More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

January 5 - January 19, 2025

But when it comes down to it, I’m so amazed by the true and recorded history I discover that it seeps into my dreams and acquires, without my volition, the shape of a story. I’m tempted to step into the skin of those who traveled the roads of an ancient, violent, tumultuous Europe in pursuit of books.

but historical documents show that in the megalomaniacal minds of the kings of Egypt, it was truly possible. It might have been the last and only time—there, in the third century BC—that the dream of gathering all the books in the world, without exception, in a universal library, could become a reality.

In the words of Umberto Eco, the book belongs to the same category as the spoon, the hammer, the wheel, or a pair of scissors. Once invented, these things cannot be surpassed.

He felt the same reverence for Achilles that boys today feel for their sports heroes. It’s said that Alexander always slept with his copy of The Iliad and a dagger under his pillow.

There is a word in Greek that describes his obsession: póthos. It is the desire for something absent, something that lies beyond reach, a desire that causes suffering since it is impossible to fulfill.

We know it as The Alexander Romance, and it has reached our times with a series of variations and omissions. Some scholars believe that aside from certain religious texts, this outlandish and far-fetched work was the most widely read book in the premodern world.

“The Earth,” Alexander proclaimed in one of the first decrees he issued, “I consider mine.” Bringing together all existing books is another—symbolic, intellectual, peaceful—way of possessing the world.

The young king who married three foreign women and had semi-barbarian children was planning, according to the historian Diodorus, to transplant the population of Europe to Asia and vice versa, to build a community of friendship and family between continents. His sudden death prevented him from carrying out this project of mass immigration and deportation, a peculiar combination of violence and humanitarian zeal.

The Library made the best part of Alexander’s dream come true: his universalism, his passion for knowledge, his unprecedented desire for fusion. On the shelves of Alexandria, borders were dissolved, and the words of the Greeks, the Jews, the Egyptians, the Iranians, and the Indians finally coexisted in peace.

Even Borges was bewitched by the idea of possessing all the books in existence. His story “The Library of Babel” takes us into a prodigious library, a labyrinth encompassing all dreams and words.

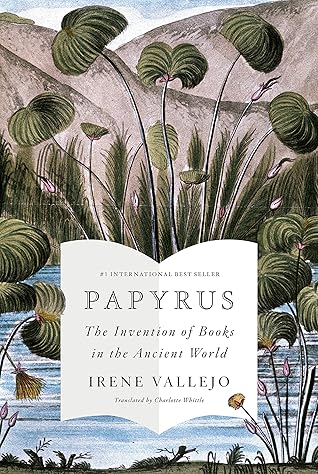

Egypt exported the most widely used writing material of the period: papyrus.

The kings of Egypt developed a monopoly over its manufacture and trade; experts in the Egyptian language believe that “papyrus” and “pharaoh” share the same root.

The papyrus scroll represented an extraordinary amount of progress. After centuries of searching for the right format, of humans writing on stone, mud, wood, or metal, language had finally found its home in organic matter. The first book in history was born when words—as ethereal as air—found refuge in the pith of an aquatic plant.

There, Alexander was visited by the first Roman emperor, Augustus, who laid a garland upon the glass cover of the sarcophagus and asked to touch the body. Gossiping tongues would claim that when the emperor kissed the corpse, he accidentally broke its nose—kissing a mummy entails a certain amount of risk.

The new chief of book acquisition and management was Demetrius of Phalerum. He invented the hitherto nonexistent position of librarian.

Demetrius brought to Egypt the Aristotelian model of thought, which in those days was on the cutting edge of Western science. It was said that Aristotle had taught the Alexandrians how to organize a library.

Demetrius sent agents, saddled with supplies and armed to the hilt, to Anatolia, the islands of the Aegean Sea, and Greece, to hunt down works in Greek.

That proto-globalization was known as Hellenism. Customs, beliefs, and common ways of life took root in the territory conquered by Alexander from Anatolia to the Punjab. Greek architecture was imitated in places as remote as Libya and the island of Java.

Many Greeks, who for centuries had lived in small cities run by their own citizens, saw themselves suddenly incorporated into large kingdoms. A sense of uprootedness began to spread, a feeling of displacement, of being lost in a universe that was too large, governed by distant, inaccessible powers. Individualism developed; loneliness became more acute.

Ptolemy’s Musaeum went further: it was one of Hellenism’s most ambitious institutions, an early version of the research centers, universities, and think tanks we know today. The greatest writers, poets, scientists, and philosophers of the era were invited to the Musaeum.

You have created a parallel world like the illusion of cinema, a world that depends on you alone. At any moment, you can avert your gaze from these lines and return to the action and movement of the outside world. But in the meantime, you remain on the edge, in the place where you’ve chosen to be. There is an almost magical aura to the act of reading.

I’m always excited to be in places where something happened for the first time, in the territory of new beginnings.

Museums have been described as “the cathedrals of the twenty-first century.”

Invented five thousand years ago, the books we are speaking of, in fact the ancestors of books and of the electronic tablets we use today, were tablets made of clay. There were no papyrus reeds on the riverbanks of Mesopotamia, and while other materials such as stone, wood, and animal skin were scarce, clay was abundant.

Books conceal incredible tales of survival. On rare occasions—the fires of Mesopotamia and Mycenae, the rubbish dumps of Egypt, the eruption of Vesuvius—destructive forces have saved them.

Beginning with the edict of Theodosius I in the year 380, Christianity became the compulsory state religion, and pagan cults were prohibited in the Roman Empire.

the Rosetta Stone would open the door to the lost language of ancient Egypt. The adventure of deciphering it awakened a new interest in cryptography, which in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would grip the imagination of Edgar Allan Poe in his story “The Gold-Bug,”

And after reading Akhmatova’s poem, I can no longer help it: Assyrian tablets remind me of the faces of those who have lived and suffered greatly.

Even the most highly trained, attentive person might make mistakes (misreadings, lapses due to fatigue, mental translations, misinterpretations and mistaken corrections, substituted words, jumps in the text). In fact, the copyist’s personality is portrayed in the mistakes he makes.

They observed that the process of successive copies was stealthily altering their literary content. In many passages, what the author was trying to say couldn’t be understood, and in other places, lines varied according to the copy. When they realized the extent of the problem, they understood that over the centuries, just as rocks are eroded by the constant rush of waves, texts would be eroded by the silent force of human fallibility, and the stories would become more and more incomprehensible, until they no longer made any sense at all.

He is a name without a life story, or perhaps just the nickname of a blind poet—the name Homer can be translated as “he who does not see.” The Greeks knew nothing certain about him and couldn’t even agree when they tried to assign him a date.

Papyruses unearthed in Egypt confirm that The Iliad was by far the most read Greek book of ancient times, and passages from the poems have been discovered in the sarcophagi of Greco-Egyptian mummies—people who took Homeric verses with them on their voyage to eternity.

Until that moment, the oral poem was a living organism that grew and changed, but writing would calcify it. Elevating only one version of the story meant sacrificing all others, but at the same time, it meant saving it from being destroyed and forgotten.

Even the most innovative literary work always contains fragments and traces of countless earlier texts.

Those wandering artists dressed in rags, sent by the Muses, those wise bohemians who explained the way of the world in song—half encyclopedists, half jesters—are the ancestors of writers. Their poetry came before prose, and their music before silent reading. A Nobel Prize for oral culture. How ancient the future can sometimes be.

To an Egyptian scribe accustomed to using hundreds of signs, using fewer than thirty letters to represent all the words in the language would seem a coarse method. He would have sneered and raised his eyebrows at our uninspiring “E,” derived from a beautiful Egyptian hieroglyph—a man lifting his arms—which bore the poetic meaning: “Your presence brings joy.”

The few—if any—copies that were made barely circulated. There is therefore no trace of a book trade or industry in the archaic period.

Socrates feared that, with writing, men would abandon the effort of thought itself. Knowledge, he suspected, would be entrusted to texts, and it would be enough to have them within reach without bothering to truly understand them.

Perhaps letters are merely dead and spectral signs, illegitimate children of the spoken word, but as readers, we know how to breathe life into them. I would love to tell this story to that old curmudgeon Socrates.

Writing and memory are not adversaries. In fact, throughout history, each one has saved the other: words protect the vulnerable past; memory protects persecuted books.

Heraclitus believed reality could be explained as permanent tension. He called it “war,” or a struggle between opposites. Day and night, wakefulness and sleep, life and death: all these become each other and can only exist in opposition; they are fundamentally two sides of the same coin.

The echoes of this constellation of words have still not faded. The word “encyclopedia” incorporates the ancient paideia and descends from the expression en kyklos paideia, which can still be heard today in the global polyglot experiment of Wikipedia.

Though the fact has gone somewhat unnoticed, libraries are one of the ancient phenomena to have colonized us most effectively.

In her most intimate, best-known hymn, she reveals the secret of her creative process: the goddess of the moon visits her home at midnight and helps her “conceive” new poems, “delivering” verses that live and breathe. It’s a magical, erotic, nocturnal happening. As far as we know, Enheduanna was the first person to describe the mysterious birth of poetry.

We should not forget that Athenian democracy was founded on the exclusion of all women, and of foreigners and slaves—in other words, of most of the population.

On the coast of Anatolia and the nearby Aegean islands (Lesbos, Chios, Samos…), a land of Greek emigrants on the Asian border, there was another, more open world. Prohibitions were less strict in those parts and confinement less suffocating.

Women writers had to face the threat of mockery, of a mirror that distorted their reflection. Perhaps that’s why they loved secrecy, the power of suggestion, riddles, questions.

It’s thought, though this is mere conjecture, that these circles were thiasi for women, a kind of religious club where adolescents, under the guidance of a charismatic woman, learned poetry, music, dancing, honored the gods, and perhaps engaged in erotic exploration before they were married.

In a fragment of just one line, which has reached us by chance, we read, “I declare that someone will remember us.” And though that chance seemed almost nonexistent, almost thirty centuries later, we can still hear the voice of that diminutive woman.

Almost five centuries later, the historian Plutarch transcribes a string of insults against the subversive Athenian first lady taken from writings of the period, where she is called immodest, a bitch-faced concubine, and a brothel keeper, among other charming labels.