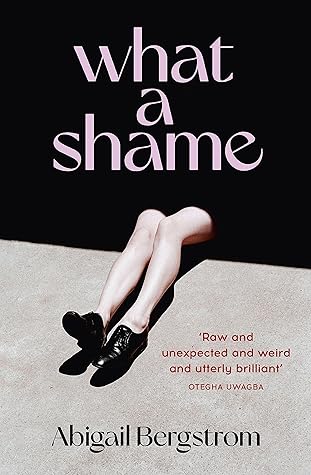

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Now that you’re both gone I’m struggling to decipher which thread of grief belongs to each of you. It’s a wiry tangled mass in my chest, like those metal scourers you use to scrub stubborn pans. Each coarse steel strand is more tightly coiled than the last, and when amassed tightly in your hand it’s soft to touch. Only when a single strand frays loose is it sharp and painful; I think that’s why it’s easier to keep you both matted together.

Because pain gets us all in the end, doesn’t it? We all must suffer eventually. The only question is: when?

You know what to do with the anguish that immediately seeps from an ending – sudden or slow: you have been taught. It’s the ongoing and ebbing sadness that continues afterwards that we all find a little dull.

There’s only so long those who love you can dampen their own happiness out of sensitivity for your misfortunes.

Why would you go back there?’ ‘Because when someone makes you feel like you’re not good enough for them you become completely consumed by the task of disproving their theory.

‘Do you not think that some of us are just too fucked up? People settle down and find each other, like you and Henry. Or they don’t, and what’s left are the broken people.’

But in this story, as in real life, we don’t end up with our Mr Bigs or our Mr Darcys. It’s a cruel trick that’s been played on women. Repeatedly promised that therein lies our happy ending, we follow an ill-written script.

resent that comment. It’s easy to say, ‘Let it go, Mathilda. Move on,’ but the reality is much harder to execute.

That which we do not bring into consciousness appears in our lives as fate. That’s what Jung wrote. Meaning that which I do not allow myself to process I then create out of all that’s around me.’

He said shame was interesting because it was the place where the self and society cross.

‘Do you know what keeps us so contained, ladies? Do you? It’s shame. Your shame and my shame. It keeps us tempered. We perform a role – a lot of us learn that performance from our mothers.’

You. Yes, you. We’ve had enough of you. We will no longer tolerate you. You, who break us like we’re china dolls. You, who hurt us. You, who make us afraid when we’re alone with you in cabs or outnumbered by you on buses. You, who impose yourself on us. You, who fuck us without our consent. You, who push our legs back. You, who rape, pillage and maim us. You, who pin us up on billboards and in magazines to show us we’re not good enough. You, who shroud us in pain and violence in porn. You, who steal our education from us. You, who tell us we cannot vote. You, who tell us we aren’t women

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

But the word ‘rape’ felt so loaded. It belonged to women worse off than me, to women who experienced violence and pain, to women with bloodied thighs who were attacked by strangers in dark alleys or coerced by obnoxious bosses at work.

Sometimes it’s mutual trauma that draws us to our lovers. The scars on our hearts draw out the same patterns.

It’s romantic that the lovers are frozen in time – why? So they never start to look haggard? So we never have to see them get sick of one another, tire of each other or grow resentful of the compromise demanded in a real relationship. We don’t have to see the love come to an end, which it will because all things have a beginning and an end. So smash the vase.’

‘Kintsugi is the art form of repairing broken ceramics with a gold lacquer. It fills the gaps and makes what’s broken central to an object’s design, visible for all to see.’

Imperfection and broken pieces can define beauty. It became what it is because it was broken. Through its repair it is defined.’

‘That’s all we’re made up of,’ Constance takes a deep breath. ‘We’re just energy. And there’s good energy and bad energy, and it’s something we recognise in one another. Sometimes we’re drawn to a person and we can’t explain why. We

Did you know that after death a human body weighs twenty-one grams less? Some people believe that is the weight of a human soul. Others think it’s down to a rise in temperature when the lungs stop receiving oxygen and cooling our blood, which results in excess sweating. Either way, energy can’t be destroyed, so arguably when we die it must go somewhere.’

You think the best part of your life has happened to you. But life isn’t like that. There are better things to come, happier times.

‘It’s hard to decipher what has sentimental value and what doesn’t after spending that much of your life with someone. At first, everything is a piece of them – there isn’t a pair of trousers that doesn’t remind you of a trip you took together or of a silly thing they did. But that fades, I suppose, and you realise they’re just things, things that couldn’t begin to capture the magnitude of that person and all you loved about them.’

Trick question! A person is neither good nor bad, rather an amalgam of both. But it’s difficult to accept those two opposing concepts at once, to let them sit together in unnerving proximity.

‘A patchwork quilt of grief stitched together by how much we love each person we lose – something to wrap around us in the lonely nights.’

Grief is a good thing. It means that you loved someone. It means that they mattered.

‘No one is ever fine,’ Georgia says. ‘That’s just something people say. People are very rarely just fine, so stop saying that all the time.’