More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

I am not granite and should not be taken for it.… Granite does not accept footprints. It refuses them. Granite makes pinnacles, and then people rope themselves together and put pins on their shoes and climb the pinnacles at great trouble, expense, and risk, and maybe they experience a great thrill, but the granite does not. Nothing whatever results and nothing whatever is changed.… I have been changed. You change me. Do not take me for granite.1

In one sense, I read this too late—too late to write to Le Guin and tell her everything it had made me feel, how much it made me want to live my life by its light. But in another, I felt as if I was at last coming into alignment with Le Guin—that I was reading the right thing of hers at the right time to fall completely in love. It was almost like a meeting: hearing her voice clear and true, speaking through an old woman’s mouth and ringing in my heart like a bell.

Le Guin observes the nature of lineage and community by this uncanny, implacable light, never forgetting the human scale of a lifetime before obliterating it.

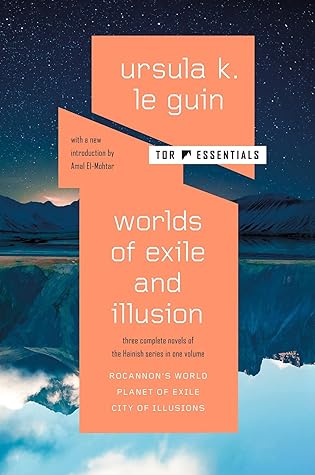

“Most of my stories,” Le Guin writes in her own introduction to City of Illusions, “are excuses for a journey. I never did care much about plots, all I want is to go from A to B—or, more often, from A to A—by the most difficult and circuitous route.”

Le Guin also wrote that she could see in Rocannon’s World “the timidity, and the rashness, and the beginner’s luck, of the apprentice demiurge … I certainly couldn’t write it now, but I can read it; and the thirteen-year distance lets me see, peacefully, what isn’t very good in it, and what is.… And it has a good shape.”

But while one needs an ansible to speak to the vanishing past, books are the technology we have to speak to the future, collapsing space and time into the simple honesty of an aging woman’s voice, telling the story of her earliest stories.

Unreason darkens that gap of time bridged by our lightspeed ships, and in the darkness uncertainty and disproportion grow like weeds.

There’s no room at Kirien for girls and gold and all the rest of the story. The story’s over here; this is the fallen place, this is the empty hall. The sons of Leynen all are dead, their treasures are all lost. Go on your way, girl.”

“It is not here.” “Then it is elsewhere.” “It is where you cannot come to it. Never, unless we help you.”

The lords to whom you, the proud Angyar, pay tribute, are our friends. They do us favors as we do them favors! Now, what do your thanks mean to us?” “That is your question to answer,” said Semley, “not mine. I have asked my question. Answer it, Lord.”

“What I feel sometimes is that I … meeting these people from worlds we know so little of, you know, sometimes … that I have as it were blundered through the corner of a legend, of a tragic myth, maybe, which I do not understand.…”

For to an aggressive people only technology mattered.

Other races on other worlds could be pushed ahead faster, to help when the extra-galactic enemy returned at last. No doubt this was inevitable. He thought of Mogien offering to fight a fleet of lightspeed bombers with the swords of Hallan. But what if lightspeed or even FTL bombers were very much like bronze swords, compared to the weapons of the Enemy?

What if the weapons of the Enemy were things of the mind? Would it not be well to learn a little of the different shapes minds come in, and their powers?

The way the Angyar talked was a real pleasure, Rocannon thought, though its tact was not what struck you.

In times like this, Mogien, one man’s fate is not important.” “If it is not,” said Mogien, raising his dark face, “what is?”

They were a boastful race, the Angyar: vengeful, overweening, obstinate, illiterate, and lacking any first-person forms for the verb “to be unable.” There were no gods in their legends, only heroes.

The world itself has become a grain of sand on the shore of night.

Swayed by his companions’ genuine courage, he had been ashamed to wear his protective and almost invisible impermasuit for this foray. Owning armor that could withstand a laser-gun, he might die in this damned hovel from the scratch of a bronze-headed arrow. And he had set off to save a planet, when he could not even save his own skin.

They drank. Rocannon began to feel better. Mogien inquired of his wound, and Rocannon felt much better.

Rocannon knew the man would have given half his flocks and wives to be rid of his unearthly guest, but was trapped in his own cruelty: the jailer is the prisoner’s prisoner.

“You’re not master here. The lawless man is a slave, and the cruel man is a slave, and the stupid man is a slave. You are my slave, and I drive you like a beast. Out!”

What was a wizard without his staff? “Well,” he said, “it’s a good walking-stick, if we’ve got to walk.”

“Hanh, hanh,” the wild man went, still troubled, but a genial streak in him seemed to win out over his fears.

They saw no other living thing. Clear to the sky the high grasslands stretched, level, treeless, roadless, silent. Oppressed by immensity, the two men sat by their tiny fire in the vast dusk, saying nothing.

“You’ve seen many worlds,” the young man said dreamily, trying to conceive of it. “Too many,” said the older man. “I’m forty, by your years; but I was born a hundred and forty years ago. A hundred years I’ve lost without living them, between the worlds. If I went back to Davenant or Earth, the men and women I knew would be a hundred years dead. I can only go on; or stop, somewhere—

“You greeted the Kiemhrir as if you knew of them,” Rocannon observed, and the Fian answered: “What one of us in my village remembered, all remembered, Olhor. So many tales and whispers and lies and truths are known to us, and who knows how old some are.…” “Yet you knew nothing of the Winged Ones?” It looked as if Kyo would pass this one, but at last he said, “The Fiia have no memory for fear, Olhor. How should we? We chose. Night and caves and swords of metal we left to the Clayfolk, when our way parted from theirs, and we chose the green valleys, the sunlight, the bowl of wood. And therefore

...more

“Each day as we travel southward I ride into the tales that my people learn as little children, in the valleys of Angien. And all the tales I find true. But half of them all we have forgotten. The little Name-Eaters, the Kiemhrir, these are in old songs we sing from mind to mind; but not the Winged Ones. The friends, but not the enemies. The sunlight, not the dark. And I am the companion of Olhor who goes southward into the legends, bearing no sword. I ride with Olhor, who seeks to hear his enemy’s voice, who has traveled through the great dark, who has seen the World hang like a blue jewel in

...more

“Among your people, Kyo, did you bear no name of your own?” “They call me ‘herdsman,’ or ‘younger brother,’ or ‘runner.’ I was quick in our racing.” “But those are nicknames, descriptions—like Olhor or Kiemhrir. You’re great namegivers, you Fiia. You greet each comer with a nickname, Starlord, Swordbearer, Sunhaired, Wordmaster—I think the Angyar learned their love of such nicknaming from you. And yet you have no names.” “Starlord, far-traveled, ashen-haired, jewel-bearer,” said Kyo, smiling;—“what then is a name?”

My name given me at birth was Gaverel Rocannon. When I’ve said that, I’ve described nothing, yet I’ve named myself. And when I see a new kind of tree in this land I ask you—or Yahan and Mogien, since you seldom answer—what its name is. It troubles me, until I know its name.”

“Well, it is a tree; as I am a Fian; as you are a … what?” “But there are distinctions, Kyo! At each village here I ask what are those western mountains called, the range that towers over their lives from birth to death, and they say, ‘Those are mountains, Olhor.’” “So they are,” said Kyo. “But there are other mountains—the lower range to the east, along this same valley! How do you know one range from another, one being from another, without names?” Clasping his knees, the Fian gazed at the sunset peaks burning high in the west. After a while Rocannon realized that he was not going to answer.

“It was foretold that the Wanderer would choose companions. For a while.” He did not know if he had spoken, or Kyo, or his memory. The words were in his mind and in Kyo’s. The dancers broke apart, their shadows running quickly up the walls, the loosened hair of one swinging bright for a moment. The dance that had no music was ended, the dancers that had no more name than light and shadow were still. So between him and Kyo a pattern had come to its end, leaving quietness.

A man can die anywhere, but his own death, his true death, a lord meets only in his domain. It waits for him in the place which is his, a battlefield or a hall or a road’s end. And this is my place. From these mountains my people came, and I have come back. My second sword was broken, fighting. But listen, my death: I am Halla’s heir Mogien—do you know me now?”

What do you give for what I have given you? What must I give, Ancient One? That which you hold dearest and would least willingly give. I have nothing of my own on this world. What thing can I give? A thing, a life, a chance; an eye, a hope, a return: the name need not be known. But you will cry its name aloud when it is gone. Do you give it freely? Freely, Ancient One.

With Kyo he had had some beginnings of mindspeech; but he did not want to know his companions’ minds when they were ignorant of his. Understanding must be mutual, when loyalty was, and love.

But those who had killed his friends and broken the bond of peace he spied upon, he overheard. He sat on the granite spur of a trackless mountain-peak and listened to the thoughts of men in buildings among rolling hills thousands of meters below and a hundred kilometers away. A dim chatter, a buzz and babble and confusion, a remote roil and storming of sensations and emotions. He did not know how to select voice from voice, and was dizzy among a hundred different places and positions; he listened as a young infant listens, undiscriminating. Those born with eyes and ears must learn to see and

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Rain pattered hard on a raftered roof. The air of the room was dark and clear. Near his couch stood a woman whose face he knew, a proud, gentle, dark face crowned with gold. He wanted to tell her that Mogien was dead, but he could not say the words. He lay there sorely puzzled, for now he recalled that Haldre of Hallan was an old woman, white-haired; and the golden-haired woman he had known was long dead; and anyway he had seen her only once, on a planet eight lightyears away, a long time ago when he had been a man named Rocannon.

O lovely wrath, Rocannon thought, hearing the trumpets of lost Hallan in her voice. “They will pay, Lady Ganye; they will pay a high price. Though you knew I was no god, did you take me for quite a common man?” “No, Lord,” said she. “Not quite.”

The incident on the mountainside had warned him that at close range sensitive individuals might become aware of his presence, though in a vague way, as a hunch or premonition.

But to fly them was to commit suicide; no life survived a faster-than-light “trip.” So each pilot was not only a highly trained polynomial mathematician, but a sacrificial fanatic. They were a picked lot.

He had done what he could do. He had been a fool to think he could do anything. What was one man alone, against a people bent on war?

“Will your own people not come to seek you?” He looked out over the lovely country, the river gleaming in the summer dusk far to the south. “They may,” he said. “Eight years from now. They can send death at once, but life is slower.… Who are my people? I am not what I was. I have changed; I have drunk from the well in the mountains. And I wish never to be again where I might hear the voices of my enemies.”

“Stay with us here.” Rocannon paused a little and then said, “I will. For a while.” But it was for the rest of his life. When ships of the League returned to the planet, and Yahan guided one of the surveys south to Breygna to find him, he was dead. The people of Breygna mourned their Lord, and his widow, tall and fair-haired, wearing a great blue jewel set in gold at her throat, greeted those who came seeking him. So he never knew that the League had given that world his name.

He recognized the turn of her head and smile. She was the one he teased, the one that was indolent, impudent, sweet-natured, solitary; the child born out of season. What the devil was her name?

She looked to be about twenty moonphases old, which meant she was the one born out of season, right in the middle of the Summer Fallow when children were not born. The sons of Spring would by now be twice or three times her age, married, remarried, prolific; the Fall-born were all children yet. But some Spring-born fellow would take her for third or fourth wife; there was no need for her to complain. Perhaps he could arrange a marriage for her, though that depended on her affiliations. “Who is your mother, kinswoman?”

If Wold did not ask him to be seated in front of the other humans, he would not be seated when there were none to see. Wold did not think all this nor decide upon it, he merely sensed it through a skin made sensitive by a long lifetime of leading and controlling people.

That he was a homosexual and that Agat was not was a fact well-known to them both, to everybody around them, to everyone in Landin indeed. Everybody in Landin knew everything, and candor, though wearing and difficult, was the only possible solution to this problem of over-communication.

The talk became general, though it tended always to center around and be referred back to Jakob Agat. He was younger than several of them, and all ten Alterrans were elected equal in their ten-year terms on the council, but he was evidently and acknowledgedly their leader, their center. No especial reason for this was visible unless it was the vigor with which he moved and spoke; is authority noticeable in the man, or in the men about him? The effects of it, however, showed in him as a certain tension and somberness, the results of a heavy load of responsibility that he had borne for a long

...more

The cup in his hand, blue porcelain, was very old, a work of the Fifth Year. The handpress books in cases under the windows were old. Even the glass in the windowframes was old. All their luxuries, all that made them civilized, all that kept them Alterran, was old. In Agat’s lifetime and for long before there had been no energy or leisure for subtle and complex affirmations of man’s skill and spirit. They did well by now merely to preserve, to endure.

Gradually, Year by Year for at least ten generations, their numbers had been dwindling; very gradually, but always there were fewer children born. They retrenched, they drew together. Old dreams of dominion were forgotten utterly. They came back—if the Winters and hostile hilf tribes did not take advantage of their weakness first—to the old center, the first colony, Landin. They taught their children the old knowledge and the old ways, but nothing new. They lived always a little more humbly, coming to value the simple over the elaborate, calm over strife, courage over success. They withdrew.