More on this book

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 1 - September 10, 2024

I wrote in a place, in a time, in a way that necessarily, but often painfully, altered my fundamental ways of thinking not just about libraries and my time as a librarian but about the world and how I exist in it.

No one is without a voice just because the majority have not been listening.

Although there is no statistic on this, my own experience working within the DC Public Library system showed me time and again that the majority of middle- and upper-class library patrons who wanted to sit and work at a library preferred to visit branches in certain neighborhoods around the District over others, even if it was not their closest neighborhood branch. These same people would comfortably pick up holds from their local branch because it did not require them to linger in the space, but they opted for other libraries if they wanted to stay for longer than a few minutes.

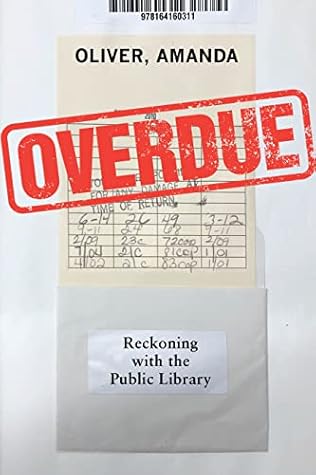

Libraries are resolutely radical institutions. They are free to use and open to the public, spaces that demand nothing from you to enter and nothing for you to stay. No exchange of money occurs between library user and library, save for overdue book fees, which are becoming more and more obsolete.

But to continue to laud libraries and librarians as ever-present equalizers and providers of some version of magic reduces them to something wistfully—and sometimes dangerously—negligible.

What happens when you let an unsatisfactory present go on long enough? It becomes your entire history. —Louise Erdrich

It is often a librarian’s job to make sense of information exactly like this: in pieces, from parts, across decades or centuries, sorted and organized into a collective whole that is, ideally, inclusive and accessible. Or at least to gather reliable resources to help patrons make their own connections.

The earliest free public library in America is generally accepted to be the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1731.

If books were not returned on time, the borrower owed the library twice its original cost, thus creating the first overdue fee system.

White women who had husbands or brothers who were shareholders could borrow as well.

When Franklin and his peers founded the Library Company, teaching an enslaved person how to read was still illegal and punishable by death.

There is also minimal recorded information about the Philadelphia Library Company of Colored Persons, but its founding in 1833 makes it clear that all citizens understood the value of access to libraries and wanted to benefit from them too.

Ticknor, in particular, championed the circulation of popular fiction, a genre that eventually helped draw to public libraries millions of users who had otherwise been disinterested by most early library collections.

The first American public library opened at a schoolhouse on Mason Street in Boston at 9:00 in the morning on March 20, 1854. The library stayed open until 9:30 that night, serving eighty visitors throughout the day. By the end of the year, there were 6,590 registered library users who frequented the library. In 1870 a second branch opened, and the Boston Public Library (BPL) became the first American branch library system.

Death is black in Homer’s Iliad. White signifies virtue, virginity, and innocence in the Book of Revelation.

Light and dark continue to function as deep metaphors, and binary oppositions, for an unending list of sociocultural dividing lines in our contemporary society. And the light mostly wealthy White men envisioned and etched into the foundation of public libraries did not reach everyone, nor was it intended to.

Women from the elite classes volunteered at libraries as well, particularly with children, but it was not until after 1900 that women began to dominate the day-to-day work of libraries.

Library schools were, however, among the first professional curricula to regularly accept female applicants, and an estimated 75 percent of public libraries were brought into existence through Women’s Clubs activism.

In 1896, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC) was formed and began to champion public libraries, bringing books to communities and children who couldn’t access major city libraries.

The Library Bill of Rights was established on June 19, 1939, stating that “a person’s right to use a library should not be denied or abridged because of origin, age, background, or views.”

The funding for many of these early libraries came from Andrew Carnegie, who had first come to the United States from Scotland in 1848 when he was twelve years old.

In his autobiography, Carnegie wrote how he “resolved, if wealth ever came to me, that it should be used to establish free libraries.”8 Between 1883 and 1929, he gave over $60 million of his wealth to fund a system of nearly 1,700 public libraries across the United States.

Carnegie-funded libraries were engraved with an image of a rising sun and similar words as those above the Boston Public Library: LET THERE BE LIGHT. This light, again, did not reach everyone, nor was it intended to.

The light they gave expected that the recipients looked, behaved, and believed in specific ways. It was not meant to shine on everyone, despite what the granite and marble said.

The ALA’s Committee on Work with the Foreign Born published a series of well-meaning guidebooks for adapting collections to meet the needs of immigrants, starting with The Polish Immigrant and His Reading in 1924.

In 1921, Pura Belpré, New York City’s first Puerto Rican librarian, transformed the New York Public Library’s 115th Street branch into a vibrant community center for newly arrived Puerto Rican immigrants by purchasing Spanish-language books, leading bilingual story hours, and offering programs on traditional holidays.

Knowing that Black citizens fared even worse than them, the majority of these immigrants chose to embrace Whiteness and demonstrate their cultural and biological “fitness” to be White citizens, further upholding and protecting the already deeply established White supremacy, segregation, and diminutions of Black citizens.10

In the 1896 case Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court upheld “separate but equal” facilities as constitutional, legally justifying the creation of segregated public spaces for Black Americans.

Between 1908 and 1924, twelve segregated “Colored Carnegie Libraries” opened in smaller buildings, with fewer books and significantly less funding than Carnegie libraries for White people.

Despite Blue’s being a pioneer in the movement to make libraries community anchors, his revolutionary history is often excluded from the story of libraries in America. This is also the case when it comes to the integral contributions of other Black librarians, including Clara Stanton Jones, Virginia Lacy Jones, E. J. Josey, and Albert P. Marshall—all of whom led desegregation efforts and created immense progress in library work overall.

Historians have since noted that if he hadn’t staged the demonstration it would have taken far longer before Black Alexandrians could use a library. Despite his efforts, the Alexandria Library did not become fully desegregated until over twenty years later, in 1962.

On September 15, 1963, two African American ministers, Rev. William B. McClain and Rev. Nimrod Quintus Reynolds, were attacked and severely beaten by a White mob as they attempted to integrate Alabama’s Anniston Public Library on the corner of downtown 10th Street and Wilmer Avenue, a library that was built with the help of matching funds from Andrew Carnegie.

In 1964 Teri Moncure Mojgani, most recently a librarian at Xavier University of Louisiana, participated in a protest at the public library in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. She described the experience in 2018 on a panel titled “Hidden Figures in American Library History” at the main branch of the New Orleans Public Library:

As we see from testimonies like Mojgani’s, the public libraries in the South that did provide limited and inferior services to Black people in the 1950s and ’60s often subjected them to experiences that were humiliating.13

The event came shortly after the ALA passed a 2018 resolution titled Resolution to Honor African Americans Who Fought Library Segregation, or CD#41. The resolution was created to apologize “to African Americans for wrongs committed against them in segregated public libraries.”14

The foundational, and still widely accepted, belief that libraries are freedom-granting institutions for all effectively denies and erases the experiences of hundreds of thousands of Americans across centuries. To uphold and uplift this false narrative also allows public libraries to more easily refuse to create fundamental, deep-rooted change.

In 2017 149,692 librarians in America were White. Only 11,213 were Black, 6,938 were Asian, 4,975 were of two or more races, 1,002 identified as “other,” and 545 were American Indian. As of 2020, 89 percent of librarians in leadership or administration roles identify as White and non-Hispanic.21 With a White majority continually fulfilling roles in libraries and library leadership, other voices are unavoidably lessened, ignored, and lost.

The second is that while public libraries are often lauded as social equalizers and the last bastions of democracy, these affectionate understandings are incomplete in ways that allow for continued harm.

The question of who libraries are for, and who they exclude, should not remain cloaked in half-histories and half-truths. This cover—this shield—is imposed by what I had long thought of as “half-truth histories” before encountering famed American historian John Hingham’s work on consensus history, a term that embodies a pattern of obscuring diversity and conflict in the American past in a smug and self-congratulatory way.

I have returned to my early library memories many times over the years when I need something comforting and easy to hold in my mind, like a soothing balm I can apply to anything, everything.

I could borrow and mine the lives and adventures of others, experiencing life in other centuries, other countries, other worlds. It didn’t matter what I had, or did not have, when I was reading.

The library was not just a place that functioned outside of economic class—it was where I got to choose my own interests outside my brothers’ Star Wars and Indiana Jones that dominated the soundtrack and playtime of our house.

My brothers and I understood the judgment being passed on us. If we were going to be labeled “bad” by others, regardless of how we behaved, we might as well enjoy upholding the label.

Everything from my childhood influenced my decision to become a librarian; I just did not see it at the time. I don’t remember thinking much in high school about what job I might have as an adult, and I hadn’t thought to bring these kinds of questions to my parents. I had been raised to be self-sufficient, and what I could figure out on my own, I figured out on my own. More existential questions like “What do I want out of life and how might I get there?” were ones I asked, but I wasn’t sure how to go about answering them.

It took only one person showing me a graph with the average salary of a librarian to make me decide I wanted to do that. The number, in my memory, was around $38,000. I didn’t quite know what being a librarian meant, but I knew I loved books and liked helping people, and that those were surely essential parts of the job.

How a lifelong feeling of being less-than had left me desperate to please others. It was only once I was a librarian that I began to untangle this internal knot I had created.

Two six-week teaching practicums were required for the school librarian track, and I completed the first at a middle school in the same school district I had attended.

The students were predominantly White, upper middle class, and intimately familiar to me. I knew almost immediately after I started that I did not want to put my skills and energy into working with students who would inevitably have the best possible resources no matter who their librarian was. I petitioned to temporarily move from Buffalo to New York City to complete my second and final required six-week practicum there, and the university approved it.

My supervising librarian, Debbie, was the only negative part of my New York City experience. A former screenwriter and costume designer, she privately called the students assholes and complained to me about nearly every aspect of the job.

It was and is a joke among DC residents that people ask what you “do for work” early on in conversations to see who and what you know and who and what you might be connected to.