More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

You can hand the knife to another person, betting with yourself how deep a wound he or she is willing to inflict. You can be the inflicter of the wound.

My first reaction, after I read the postscript: I wanted to get pregnant right away. I would carry a baby to term and I would give birth to a child without dying myself—I knew this with the certainty that I knew my name. This would be proof that I could do something Fabienne could not—be a bland person, who is neither favored nor disfavored by life. A person without a fate.

Earl loves me, and I love being married to him. The fact that he cannot give me a child may be disheartening to him, but I have told him that I did not marry him to become a mother. In any case we are both realists.

He is a loving husband, but love does not often lead to perception. When I met him, he thought I was a young woman with no secrets and few stories from my childhood and girlhood. Perhaps it is not his fault that I cannot get pregnant. The secrets inside me have not left much space for a fetus to grow.

No, it is not Fabienne’s ghost that has licked the nib of my pen clean, or opened the notebook to this fresh page, but sometimes one person’s death is another person’s parole paper. I may not have gained full freedom, but I am free enough.

They went away, they came back, and what happened in between was no one’s business. Our happiness should not be rooted and immobile.

The questions that did not occur to me to ask at thirteen feel important now. I wonder if Fabienne knew the answers. I wish I could ask her. This is the inconvenience of her being dead. Half of this story is hers, but she is not here to tell me what I have missed.

How do I measure Fabienne’s presence in my life—by the years we were together, or by the years we have been apart, her shadow elongating as time goes by, always touching me?

If I lie on Fabienne’s stone, I wonder if I will feel the same heaviness as we once did. There will be no waiting for her to decide when to stand up and walk away. Any choice will have to be mine: to up and leave, or to remain immobile above her grave forever.

Later, some people are smart enough to turn themselves into myths. Some people turn others into myths. Yet what is myth but a veil arranged to cover what is hideous or tedious?

What’s the difference between knowing a story and writing it out? But the questions I should have asked, which I did not know how when we were younger, were: Isn’t it enough just to know a story? Why take the time to write it out? I now have the answer, for her and for myself. The world has no use for who we are and what we know. A story has to be written out. How else do we get our revenge? (Revenge against what, or whom, precisely? Don’t, Agnès, fall into the trap and answer that question.)

The three of us made a volatile triangle. I, Agnès, would be just fine with only Fabienne in my life, but she needed more than I could give her. M. Devaux was not much, but there were things he offered Fabienne that I could not.

And you’d also remember that we wasted nothing that had once lived, after it died. There were always hungry creatures waiting to eat so that they could postpone being eaten themselves.

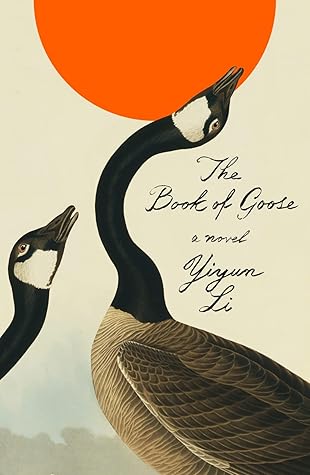

From life to life? That is a long way. The cousins of my geese, the wild ones, fly over a continent. People leave their homes for new homes, new cities, new countries. But who can shorten the distance between two people so they can say with confidence that they have reached each other? In that sense perhaps Fabienne was one of the few who worked miracles. She made me her. She made us into one person.

I could be myself only when I was with Fabienne. Can a wall describe its own dimensions and texture, can a wall even sense its own existence, if not for the ball that constantly bounces off of it?

We forgive many people for what they cannot do for us, but not our mothers; we protect our mothers more than we protect others, too. Sometimes I think it may be just as well that I cannot have my own children: I can count more things I would not be able to do for them than what I could; and I would rather march through life without the futile protection from my children. People often forget that it is always a gamble to be a mother; I am not a gambler.

Would she think herself too greedy, asking god to spare both of her children? Would she trade one for the other? If I were a fair god, I would take Jean; Gisele had five children, and they all needed her.

Perhaps they were two equals, and I was only half of what they were. That thought bothered me for a few days, until I found a way to convince myself that it was not true. M. Devaux might know more about the world than I did, but he did not know the secret of being Fabienne’s true friend: to stay still in her shadow, to be as empty as the air around her, and to be everywhere with her.

I hesitated. “I would watch you being an author and I would be happy.” “No, you would be sad,” Fabienne said. “I would?” “Yes,” Fabienne said. “Because you would have no part in the game. The books would have nothing to do with you. And what happened to me would have nothing to do with you. Don’t you see?”

We were the perfect pair, one seeking all that the other could experience.

Happiness, I would tell her, is to spend every day without craning one’s neck to look forward to tomorrow, next month, next year, and without holding out one’s hands to stop every day from becoming yesterday.

I was imagining a person who was half Fabienne and half Agnès, and I had no trouble stepping into the shoes of that person.

These questions, seemingly innocuous, are more unreasonable than people realize. If you asked a cow, or a pig, or a chicken what it wanted to do with its life, it would have no idea how to answer, even if by some miracle it could understand and speak our language. If you asked a cow, or a pig, or a chicken how it would like to die, it would not fare any better.

Life is most difficult for those who know what they want and also know what makes it impossible for them to get what they want. Life is still difficult, but less so, for those who know what they want but have not realized that they will never get it. It is the least difficult for people who do not know what they want.

Some, like me, can commit to anything, which is like committing to nothing. Perhaps that is why my American relatives call me passive.

Often I imagine that living is a game of rock-paper-scissors: fate beats hope, hope beats ignorance, and ignorance beats fate.

It baffles me that often songs and poems are written about love at first sight: those who claim to experience the phenomena have preened themselves, ready for love. There is nothing extraordinary about that. Childhood friendship, much more fatal, simply happens.

Fabienne turned to me and touched my cheek with the back of her hand. “Agnès, poor you, I can see Paris hasn’t made you smarter.” The gentleness in her gesture made me mad. What was wrong with her?

Fabienne and I were in this world together, and we had only each other’s hands to hold on to. She had her will. I, my willingness to be led by her will.

“We can find work there,” I said. “And we can live together.” “Just the two of us?” “Yes,” I said. “We don’t need anyone else, do we?” Fabienne looked at me strangely. It was not one of her usual looks, teasing, or contemptuous, or mockingly affectionate. I knew every expression on her face as she knew every thought on my mind. But now her eyes betrayed something else. Alarm. Incredulity. Even hostility.

“The problem with you,” she said, “is that you don’t think much and you don’t feel much, so you’re easily amused and satisfied.” “I don’t think much because you’re doing the thinking for me,” I said. “Exactly,” Fabienne said. “I don’t mind thinking for both of us, but what can you do for me?”

“No. You and I are like day and night.” “What do you mean?” “Is there an hour that is neither day nor night?” she said. “No. So you see, you and I together, we cover all the time, we have everything between us.”

He would never call me an imbecile, and he would be willing to listen to me a little more than she did. He might even love me. And the best part, of course, was that he was really Fabienne. Perhaps he would make it easy for me to say things that I had never said to her. Perhaps she would feel the same, too, saying to me things she would never say as Fabienne.

People like Mrs. Townsend, who are obsessed with keeping a full account of their lives, are like artists who create optical illusions. A year is a year anywhere, a day is a day for everyone, and yet with a few tricks these archivists make others believe that they have packed something into their days, something precious, enviable, everlasting, that is not available to everyone.