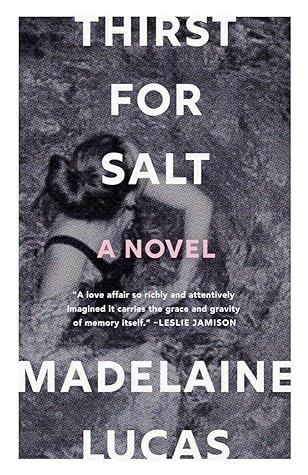

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

maybe what I wanted, what I longed for, lying there with the ocean outlining mine, was to be held in the way you’re supposed to be when you’re no longer a child.

My young face had an openness that tended to reveal too much, and this, I knew, could be strangely intimidating in the way vulnerability sometimes is.

It was one of my earliest memories—my father lifting me from the waves, teaching me which ones to jump over and which to dive under, so I wouldn’t get knocked down. Trusting his arms would be there to pull me up if it got too rough. Those three seconds of tumult, tossed upside down and under, before he yanked me out, calling me his little fish on the line, and held me coughing against his chest. Salt-stung and rashed by sand, but saved. I would never be that young again.

I had no easy way with strangers. Always giving away too much, or saying too little. It seemed clear I had missed some essential lesson.

I wish you could fall in love for the first time again. Or that you’d never loved anybody else before me and neither had I. He laughed and said, Oh, trust me. I was a pretty shitty boyfriend. And anyway, every time is like the first time. That’s the beauty of love. Love erases.

See, the thing is, it seems so romantic at the time—like the most romantic thing you could do—have a baby with someone. To give that to them. But once you do, it kind of eclipses everything. You think you’re ready for it, but you’re not. That kind of love? It’s terrifying.

Maybe to be a lighthouse keeper’s daughter is to live a reckless, freewheeling life. Dwelling on the threshold between abandon and abandonment, perched above the ocean’s violence, a father’s job to light the way for those traveling through the dark, not yours.

In a world without boundaries, I could lose myself.

It felt good that he needed me for something, that there were things I had over him too—like my twenty-twenty vision, and time. Although time, as Jude liked to say, time is on nobody’s side.

I searched his palms, trying to tell our future, but they only told stories about his past.

She always said I had my father’s hands, and there was a time I collected these things she told me, as if to remember—like proof—that he was a part of me too. Because when I looked in the mirror I couldn’t see it,

When I was a child, I used to make up extraordinary stories about my father’s absence. My father was a captain and he died at sea.

We had waited a long time, my mother and I, for my father to get his life together. As we moved in and out of motels, houses, we tracked him—from Broken Hill to Adelaide, down near the Bight and across the Nullarbor—while he went searching for better luck or money.

When I turned eighteen, I stopped trying to track him down. I was on my way to university, eager to leave the sadness of childhood behind, and I had the sense that these visits were too much for my father too. So, in the way of lonely people, we let each other go. In the last note he wrote me, postmarked Coober Pedy, he said with resignation that he had expected this day would come. No fight left in my father, then. You’ve always been your mother’s daughter, it read.

There was a power in walking down the street with him, the way he carried himself like the world’s beloved son, whereas I had always felt like its illegitimate daughter.

I was surprised by the realization that even if he was not reliable in the way that I’d imagined, I did not desire him any less.

And if I was essential, the other half of whatever he was, then he could never abandon me.

Married years are like dog years, my mother was fond of saying. They count for more.

But for the first time it was becoming obvious to me that there was no one way to live your life. Each of us had to make her own choices, and in that we were all on our own.

You always did like a man you could climb, like a ladder, like a tree, she said to me slyly in the kitchen, while I was making tea and Jude was in the bathroom. Not me, she said. Give me a lover I can look in the eye. Don’t want someone always looking over me, looking ahead, looking out for someone new.

Unrequited love is still love, he said. But it’s never a great love. Can’t be. It’s one-sided. Except in the case of the ocean. For the ocean, we can make an exception.

Isn’t it strange to see lightning with no thunder? When I was little, my mother told me this story so I wouldn’t be afraid. She said it was just angels taking photographs of all the little people down on earth, so they’d know what it was like to be human. The lightning was their cameras flashing. It meant we must be doing something special. And why would the angels want a picture of us two? Because we’re lovers, I said. And they can’t imagine what it means to be lovers.

Sometimes I think you must have seen it all before. That I can’t show you anything new. You show me things I’ve forgotten, he said. Which is almost the same. Maybe even better. And anyway, don’t forget I was young once too.

I can see it all over your face, he said. Such naked wanting. I told him that I’d always been afraid of wanting anything so badly that it becomes visible. For years I’d tried to compress my desires, to burn them away, like waste. I had this theory, I said, that that was why I would never be graceful. My body jarred from the fight of trying to keep it all inside me, it made me clumsy. Desires would rise up and I’d knock an elbow into something, or my hand would give out on the glass I was holding and I would watch it as it slipped through my fingers, shattered. I hoped so badly, I told him, to

...more

I had so few real responsibilities at that point in my life and yet I was ready to abandon all of them. Forgetting, back then, that I still had to eat, to pay rent, that a world existed outside his bedroom door and that there might come a time when once again I had to live in it. I could not survive on love alone. Forgetting, most of all, that we had been together only four months and we were delicate and untested.

Memory’s funny like that—the way it distorts distance.

He called me Love, as if it were my name. As if I could be the very thing itself.

I think now that this is something that happens in small families—roles get confused, relationships do double duty. So a daughter might play the part of an overprotective parent, or a mother might rely on the daughter like a partner. Mother as runaway child, daughter as mother, daughter as husband.

Do you love me? Do you love me? I asked, shaking him awake in the dark. His rotation of answers: You know I do. Don’t make me say it all the time or it will lose its meaning. If I didn’t, would I still be here, in bed with you?

I wanted us to be like rocks or anchors, keeping each other in place.

Love, I’d read, was supposed to be a light and weightless feeling, but I had always longed for gravity.