More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

He is a loving husband, but love does not often lead to perception. When I met him, he thought I was a young woman with no secrets and few stories from my childhood and girlhood. Perhaps it is not his fault that I cannot get pregnant. The secrets inside me have not left much space for a fetus to grow.

sometimes one person’s death is another person’s parole paper. I may not have gained full freedom, but I am free enough.

Happiness should not be dirt-colored and hidden underground. Even apples on a branch would be better suited to be called happiness than apples in the earth. Though if happiness were like apples, I thought, it would be quite ordinary and uninteresting.

You had to believe that god existed so you could make mischief and upend his plans.

“If we can grow happiness, can we also grow misery?” I asked her. “Do you grow thistles or ragworts?” Fabienne said. “Do you mean misery grows by itself, like thistles and ragworts?” “Or by god,” Fabienne said. “Who knows?” “But happiness, can it grow by itself?” “What do you think?” “I think happiness should be like thistles and ragworts. Misery should be like exotic orchids.”

I do not imagine that the half of an orange facing south would have to tell the other half how warm the sunlight is.

How do I measure Fabienne’s presence in my life—by the years we were together, or by the years we have been apart, her shadow elongating as time goes by, always touching me?

People are oftentimes hideous or tedious. Sometimes they are both. So is the world. We would have no use for myths if the world were neither hideous nor tedious.

“Sad people don’t often know that they are sad and bored.”

“All people are sent to the earth to die,”

The world has no use for who we are and what we know. A story has to be written out. How else do we get our revenge?

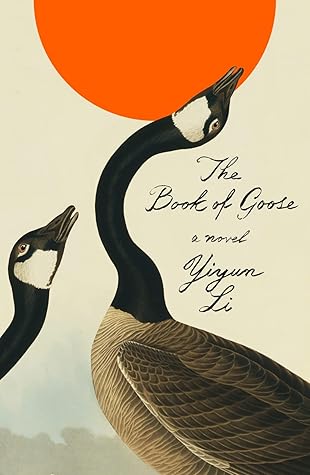

He follows the other geese when they get into mischief, but you can see that his heart is not quite in it. He charges at the postman and terrifies the chickens only because he has to fulfill a goose’s fate. He is, I believe, a philosopher.)

I thought about the inside of my body, the strange shapes with their strange softness, and I could not tell if it was dread or disgust that made me wake up in the middle of night, drenched in sweat. When I could not fall back to sleep, the frogs and the owls took turns to speak some sort of message to me. Sometimes older boys who were already out of school would whistle at me or say something obscene to my face, and then break out laughing. A few years earlier they threw rocks at Fabienne and me, but now they seemed to have lost interest in her.

I lived through her. What was left behind was only my shell.

“But why do you even concern yourself with being dead? We won’t die for a long time.”

the distance between life and death was always shorter than people are willing to understand. One step further, one breath skipped—it does not take much to slip from life into death.

We forgive many people for what they cannot do for us, but not our mothers; we protect our mothers more than we protect others, too. Sometimes I think it may be just as well that I cannot have my own children: I can count more things I would not be able to do for them than what I could; and I would rather march through life without the futile protection from my children. People often forget that it is always a gamble to be a mother; I am not a gambler.

People close to you at one moment may disappear the next moment, but the sky is always there, whether you have a roof over your head or not.

What a tragedy that would have been, living an interchangeable life, looking for interchangeable excitements.

To me, anything that happens is life. A fly dropped dead in the soup is as strange and laughable as a marriage proposal from a mere acquaintance—both happened to me, neither sought by me.

Happiness, I would tell her, is to spend every day without craning one’s neck to look forward to tomorrow, next month, next year, and without holding out one’s hands to stop every day from becoming yesterday.

“It would make the whole world feel like a minefield,” I said. “And I would never be able to take a step.” “No, the opposite,” she said. “It should make you feel that whether you put down your foot here or there doesn’t make a difference. In a minefield a blind person is not more likely to be killed than a person who can see.”

“He makes himself sound more important,” Fabienne said. “Men always do that.”

A year is a year anywhere, a day is a day for everyone, and yet with a few tricks these archivists make others believe that they have packed something into their days, something precious, enviable, everlasting, that is not available to everyone.

Yet in retrospect, with the present to vindicate the past, everyone can claim the illusory status of being a seer.

But don’t count on him. He is a boy and soon he will be a man. Men have very changeable hearts.

Can we say that sunlight moves with wings, and moonlight as if on the back of a snail?

who among you ever questioned why the poor snails bothered to keep their shells, when the shells protected them from nothing?

Days and nights make a week, a month, a life. Drop me into any moment, point me in any direction, and I could retrace my life. Details beget details. With all those details one might hope for the full picture. A full picture of what, though? The more we remember, the less we understand.

Once you get a dead snake, show it to the girls one by one. Let me know which one of them screams and which one asks to touch the body.

The girls, like angels, could look flawlessly beautiful, but that was because no maker of angels needed imagination—some fine material and a set of rules were all that were required. None of the girls would pause in the middle of a conversation about clothes or dances and listen to a faint hooting from a faraway owl; none of them would answer the owl,

That I was to Catalina and the other girls one of the right people, I knew, was conditional. I could have easily slipped back into the opposite category, a nonentity like Meaker.

Couldn’t they see that their words did nothing? Even her flowers, used to all this shouting, carried on their own conversations and slept their own closed-petal sleep.

What was wrong with the muddy muck underneath our feet if we could give it the power to track unseen beings wandering around in the dark? What was a cold tombstone but a door that opened to our own secret, warm chamber?

Our make-beliefs were our allies. How else could we thrive, if not for them: unseen, nameless, patient, always on our side?

Love from those who cannot damage us irreparably often feels insufficient; we may think, rightly or wrongly, that their love does not matter at all.

My life belonged to the dirt, the worms, the manure, the rot underneath.

But I had loved her all my life. I had loved her before we knew what the world was, what love was, and who we ourselves were. But all these things I could not say.

But for all I cared, she could keep her hands there forever, and she could talk about killing me forever. For all I cared, we could spend a lifetime dying in that cemetery.

Being real was like being mad, like thrashing in the most feverish dreams, like being dead while alive, or living on and on after the world considered us dead and buried. But we were too young to die; we were too sane to submit ourselves to madness.

Fabienne pressed her hands hard on my ears. I stayed still, and then heard her shriek, not through the air, but through our bodies. Even with my ears muffled I knew the shriek was terrifying, more animal than human.

“It’s going to be pain and pain and pain and pain from now on, don’t you see it, Agnès?”

people might even think of some nice things to say about me when I’m dead.” Was there no other way for us to get out of this terrible pain?

“Go home, Agnès. There’s nothing we can do for each other now.”

We could not have achieved what those two girls did, letting the world take something from them, letting the world mark them both. And yet from that colossal loss, the loss for which people will always take pity on them, they have earned the right to laugh back at the world, at its people, who cannot understand.

Through her hands I had heard her pain: there was something immense in her, bigger, sharper, more permanent, than the life we lived. She could neither find nor make a world to accommodate that immense being.

Imagination of happiness, after all, is more fragile than most other imaginations.

The real story was beyond our ability to tell: our girlhood, our friendship, our love—all monumental, all inconsequential. The world had no place for two girls like us, though I was slow then, not knowing that Fabienne, slighted, thwarted, even fatally wounded, tried to make a fool of that world, on her and on my behalf. Revenge is a story that often begins with more promises than the ending can offer.

You are still that silly goose, she says. You dream big, Agnès.

If my geese ever dream, they alone know that the world will never be allowed even a glimpse of those dreams, and they alone know the world has no right to judge them. I live like my geese.