More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

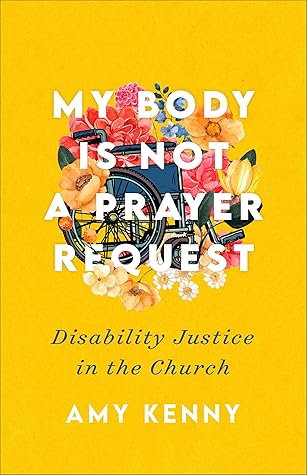

Amy Kenny

Read between

July 1 - July 13, 2024

“I’ll prove them wrong,” I steadied myself, revenge music blaring in the background. Every snide remark about disability only added fuel to the fire of my determination. I believed I could change my educators’ minds because I had right on my side. I thought that if I was smart enough, hardworking enough, and achieved enough, I could make them value disabled people. I thought that I could perfectionist my way out of disability discrimination.

Imagine if instead of trying to pray away my body, Christian communities invested in making sure they didn’t bankrupt me. Imagine if churches ensured that no disabled person in their community paid the crip tax alone. Imagine if we were invested in one another’s thriving enough to pick up the bill.

When we approach life with a healing mindset instead of a curing mindset, we invest in the flourishing of our neighbors and open ourselves up to all kinds of possibilities that we never thought possible. My story, my disability, my healing has a ripple effect in the community. It is not just my body that benefits from the knowledge of healing; it is good news for the whole community. It allows others to reimagine what flourishing can be.

It’s not solely about language, either. The problem with centering his emotions is that doing so means refusing to take responsibility for how words scorch marginalized groups and instead uses the dictionary and the Bible to justify the burn.

To use my body as a symbol, to equate my body to something embarrassing or undesirable, produces an emotional link at the expense of my experience. Using disability as a metaphor “others” disabled people. Blind, deaf, mute, lame, crippled, dumb are all frequent metaphors predicated on the idea that the bodies and minds of one-quarter of the US population are unwelcome or unworthy.

Yes, even disabled people secretly yearn to be “normal” on days when it feels like our bodies let us down. We have so internalized the expectation that our bodies should function in a linear way that we can feel frustrated when they don’t play along.

The hardest part of being disabled isn’t the pain, it’s the people. It’s trying to explain. It’s asking people to rethink all their assumptions in text messages. It’s being bombarded with slurs about me every day that no one seems to think are a big deal. It’s getting up the courage to share my pain with someone, only for it to be dismissed by comparison. (No, my disability is not like that time you broke your ankle in junior high.) It’s having to weigh the pros and cons of sharing any of this with someone, risking the relationship, knowing they might roll their eyes at my frustration. Or,

...more

Bodies are like gardens. We can put the right ingredients in the soil. We can tend to them and cultivate growth in various ways. But the ultimate success of the crop isn’t up to us. It is dependent on the temperature, water, humidity, and sunlight, all of which are out of our control. Our damaged organs or limbs cannot be replaced like a snapped fan belt. Sometimes we do all the “right” things—eat nourishing foods, exercise, reduce stress—and yet there are parts of our bodies that are not normative.

God doesn’t see me as disabled, yet communities gathered in God’s name disable me from fully participating. When a group of nondisabled people make all the decisions for a community, they unwittingly perpetuate practices that exclude disabled people.

It might be worth noting that if your church service disintegrates when you cut out saying “lame” as a slur, you aren’t worshiping God in the first place. If you’re worried that spending money on a ramp or elevator isn’t worth it, you probably aren’t as welcoming to disabled people as you think. If you have concert lighting but don’t have an accessible bathroom, you might have lost the plot of what church is a long time ago.