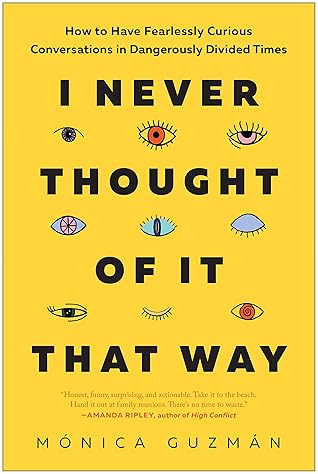

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

July 2 - August 1, 2025

Who would feel at home in our country tomorrow?

I realized what for years I’d been too petrified to notice: everybody’s so inexhaustibly interesting.

I began to see political polarization as the problem that eats other problems, the monster who convinces us that the monsters are us.

False stories soar because good people relate to something in them that’s true: a fear or value or concern that’s going unheard, unexplored, and unacknowledged. Every time? Yes, every time! Why do we ignore that?

Misinformation isn’t the product of a culture that doesn’t value truth. It’s the product of a culture in which we’ve grown too afraid to turn to each other and hear it.

Curiosity is big and it is badass. At its weakest, it keeps our minds open so they don’t shrink. At its strongest, it whips us into a frenzy of unstoppable learning.

We see people by peering behind their views to the paths they walked to get to them.

One reason we’re dangerously divided is because when so many of the identities and preferences that matter to us line up with our politics, it changes how we feel our politics.

The platforms use the “birds of a feather” phenomenon to keep our attention as long as possible. They rely on our love of sameness (and our suspicion of others . . . more on that later) to predict what we want based on who we are. And every post we like, group we join, and profile feature we edit help them recommend more voices like the ones we already follow, more groups like the ones we’re already in.

That’s what happens when you’re surrounded by people who share your gut instincts: You end up sharing your blind spots, too. And when the whole group has the same blind spots? You’ll amp up each other’s ignorance and make bad decisions even more spectacularly together than each of you would have apart.

“To know what has come before is to be armed against despair,” historian and presidential biographer Jon Meacham wrote in The Soul of America.

No us can see a them clearly. And the more we vilify them, the more distorted the world between us becomes.

When this Perception Gap study was released in 2019, it found that, on average, Democrats are off by 19 percentage points when estimating Republicans’ views, and Republicans are off by 27 percentage points when estimating Democrats’ views.

In a 2018 study that made my jaw hit the floor, Americans thought that a third of Democrats were gay, lesbian, or bisexual when just 6 percent are, and that four out of ten Republicans earn more than $250,000 in a year (that’s a quarter-million dollars, folks!) when only 2 percent actually do.

What’s underrepresented in your communities will be underrepresented in your life and overrepresented in your imagination. It’s harder to interact generously with people who hold perspectives that concern you, so it’ll be way easier to other them.

I’d created a custom world to serve my every need. How could the world around me possibly compete with it?

“Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention, and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.”

But when liberal and conservative judges worked together, that dampened their ideological tendencies. In both cases, what made the difference wasn’t exposure to information or education, but people.

We don’t see with our eyes, after all, but with our whole biographies. It’s time our sense of perspective took that into account.

Only some people have the time and resources to research, theorize, communicate, promote. So someone is better at writing; are they better at living? Let’s kill that idea once and for all. You, me, each of us has expertise as unique as our paths through the world—a ken built over a lifetime as undeniable as any other. The story of the world feels like it’s the experts’ to tell. It’s not. It’s all of ours.

“Anyone who isn’t confused doesn’t really understand the situation.”

In a lot of ways, confusion is just complexity before you put curiosity to work.

because this idea that our brains need polish and that the polish is other brains . . . Merci beaucoup, Michel. You nailed it.

When we’re in conversation, we’re somewhere we’ve never been before. We’re meeting particular minds in particular states at some particular moment. You had to be there because there’s nowhere else like it in the world.

Listening, the way I see it, is about showing people they matter. To build traction, you have to not just listen, but listen for the meaning people are trying to share with you, the signals they send about where the adventure could go next.

People aren’t puzzles; they’re mysteries. What’s the difference? “Puzzles are orderly. They have a beginning and an end. Once the missing information is found, they’re not a puzzle anymore,” Leslie writes. “Mysteries are murkier, less neat. Progress can be made toward them by gathering knowledge and identifying the most important factors, but they don’t offer the satisfaction of definite solutions.”

If we don’t choose our opinions, why do we spend so much time trying to talk each other out of them? How savagely should we judge each other by them? If our beliefs form naturally over the course of our lives, is it the course of our lives, rather than a battle of reasons, that best explains our opinions to others?

“Which do you value more: the truth or your own beliefs?

What would it take, then, to help people share their opinions in an adaptive, nuanced, conversable world, rather than one where their opinions will be taken as proxies for who they are?

We shouldn’t focus on understanding, rather than winning, just because it’s smarter. It’s also the only approach that values other people as people by giving them the space to be who they are. You can’t get traction with a mind you’re trying to defeat. Uncertainty that searches for truth gets there faster than certainty that asserts it. “We are more intimately bound to one another by our kindred doubts,” wrote Seattle-based essayist Charles D’Ambrosio, “than our brave conclusions.”

we treat our opinions as proxies for who we and others are—overguarding and overjudging accordingly.

“The shortest distance between two people,” said the celebrated Chicago Black youth advocate and entrepreneur Darius Ballinger, “is a story.”

There aren’t an infinite number of human values out there. There are only ten: stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, benevolence, universalism, security, conformity, tradition, and self-direction.

ask for people’s concerns, and they’ll show you what they value.

Listening is about showing people they matter.

When you show people that you want to get their meaning right, you’re listening at a level they’re not used to. That will not only fuel your curiosity but supercharge the conversation’s ability to form a bond between everyone in it.

We don’t see with our eyes but our whole biographies. The fact that we can transmit even a fraction of that meaning to someone else with language is a marvel.

“Live life in the form of a question.”

here are four characteristics I’ve learned make for not only better questions, but much more fulfilling conversations. I call it the CARE check: if your question is curious, answerable, raw, and exploring, you’re on the right track.

“Honesty, curiosity, respect.”

Take one step closer to someone who disagrees with you—whether that means spending time with a friend or relative you’ve been drifting apart from, reading an opinion from an earnest voice on the other side, or sparking a conversation you’ve been both eager and hesitant to have.

When you want to explore why they’re wrong, explore what you’re missing. When you want to determine whose view wins, determine what makes each view understandable. When you want to discover why someone believes something that confounds you, discover how they came to believe it.