now I was living with the result.

Our father would have been enough for any family, but we had my mother, too. By this time, she had begun the slow slide into madness that would eventually send her to the Northampton State Hospital in restraints. She started seeing things overhead. Demons, people, ghosts … I never knew who or what she saw. They were in the light fixtures, in the corners, or on the ceiling. “Don’t you see them?” she would ask. I never did. Some of the things she said were so disturbing, I blocked them from my mind and can’t repeat them today. My memories of that time are like blinding flashes of harsh, actinic

...more

My mother would say, “John Elder, your father is a very smart, very dangerous man. He’s too smart for the doctors. He fools them into thinking he’s normal. I’m afraid your father is going to try and kill us. We need to hide. We need to get away from him until the doctor can get him under control.”

By the time I turned thirteen and my brother was five, my mother had found the Dr. Finch that my brother wrote about in Running with Scissors.

shortly after we started seeing him, Dr. Finch did two things that changed my life: He told me I could call my parents anything I wanted, and he told my father that he could not smack me around.

“I have decided to name you Slave,” I said, looking at my mother. “And your name is Stupid,” I told my father.

Dr. Finch may not have known about Asperger’s, but he was the first person to support and encourage my naming of things on my own.