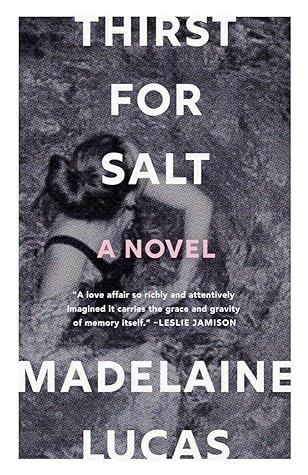

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Where I come from, she’d told me on our first day of university, when I sat next to her in the lecture hall for orientation, teenagers move to the city or else they tend to die. Which was eerie, coming from Bonnie, with her round angel’s face and soft way of speaking, her pale brows and hair so blonde it was almost white. This contrast had surprised me, and I liked her immediately. Bonnie had the kind of practical experience I lacked, and I hoped that she could teach me—how to dress, how to wear my clothes. How to be the sort of woman I aspired to be.

I am my mother’s daughter. It was her face, blinking back at me in surprise. Something wild about us, our frayed edges.

But for the first time it was becoming obvious to me that there was no one way to live your life. Each of us had to make her own choices, and in that we were all on our own.

They couldn’t know then how much things would continue to change in the coming months. Neither could I. That we should have held on to the sweetness of those days, the three of us, making coffee, talking, idling away hours because we had nowhere to be. We were home.

I would learn that things I perceived as abandonment were Jude’s acts of trust, like the way he always walked ahead without looking behind him, trusting me to keep pace, to follow. But I was the kind who always looked back, glancing over my shoulder whenever I turned a corner, as if I were a woman descended from the line of Lot’s wife in the old parable.

At my place, Jude was unsure where to sit or what to do without work to tinker with or records to turn, fish to salt, birds to feed. Something about him was never quite at ease there. In our house of girls’ things, he was like a man trying to shrink to fit inside a dollhouse.

I want to do everything right this time, he said. His strange mood from the night before had passed. And although I’d never been in a serious relationship, I felt like I knew how to do this too. Yes, I nodded. I’d been waiting my whole life to love and be loved like that.

We always brought the beach home with us, stumbling barefoot up the path that cut through the bush to his yard.

Down south, there was always the feeling of water in the air, even when there was no rain.

I was so eager to be loved by him, to be held in his arms and reassured, to shut out the ghosts of other girlfriends from the room like a cold draft,

I can see it all over your face, he said. Such naked wanting. I told him that I’d always been afraid of wanting anything so badly that it becomes visible. For years I’d tried to compress my desires, to burn them away, like waste. I had this theory, I said, that that was why I would never be graceful. My body jarred from the fight of trying to keep it all inside me, it made me clumsy. Desires would rise up and I’d knock an elbow into something, or my hand would give out on the glass I was holding and I would watch it as it slipped through my fingers, shattered. I hoped so badly, I told him, to

...more

Bordered by the bush on one side, the bay on the other. We had grown up in cities and to the locals that meant strangers, other men’s women.

I felt his love then like a rope around my waist. If I strayed too far, it seemed, or went out too deep, he’d pull me back, a tether to the known world. I felt both limited and also comforted by this. It was a new feeling.

I’d read in a report in the local paper, this town could be underwater. I remembered it because of the unusually poetic language in the headline. With predicted rising sea levels over the next century, Sailors Beach could slip beneath the waves. How it sounded almost like a relief—to surrender like that. Back then, I often confused danger with beauty, drawn as I was to stories of other people’s tragedies, tales of lighthouse keepers’ daughters, lonely men and women living out on the edge, perched above those same wrecking waters.

Small wounds reopened, paper cuts never seemed to heal.

I’d wrap myself around his legs the way I used to hang from my father’s when I was a child and he would come to visit—remembering the way he used to play along, swinging me from his boot with each heavy stride.

Love, I’d read, was supposed to be a light and weightless feeling, but I had always longed for gravity.

What I longed for was a guarantee that if this love ever ended, at least there’d be a record of it, outside of the two of us and our two bodies. Though part of me knew, of course, that it could never work like that—what a burden to put on a child.

I do miss you, I thought, though he was right there with me, standing in the morning light, and I was holding him.

The flowers had seemed like a promise that a different life was destined for us. Glamour, my mother knew, could be another temporary cure.

It seems now that we have always been drifters, my mother, my father, and I. We swayed, touching others only lightly, ebbing closer and away with the loose tide.

In the country, my mother told me, my grandmother had developed a reputation—a single woman, the only divorcée for miles, and unafraid of blood, known for delivering horses on her property.

I was superstitious in those early days up north. Counting and recounting the days of the month on my fingers. Lying on my mother’s couch reading Play It as It Lays with the curtains drawn against the heat, dressing all in white, like Maria.

THERE MUST BE PEOPLE out there who are not drawn to the shadow of what could have been, who feel no pull toward the other lives they could be living, but I certainly have never been one of them.

A way of trying on a life we weren’t quite ready to inhabit ourselves. All along we’d danced on the edge of it—by the side of the highway with the windows rolled down, on the beach with the sand beneath us sounding like a violin being bowed at high pitch, out in the yard with the birds.

Women are born with all their eggs in their ovaries, like the seeds of a fruit. I’d been with my mother since she’d been in my grandmother’s womb, and now I was sleeping in her bed and my mother was in the next room sleeping in her mother’s. It made me think of us like Russian dolls. Women carried inside women carried inside women.

I didn’t belong to elegance, but like my mother, I was calmed by the presence of it. It seemed to suggest somebody was in control.

As all lovers learn, when love ends, you lose the future as well as the past.

My body like an hourglass, moving time in blood instead of sand.

A MAN STRIKES A MATCH and starts a fire in the house of love. A woman takes a pill to make herself bleed.

What continues to surprise me, and what I still don’t understand, is not the reasons that love ends but the way that it endures.