More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

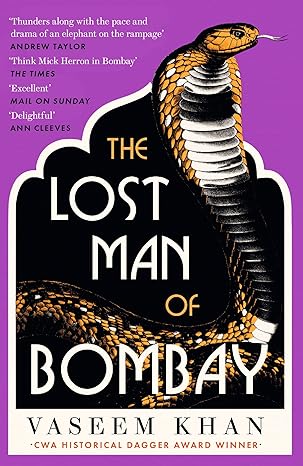

Vaseem Khan

Read between

November 10, 2022 - January 3, 2023

Since the numinous hour of independence, many of the revolution’s earnest ideals had fallen by the wayside. Nehru had inaugurated the new nation in an ecstasy of sanctimony, but the backdrop of Partition and the riots that had left a million dead was proving a poor platform from which to set out a mantra of unity and universal brotherhood.

The new India often seemed a country where not only were few singing from the same song sheet, but where the song sheet had been torn to shreds, and the pieces set alight, along with the song’s composer.

In the monsoon, the open sewer became an excremental horror, the tide seeping through invisible openings and washing over the flagstones.

As Parsees, she and Sam were members of Bombay’s smallest religious community, their faith tenuous since her mother’s passing. The only thing she could say for sure was that her mortal remains would be fought over by the vultures that flocked to Bombay’s Towers of Silence.

The banking sector had been transformed in recent decades, primarily by the swadeshi movement – the call for self-rule and self-reliance – a banner taken up by Gandhi during the Quit India years. Private banks run by Indians for Indians had mushroomed around the country, loosening the stranglehold of the Imperial Bank of India, bastard love child of the British-chartered presidency banks of Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras.

He stared at her with undisguised loathing, his hatred a tangible thing, squirting from him in pungent whiffs as he turned and walked stiffly away.

She had enough self-awareness to acknowledge that the English-man’s lack of savoir-faire was matched only by her own. The difference was that Blackfinch, bewilderingly, rarely seemed to cause upset. Indeed, he was positively well liked. His awkwardness and innate ability to say the wrong thing at the wrong time only seemed to endear him to others, whereas her own forthright manner had left her alienated and mistrusted.

It was only later, when the independence struggle had dug its way under her skin, that the inherent perversity of the club’s refusal to entertain the people of the country in which it stood became obvious to her. She remembered Aziz eloquently explaining for her the British mentality. ‘Did you ever read Robinson Crusoe? The British still in India are very much like our shipwrecked mariner. They find themselves marooned in a land of bounty, but a bounty that can only be harvested through great trial and tribulation. It’s a shock to them when they discover that the natives – we poor Man Fridays

...more

His handsome face, his perennial expression of mild bewilderment, the sense he always gave her of being hastily assembled by a god with other things on his mind.

He’d spent the remainder of his life practising ahimsa, the Hindu concept of non-violence, and extolling his own virtue via a succession of edicts inscribed on stone pillars, many still dotted around the subcontinent.

The shop’s familiar beige walls had been transformed by a medley of bright colours: white, peach, and umber. The overall effect was of a mosaic, or the contents of a volatile stomach.

From the wall a portrait of George VI looked down at her with gormless benevolence.

She found a Tibetan hole-in-the-wall restaurant, an oasis in the midst of the mercantile bedlam, and ate a plate of momos with a glass of lemonade.

‘The man who set up this institution was an Englishman. A few miles from here is the Survey of India. Its most famous Surveyor General was also an Englishman, a military man by the name of Colonel Sir George Everest. He lives on now with the mountain that bears his name.’ Batra leaned forward. ‘Yet Sir George never set foot on Everest, nor did he have anything to do with determining that it was the world’s highest peak. That calculation was carried out by an Indian named Radhanath Sikdar. History, alas, named no mountains after him . . . I think it’s high time we stopped worrying about

...more

That had been Gandhi’s great achievement. To demonstrate to the world that you couldn’t claim to be the arbiters of fair play while cheating your fellow man at every turn.

Yet, it wasn’t her fault. Perhaps if she repeated that enough times, it would become the truth, or at least a lie she could live with.

Stalin had once mused as to how so few Britishers had managed to rule a country of three hundred million. The answer was not in force of arms or even the machinations of divide et impera. It was the dead hand clutched at the throat of every native via the Indian Civil Service that had brought the country to heel. With forms required in triplicate for matters as simple as recording the death of a water buffalo, was it any wonder that generations of bewildered Indians had found themselves entrapped by the so-called steel frame underpinning Britain’s colonial enterprise?

Remember, the bulk of British revenue was generated through taxation, primarily land revenues. But anything that could be taxed was taxed. Given the chance, the British would have taxed the last breath out of a donkey.’

Whatever he’d achieved, he’d achieved off his own back. But he told me they’d never let him go higher than Additional Collector, always answerable to some inbred fool from the Home Counties a decade his junior. It left him with a chip on his shoulder the size of Wales.’

Though barely eight thousand square kilometres in size, the state had enjoyed a long history of relative prosperity, inevitably attracting the interest of the East India Company. A short-lived rebellion in the mid-nineteenth century had been brutally put down, and a docile regent installed, handled by a political agent at court whose ruthlessness had been matched only by his avarice.

The avarice of men with nothing to lose. Sometimes, I wonder what we might have built had the British chosen to treat us as equals instead of inferiors, as a nation to be developed, instead of merely plundered. The great civilising mission they spoke about was a comforting lie, a tale to help them sleep better at night. They came here for bounty, and when they left, they were like schoolboys fleeing a ransacked sweetshop, pockets loaded down with all they could carry.’

‘None of us are entitled to a long life or even a good one,’ he’d told her. ‘Make the most of every moment.’