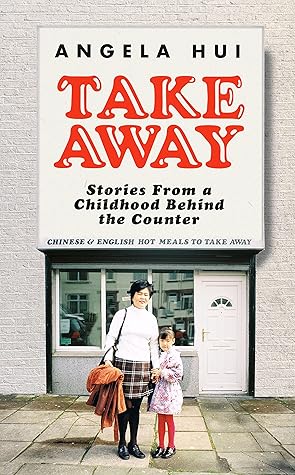

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Angela Hui

Read between

August 17 - August 21, 2022

In March 2020 (when the first UK lockdown began), the Metropolitan Police reported a sharp spike in anti-Asian hate crimes, coinciding with the Covid-19 pandemic. Reported incidents increased by 179% and were 2.79 times greater than the number reported in the previous year.

Being Chinese, I’m technically a minority that’s privileged, but excluded. East and Southeast Asians are considered so white-adjacent that they are no longer identified as a person of colour, but still experience systemic racism.

It was a juxtaposition of us being treated like immigrants, but also being keepers of something instinctively British.

More often than not you’ll find a jade plant with its bulbous green leaves pushing up against the front window near the entrance of any Chinese takeaway to keep the waiting room lively. Strategically placed in a southeast location for feng shui that brings the owner prosperity and success, the plant reflects vibrant, well-rooted energy. It is vital for newfound money, which is precisely why my parents had two to ensure maximum profits.

There’s a familiar look and feel to most Chinese takeaways up and down the country in the UK. They all look the same from an outsider’s perspective, but look a little deeper – beyond the plants, fish tanks, lanterns and menu boards – and you’ll find the people that work behind the counter have their own stories and personalities that they project into their business.

The customer: independent and free to do whatever and order whatever. The worker: constrained and chained to the shackles of the takeaway. We’re both humans, the only difference is one is standing on one side of the giant plank of wood running across the room and the other behind it. This makes the us-versus-them divide even bigger, and the counter itself is the symbol of otherness. It’s the first thing customers see when they enter the takeaway, and the last thing they see when they leave.

‘Aw, maths, is it? Maybe I can help?’ He peers over the counter nosily. ‘I’ll have you know, not only have I got the looks, I’ve also got the brains! Bahaha! Stuck, are you? You’re Asian, you’re supposed to be good at maths, you know.’

After a while, the anxiety from not being able to communicate with my parents and having to switch between two languages – and two versions of myself – led to a spiral of behavioural change. Outside the takeaway: chirpy, bright and friendly Welsh Angela; during service: anxious, sulky and miserable Chinese Angela.

Though words don’t come easy to us, our language is food and we mainly only interact around food. In Chinese culture, we don’t greet each other by saying ‘hello’, we ask whether ‘Sik jor fan mei ah?’ (食咗飯未呀?), which means ‘Have you eaten yet?’ Probably one of the most important phrases in the Chinese language.

The only way to determine whether or not someone is a true Hongkonger is not judging them by what they order, but by whether or not they drink the water on the table that’s intended for cleaning.

Soon, we fall madly in love and become best friends. He makes me laugh like no one else I’ve ever met and being with him is like being in a warm bath.

Mum rejected surgery, even against everyone’s wishes, showing me it’s okay to do what’s right for you and leave situations which, for one reason or another, no longer serve you.