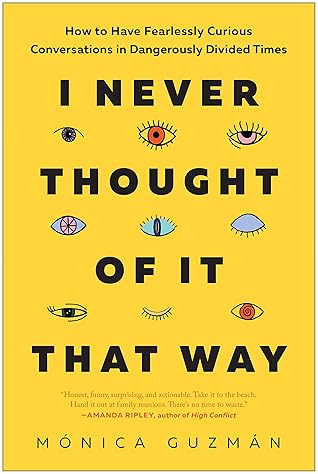

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Started reading

October 17, 2022

False stories soar because good people relate to something in them that’s true: a fear or value or concern that’s going unheard, unexplored, and unacknowledged. Every time? Yes, every time! Why do we ignore that?

how we sink, over time, into a hole where our attitudes are reinforced instead of challenged, particularly about what those other people think.

A call for help. They’re blinding us to each other’s perspectives, turning our neighbors, friends, and relatives into fools and monsters, and cranking up the volume way too high on what is already a cacophony of information that drowns out so much else.

when we surround ourselves with similar people, we get the benefit of facing fewer moments where we reckon with our judgment of other people’s decisions—or their judgment of ours.

The more things that get involved in each election, the more vulnerable our self-esteem is.

That’s what happens when you’re surrounded by people who share your gut instincts: You end up sharing your blind spots, too. And when the whole group has the same blind spots? You’ll amp up each other’s ignorance and make bad decisions even more spectacularly together than each of you would have apart.

Sorting is the complex, almost invisible process by which we end up close to people who are like us. When we push off from people who are not like us in some way that matters, disparaging them as a result, that’s “othering.”

But here’s the thing: Too often, othering makes monsters of good people.

No us can see a them clearly. And the more we vilify them, the more distorted the world between us becomes.

The boys set out to judge reality and ended up seeing their group’s superiority—sometimes, with a little flair.

To sum up their findings: When we look at the other side, we don’t see reality. We see an exaggerated fiction that distorts people’s actual beliefs. When this Perception Gap study was released in 2019, it found that, on average, Democrats are off by 19 percentage points when estimating Republicans’ views, and Republicans are off by 27 percentage points when estimating Democrats’ views.

Researchers who study political division talk about three kinds of polarization. The first is ideological polarization, due to actual policy disagreements between people. The second is affective polarization, due to growing animosity between people in either party. And the third is “perceived” or “false” polarization, the “degree to which partisans overestimate the ideological division between their side and their opponents.” Ideological polarization is based on reason. Affective polarization is based on feelings. But false polarization? That’s just based on a lie.

She brought up what Don Lemon had said back in October, and how two days later, her sister had unfriended her on Facebook. “I kinda think that he gave the approval,” she says, “that it’s OK to give up on people that you love.”

This... just... so much of this. Yes, there are times when our family members are *truly* toxic and cutting ties with them is necessary... but it's like this trend of cutting people out got so popular that people started doing it over the smallest things. And that just crushes my heart.

And finally, when people around you agree with you, you get more confident that whatever you stand for is the right thing to believe. You’re getting validation. It feels good, and it builds momentum. So it’s just a matter of time, really, before you take another rhetorical step in the direction you’re already leaning.

Here’s my point: Your silos are not neutral pits of preferred information. Online, they are structured by platforms that want you to consume that information as long as possible.

We get our news increasingly from within our silos, from the voices and spaces that make up our preferred sources of information. And the more time we spend on the news, it turns out, the more distorted our view of the other side becomes.

Siloing goes too far when the stories we tell about each other are not only wrong but demeaning. When we spend so much time in spaces that intensify our basest judgments that we believe the other side is barely human at all.

Then powell goes on, making a distinction between building what he calls short bridges and long bridges that I find handy as heck. “Build short bridges and become more practiced, become more skilled at building bridges,” he says. “And then, at some point, you may need to re-question, ‘Who are you calling the devil?’”

But when liberal and conservative judges worked together, that dampened their ideological tendencies. In both cases, what made the difference wasn’t exposure to information or education, but people.

What happens in the world matters, but our interpretation of what happens in the world matters more.

It’s weird to do anything drastic when you can barely make out the thing that’s scaring you. So you’ll do something to resolve that: You’ll manufacture certainty. You’ll convince yourself that the shape you see beyond your ken fits the description of that sea monster everyone in your silo’s been buzzing about. And you’ll fight, flee, or rage accordingly.

then turn away from each other. Let’s do our own exploring, too. Let’s put our perspective next to someone else’s with no middleman, meaningfully and frequently enough that what we observe becomes a check on what everyone’s going on about.

That’s what I call the signal: an “I never thought of it that way” moment, or an INTOIT moment.* That phrase describes something amazing. Catch yourself thinking or saying it, and it’s the clearest sign you get that a new insight has spanned the distance between someone else’s perspective and your own.

A promise that one way or another, no matter how tempting it would be to dismiss and vilify and even hate whoever didn’t see things the way I knew them to be, that I would do everything in my power to remain stupidly, insistently, ferociously curious.

Most of the time, complexity ain’t sexy. We’re too busy or tired for it. Prone to reaction, not reflection.

The reason why is simple: If you think you know, you won’t think to ask. The voices in your silos have all the answers anyway. Easy answers that surround you, that jibe with your perspective, that promise that this or that issue “really just comes down to this

He talks about how healthy it is for our minds to see different things and check out different customs. Not just so we can know, like, how many steps are in the old Pantheon in Rome, he says. But also to “rub and polish our brains against those of others.”

And when a bridging conversation succeeds in leaving room for our questions, it addresses our tensions, too, which levels everything up by making it easier to get curious. Why? Because rejecting easy answers to explore more complicated ones isn’t so hard when it isn’t so stressful.

When there’s more trust, there’s less fear, and taking risks in bridging conversations becomes easier. The bonds we make in conversation help us talk about harder things.

Litman calls the parched type “deprivation-based curiosity,” or “D-curiosity,” and the mouth-watering type “interest-based curiosity,” or “I-curiosity.”

We don’t want to burden ourselves with conversations that stress us out or scare us. On the other hand, we can’t just avoid each other all the time, or treat every exchange with someone who doesn’t see things our way like some high-stakes showdown. All that just blinds us, reducing our world to whatever’s contained in the solid walls of our silos. So as we start to reach, we need to find some purchase with each other’s perspectives. We need to get a grip.

You can tell you’ve built up the traction a bridging conversation craves when people get comfortable with the uncomfortable.

Good listening is not silent waiting.

To build traction, you have to not just listen, but listen for the meaning people are trying to share with you, the signals they send about where the adventure could go next.

Sometimes you have to step back from a conversation for a moment to check and see if something is making traction slip. Only then can you try to fix it.

But before we can listen for meaning, observe how it’s received, offer our story, or pull on information that fills gaps in our knowledge, we often get stuck protecting our perspective or attacking another person for theirs. And that’s because of our tendency to do something that blocks our view of people altogether—assume.

Despite all my supposed bridge-building cred, I realized right then that I’d come into this trip believing that it was people in rural areas who had more to learn from people in the city than the other way around. What a strange, self-serving assumption. It was an instant INTOIT moment for me, and—by the slow nods and murmurs I heard around me—a few others. Who do we think we are? Who do we think they are? How are we so sure?

That detail was an INTOIT moment for Laura Caspi. Learning about that policy and other details she heard about people’s lives here checked two of her biggest assumptions. The first was the idea that any vote for Trump must be a vote against the things that drove her own vote. “It didn’t enter my consciousness that they voted that way for reasons I hadn’t even considered, or for reasons that didn’t matter to me,” she said. “Our lives are so different . . . We’re not even playing the same game at the end of the day.”

If in one short interaction you find reason to question the assumptions you’ve received from your silos, what other assumptions in your life are you totally wrong about?

How did she think past the stereotype? Because she had a friend who worked as a construction manager. It demonstrated a truth about our assumptions: they are only as good as our experiences.

All we can do is notice the assumptions we’re making and ask why. Fail to notice your assumptions and they might harden into lies. Turn them into questions and they’ll get you closer to truth.

We think of perspectives as interpretations of information. But when it comes to the things that divide us, perspectives are information. And gathering more perspectives gets us closer to a bigger, more complicated truth. You won’t resolve the debate over abortion by listening closely to a woman who believes abortion murders human beings and another who believes abortion grants women the freedom to live full and free lives. But you will get a clearer picture of what’s at stake for different people, and why the issue is so challenging in the first place.

One way we get stuck on reason is when we insist on our own perspectives to each other instead of letting them inform and enrich one other. That’s not conversation but competition, and no one wins.

when we insist on our own perspective, we leave no room for others, believing that the framework we put around things is the only valid one there is.

So if you think the other side is devoid of logic, “facts,” or good faith argument, you might be right: some beliefs are just plain deviant and some believers are just plain trolls. But it’s far, far more likely, I’ve found, that you’re buried a little too deep in your silo to see why their arguments, from their perspective, do at least make sense.